This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

Over half of North America’s Black Swifts have vanished in just 50 years, making this dark, powerful bird one of the continent’s fastest-declining species. You might mistake it for a swallow at first glance, but the Black Swift belongs to a completely different family—Apodidae—and lives a life far more mysterious than its familiar cousins.

Over half of North America’s Black Swifts have vanished in just 50 years, making this dark, powerful bird one of the continent’s fastest-declining species. You might mistake it for a swallow at first glance, but the Black Swift belongs to a completely different family—Apodidae—and lives a life far more mysterious than its familiar cousins.

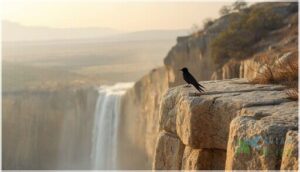

These aerial acrobats spend most of their time thousands of feet above ground, hunting insects at speeds exceeding 40 kilometers per hour, only returning to earth to nest behind thundering waterfalls or in sea caves. Their scientific name, Cypseloides niger, reflects their sooty plumage and resemblance to the swift genus Cypselus.

Understanding what makes Black Swifts unique—from their sickle-shaped wings to their extreme habitat preferences—reveals why protecting them requires urgent action.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What is a Black Swift?

- Physical Characteristics of Black Swifts

- Black Swift Habitat and Distribution

- Diet and Foraging Behavior

- Conservation Status and Threats

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is a black swift?

- What does a black swift look like?

- Where do black swifts live?

- What genus is a black swift?

- Where did black swift come from?

- Where do black swift roost?

- Do black swifts migrate?

- What do black swifts eat?

- What is the difference between a black swift and a Vaux’s swift?

- What is the status of the Black Swift?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Black Swifts have lost over half their North American population in 50 years, with some regions showing a devastating 92% decline since 1970, making them one of the continent’s fastest-disappearing bird species.

- These birds live almost entirely in the air at altitudes up to 13,000 feet and nest exclusively in extreme locations like cliff faces behind waterfalls or inside sea caves, requiring cool, moist conditions that climate change is rapidly eliminating.

- Black Swifts migrate over 7,000 kilometers from western North America to Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, spending more than 99% of their time airborne during non-breeding months while catching flying insects at speeds exceeding 40 kilometers per hour.

- Their decline stems from multiple threats including disappearing glacier-fed waterfalls due to climate change, habitat destruction in Amazon wintering grounds, reduced insect populations from pesticides, and human disturbance at nesting sites.

What is a Black Swift?

The Black Swift is North America’s largest swift, a dark, powerful flier that spends most of its life on the wing. You’ll rarely spot one sitting still since these birds hunt insects high in the sky and nest in hard-to-reach spots behind waterfalls.

Let’s look at how scientists classify this fascinating species and how its name has changed over time.

Scientific Classification and Naming

The Black Swift carries the scientific name Cypseloides niger, a label that’s stuck since Johann Friedrich Gmelin first described it in 1789. You’ll find it classified in the family Apodidae and order Apodiformes. The genus name Cypseloides combines “Cypselus” with a Greek suffix meaning “resembling,” while “niger” means “black” in Latin.

Black Swift Taxonomy highlights you should know:

- Originally misclassified as Hirundo nigra alongside swallows

- Reassigned to Genus Cypseloides by Philip L. Sclater in 1865

- Underwent multiple taxonomic revisions through the 20th century

- Classification hierarchy places it firmly in Kingdom Animalia, Class Aves

- Scientific references now consistently use Cypseloides niger across authoritative sources

This naming history reflects how ornithologists gradually understood swift relationships better, separating them from swallows and establishing clear taxonomic information through scientific synonyms and careful study. These birds are known to fly at remarkably high altitudes, making them difficult to spot.

Recognized Subspecies

You’ll find three recognized subspecies in Black Swift Taxonomy: Cypseloides niger borealis (southeast Alaska to southwestern United States), costaricensis (central Mexico through Costa Rica), and niger (West Indies and Trinidad). Borealis identification relies on geographic location since Niger characteristics overlap considerably across forms.

Scientific References show no documented Subspecies interbreeding, supporting Taxonomic validity. The Scientific Name Cypseloides niger applies to all three, with Taxonomic Information distinguishing them primarily by Costaricensis range boundaries.

These birds are known to breed in western North America.

Taxonomic History and Changes

Since Johann Friedrich Gmelin established the species name in 1789, you’ve seen significant taxonomy shifts in Black Swift classification. Genus Evolution stabilized when August Vollrath created Cypseloides in 1848, separating it from Cypselus.

Subspecies Revisions followed through the 1950s-1970s using physical traits for avian identification.

Molecular Impact changed everything after 2000, as genetic data resolved Naming Disputes and altered Criteria Changes for species classification.

Physical Characteristics of Black Swifts

If you spot a Black Swift overhead, you’ll notice right away that it’s built differently than most birds. From its body size to the shape of its wings, every feature plays a role in how it lives and flies.

Let’s break down what makes this bird so distinctive.

Size and Measurements

You’ll find that Black Swifts pack impressive dimensions into their aerial frames. Wingspan variation reaches up to 18 inches, while weight fluctuation ranges between 1.4 and 1.9 ounces. Juvenile size mirrors adults closely.

Consider these measurement highlights:

- Length spans 7 to 7.25 inches, roughly robin-sized

- Wings stretch broad and curved for high-speed flight

- Tail morphology shows a distinctive notched profile

This size comparison confirms them as North America’s largest swift species.

Plumage and Coloration

You’ll notice that Black Swifts wear mostly blackish plumage with a subtle bluish gloss on their backs, showcasing feather iridescence from structural coloration. Adults display a frosty white forehead in flight, while juveniles sport more prominent pale edging.

Plumage variation between sexes is minimal, though females sometimes show whiter belly feathers.

Nestling down covers young birds completely, providing insulation in damp cliff nests.

Geographic differences remain subtle across populations.

Wing and Tail Structure

With wings spanning up to 18 inches, you’ll spot the Black Swift’s sickleshaped wings and notched tail creating remarkable wing aerodynamics. The pointed, crescent-shaped wings deliver flight efficiency through high aspect ratios, while skeletal adaptations support sustained gliding.

Stiff wingbeats and precise feather arrangement enable tail maneuