This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

The American Black Duck has pulled off a feat most waterfowl wouldn’t dare attempt—it winters farther north than nearly any other dabbling duck, thriving in frozen marshes where ice forms on coastal waters. This hardy species, scientifically known as Anas rubripes, has carved out its niche along eastern North America’s rugged coastlines and wooded wetlands, adapting to environments that push other ducks south.

You’ll recognize it by its dark chocolate plumage and violet-blue wing speculum, though it’s often mistaken for its close relative, the Mallard. Despite a 60 percent population crash between the 1960s and 1990s, this resilient bird continues to navigate threats from habitat loss to genetic blending with Mallards.

Understanding what makes this duck unique—from its physical traits to its conservation challenges—reveals why protecting it matters for wetland ecosystems across the Atlantic Flyway.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What is The American Black Duck?

- Distinctive Physical Characteristics

- Habitat and Geographic Range

- Behavior and Feeding Habits

- Differences From Similar Duck Species

- Conservation Status and Protection Efforts

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- How to identify an American black duck?

- Where do American Black Ducks live?

- Can you hunt American Black Ducks?

- What is the American black duck?

- How big is an American black duck?

- Are black ducks common in North America?

- What is the scientific name of a black duck?

- How many black ducks are there?

- Are black ducks dabbling ducks?

- Where do American black ducks live?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- The American Black Duck winters farther north than nearly any dabbling duck, thriving in frozen coastal marshes where most species retreat south, though its population crashed 60 percent between the 1960s and 1990s due to overhunting and habitat loss.

- You’ll identify this chocolate-brown duck by its violet-blue wing speculum edged in black, pale head, and yellow-olive bill—but genetic swamping from Mallard hybridization threatens to erase its distinct bloodline across overlapping territories.

- This species adapts to both freshwater wetlands and saltwater marshes through specialized salt glands and thermal tolerance, shifting its diet seasonally from aquatic plants and invertebrates in spring to coastal mussels and agricultural grain during migration.

- Conservation efforts have stabilized populations since the 1980s, but habitat conversion from urban sprawl, climate-driven saltwater intrusion, and continued Mallard competition demand ongoing wetland restoration and protection across the Atlantic Flyway.

What is The American Black Duck?

The American Black Duck is a hardy waterfowl species that thrives in eastern North America’s coastal wetlands and wooded waterways. This close relative of the Mallard has adapted to some of the continent’s harshest environments, wintering farther north than most dabbling ducks.

In Delaware’s coastal marshes, they frequently interbreed with Mallards, creating hybrid ducks that challenge identification for even experienced birders.

Understanding its scientific background and relationship to other species reveals why this dark-bodied duck stands apart from its more common cousins.

Scientific Name and Classification

You’ll find the American Black Duck classified under the binomial nomenclature Anas rubripes, a scientific name that precisely identifies this species worldwide. This taxonomic hierarchy places it within the Anatidae family alongside other waterfowl:

- Class Aves anchors it among all birds

- Order Anseriformes groups it with ducks and geese

- Genus Anas connects it to dabbling ducks

- Species rubripes distinguishes this unique duck from its relatives

Relationship to Mallards

You’ll notice the American Black Duck shares the genus Anas with Mallards—both dabbling duck cousins within the same family tree. This habitat overlap creates intense competition dynamics for nesting sites and food resources.

Genetic swamping threatens Black Duck populations where Mallards expand their range, producing hybrids that dilute pure bloodlines. Behavioral influence from Mallards has reshaped waterfowl conservation strategies across overlapping territories.

Distinctive Physical Characteristics

You can’t properly identify an American Black Duck if you don’t know what to look for. This species carries a set of physical traits that set it apart from other waterfowl, even its close cousin the Mallard.

Here’s what makes this duck unmistakable in the field.

Size, Weight, and Wingspan

You’re looking at a sturdy waterfowl that stretches 23 to 26 inches from bill to tail, tipping the scales at roughly 1.8 to 2.6 pounds. The American Black Duck’s wingspan sweeps 36 to 40 inches, giving it the lift it needs for long migrations.

Body proportions favor a broad chest for buoyancy, while feather density shifts with the seasons to keep this duck species primed for survival.

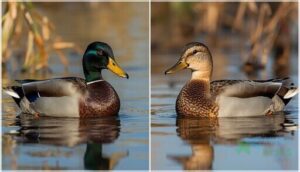

Male Vs. Female Appearance

Spotting the difference between male and female American Black Ducks takes a sharp eye, but you’ll pick up the clues once you know where to focus.

- Head colors: Males show darker, glossier heads with a greenish sheen; females display duller, brownish tones.

- Bill shapes and hues: Males sport deeper, uniform bill colors; females reveal lighter, mottled patterns.

- Plumage patterns: Males wear sleek, uniform feathers; females exhibit matte, speckled textures.

- Size differences: Males carry broader chests and slightly longer wings.

- Feather textures: Males appear glossy; females blend with wetland backgrounds through streaked, less reflective plumage.

Unique Plumage and Markings

You’ll recognize the American Black Duck by its rich, dark chocolate brown plumage that shifts from blackish to purplish in sunlight—an iridescence effect few bird species match.

Its deep plumage sets it apart from the black birds with red chest you might find in similar wetland habitats.

The violet-blue wing speculum, bordered with black and white, catches your eye during preening. Watch for the pale blue-gray secondary feathers creating subtle banding patterns, and you’ve nailed this distinctive species.

Identifying Features in Flight

When you catch this bird species identification in flight, watch for the broad, rounded wing shapes that power steady, rhythmic wingbeats. The dark body contrasts sharply with white underwing coverts—your best visual cue.

Flight patterns include shallow glides between flaps, and that violet-blue speculum flashes during turns. Flight speed stays moderate, with aerodynamic features supporting level flight during avian migration patterns across wetlands.

Habitat and Geographic Range

The American Black Duck doesn’t follow the crowd regarding where it lives. You’ll find this hardy bird in a range of habitats that stretch from the Atlantic Coast deep into eastern Canada, thriving in both freshwater marshes and salty coastal waters where other dabbling ducks won’t venture.

Here’s where you can track them down across their North American range.

Native Range in North America

You’ll find the American Black Duck carving out its territory across eastern North America, from the rugged Atlantic Breeding grounds in eastern Canada down through the Great Lakes Inland wetlands.

These hardy waterfowl follow the Atlantic Flyway south each fall, trading northern marshes for Gulf Wintering sites along coastal marshes.

Their Migration Corridors span the continent’s eastern edge, connecting breeding and wintering worlds.

Preferred Habitats (Freshwater, Saltwater, Coastal)

Think of American Black Ducks as wetland nomads—they’ll settle wherever freshwater wetlands, saltwater marshes, and coastal ecosystems converge. You’ll spot them thriving in five key ecological habitats:

- Inland ponds with soft bottoms and aquatic vegetation

- Tidal flats offering invertebrate-rich foraging at low tide

- Brackish zones where fresh and saltwater mix

- Coastal marshes providing protected roosting sites

- Wetland ecosystems from agricultural ponds to natural estuaries

These birds adapt to both coasts and shorelines with striking flexibility.

Seasonal Migration Patterns

American Black Duck migration unfolds along coastal and estuarine flyways, where you’ll witness birds traveling between northern breeding zones and southern wintering grounds as temperatures drop and daylight shrinks.

Most populations depart after first hard frosts freeze open water, returning when spring thaw signals ice-out. Climate impacts now shift waterfowl migration patterns—warmer winters keep some birds resident year-round rather than following traditional duck migration stopover sites.

Key migration behaviors are shaped by varied environmental factors, which can affect routes and timing each season.

Adaptations to Different Environments

You’ll find the American Black Duck thrives where other waterfowl struggle, thanks to exceptional environmental adaptability that spans freshwater ponds, brackish estuaries, and salt marshes. Their survival strategies include:

- Thermal tolerance through insulating plumage during frigid northern winters

- Habitat flexibility exploiting variable wetland extent year-to-year

- Salt gland adaptations enabling saline intake excretion in coastal ecological habitats

This ecological niche keeps them resilient across wetland ecosystems. The ability of black ducks to adapt is a prime example of in response to changing environments.

Behavior and Feeding Habits

American Black Ducks don’t follow the same playbook as other waterfowl—they’ve carved out their own feeding niche in both fresh and saltwater environments. You’ll find them tipping upside-down in shallow water, grazing along mudflats, and occasionally venturing into crop fields when the opportunity strikes.

Understanding how these ducks feed, nest, and interact with each other reveals why they’ve managed to thrive in tidewater habitats where other dabbling ducks struggle.

Dabbling and Foraging Techniques

You’ll spot these hardy waterfowl using classic dabbling techniques—tipping forward with tails skyward to reach vegetation just below the surface. They forage in shallow water less than 18 inches deep, their bills filtering aquatic plants and invertebrates from mud. Unlike deep divers, American Black Ducks keep their eyes above water while feeding, staying alert to danger.

Their feeding behaviors shift with habitat—coastal birds disturb sediment in brackish marshes while inland populations work beaver ponds and freshwater wetlands.

| Foraging Strategy | What It Targets |

|---|---|

| Surface feeding | Algae, floating seeds, small prey near water’s edge |

| Shoreline probing | Worms, snails, invertebrates hidden in soft mud |

| Up-ending dabs | Submerged vegetation, roots, aquatic insects |

| Group foraging | Vegetation-rich zones with increased feeding efficiency |

Typical Diet by Season and Location

What your black duck consumes shifts dramatically with the calendar and geography. Spring sees them loading up on aquatic plants and invertebrates in freshwater zones, while coastal populations rely heavily on mussels and crustaceans during harsh winters. Fall migration nutrition comes from agricultural fields—spilled corn and soybeans fuel their journeys south.

Seasonal foraging patterns reveal adaptive genius:

- Summer brings pondweed seeds and midge larvae during nesting

- Autumn shifts to post-harvest grains for fattening

- Winter coastal diet emphasizes marsh grasses and bivalves

- Northern birds exploit longer ice-free periods for plant foods

Nesting and Brood Rearing

Your female will nest within 100 to 400 meters of water’s edge, tucking eggs into dense vegetation that shields the brood from predators. She incubates 8 to 12 eggs for roughly 24 to 28 days, then leads ducklings through shallow wetlands rich in invertebrates.

Habitat fragmentation threatens this delicate choreography—broken landscapes force longer, riskier journeys between nesting sites and feeding zones.

Social Behavior and Flocking

Once your ducklings fledge, they join small to medium flocks that demonstrate collective defense and social learning through shared vigilance. Group foraging spreads birds across productive patches while migration patterns intensify flock dynamics at stopover sites. Visual signals and vocal exchanges coordinate spacing, enabling rapid alignment when threats emerge.

This avian behavior mirrors survival strategies seen across dabbling duck species traversing unpredictable wetlands.

Differences From Similar Duck Species

You’ll often see American Black Ducks in the same places as Mallards, and telling them apart takes practice. These species share enough traits that they regularly interbreed, creating hybrids that complicate identification even further.

Here’s what you need to watch for when sorting out these look-alikes in the field.

Comparison With Mallards

You’ll notice the American Black Duck and Mallard share duck behavior and habitat overlap, but there’s no mistaking them once you know what to look for. Mallards flash that bold green head and white neck ring—males, anyway—while your Black Duck stays uniformly dark brown.

Feather coloration differs dramatically: Mallards sport bright blue speculums with white borders, contrasting sharply with the Black Duck’s subtle violet patch. Beak shapes and body weight favor the heavier, longer-billed American Black Duck.

Hybridization and Its Impact

Genetic mixing between American Black Ducks and Mallards creates hybrid zones where species blending threatens population integrity. Introgression effects ripple through duck behavior and conservation genetics—hybrids carrying Mallard genes can dilute the Black Duck’s unique adaptations.

Ornithology research shows this hybridization accelerates when habitats shift, pushing distinct populations together and eroding the wild character that once defined eastern wetlands.

Key Identification Tips for Birders

You’ll nail American Black Duck identification by zeroing in on field marks that matter—dark chocolate plumage patterns, a slate-gray bill that breaks from mallard orange, and that violet-blue wing speculum edged in black.

Watch for steady wing beats in flight and note how bill shapes contrast with similar species.

Master these feather colors and you’ll claim freedom from ID confusion in the field.

Conservation Status and Protection Efforts

The American Black Duck faces real pressure from shrinking wetlands and competition with Mallards. Understanding its conservation status helps you see why protecting this species matters.

Here’s what you need to know about population trends, threats, and how conservation efforts are working to turn things around.

Population Trends and Threats

American Black Duck populations took a nosedive—down 60 percent from the 1960s to the 1990s—thanks to overhunting and habitat conversion. Though conservation efforts and legal protections stabilized numbers, you’re still looking at populations well below historical highs.

American Black Duck populations plummeted 60 percent between the 1960s and 1990s due to overhunting and habitat loss, stabilizing only after conservation intervention

Hybridization risks with Mallards add genetic pressure, while harvest regulations and ongoing conservation strategies work to reverse the decline. The IUCN status remains “Least Concern,” but regional losses tell a different story.

Habitat Loss and Climate Change Impacts

You’re witnessing habitat conversion slice through wetland ecosystems at alarming rates—urban sprawl and agricultural drains fragment the marshes Black Ducks depend on. Climate shifts drive coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion, while ecosystem disruption from warming winters desynchronizes migration with food availability.

Wetland degradation strips away foraging grounds, making habitat restoration and biodiversity protection essential for ecological sustainability.

Conservation Programs and Research

You’ll find federal wildlife agencies funding habitat restoration projects that rebuild wetlands and native vegetation across critical stopover sites. Climate research pinpoints where restoration delivers maximum impact under future scenarios, while conservation funding secures breeding and wintering areas.

Wildlife partnerships coordinate ecosystem management through state, local, and nonprofit teams tackling regional protection. Ornithological research and waterfowl conservation strategies drive American Black Duck conservation through population monitoring networks tracking numbers and distribution to inform wildlife conservation efforts.

How to Support American Black Duck Conservation

You can join the fight for American Black Duck conservation by backing wetland preservation and habitat restoration projects in your region.

Support conservation policy through advocacy, participate in community engagement through citizen science surveys, and champion sustainable practices that protect coastal marshes.

Your involvement in waterfowl conservation and wildlife conservation efforts strengthens avian ecology and conservation networks vital for this species’ survival.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How to identify an American black duck?

You’ll spot this ducklike bird by its shockingly dark chocolate-brown plumage, pale gray head, violet-blue wing speculum edged in black, and yellow-olive beak—ornithology’s clearest species identification markers for American black duck recognition.

Where do American Black Ducks live?

You’ll discover these ducks across eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, thriving in Coastal Habitats like Salt Marshes and Freshwater Wetlands.

Their Breeding Grounds span Lakes and wildlife habitats where Migration Patterns bring seasonal movement along the Atlantic seaboard.

Can you hunt American Black Ducks?

Yes, you can hunt American Black Ducks during designated waterfowl harvest seasons. USFWS and state wildlife agencies set specific bag limits and licensing requirements to balance hunting with conservation efforts protecting this species.

What is the American black duck?

You’ll find this chocolate-toned wanderer slipping through eastern marshes like a shadow—the American Black Duck (Anas rubripes), a large dabbling waterfowl whose dark plumage and violet speculum set it apart from brighter cousins.

How big is an American black duck?

You’ll find this waterfowl measures 21 to 23 inches long with a wingspan of 35 to 37 inches. Weight range runs from 6 to 6 pounds, with males outweighing females noticeably.

Are black ducks common in North America?

Black Duck populations have declined sharply across North America due to habitat loss and mallard hybridization. You’ll find them mainly in Eastern Canada and northeastern wetlands, though they’re far less common than decades ago.

What is the scientific name of a black duck?

You might think “black duck” tells the whole story, but ornithology research reveals the scientific classification holds deeper meaning.

The American Black Duck’s binomial nomenclature is Anas rubripes, where etymological analysis shows “rubripes” means red-footed.

How many black ducks are there?

You’ll spot a few hundred thousand American black ducks wintering along the Atlantic flyway—far below mid-century peaks.

Population trends show stabilization since the 1980s, though habitat loss and species decline continue threatening recovery.

Are black ducks dabbling ducks?

Yes, you’ll recognize American Black Ducks as dabbling ducks—tipping tail-up, tail-up, tail-up in shallow water.

They forage at the surface like mallards, never diving deep, catching aquatic plants and invertebrates with classic waterfowl techniques.

Where do American black ducks live?

You’ll find these ducks thriving along the Atlantic coast from Quebec to Virginia, favoring coastal habitats and freshwater wetlands like lakes, ponds, and marshes.

Migration patterns shift them between northern breeding grounds and southern wintering areas.

Conclusion

Think of the American black duck as a guardian standing watch at the frozen edge—while others retreat, it holds the line. Your efforts to protect coastal wetlands, support conservation programs, and advocate for habitat restoration directly determine whether this species survives or fades into genetic obscurity.

The marshes won’t defend themselves. Neither will the ducks. That responsibility falls to those who understand what’s at stake and refuse to look away.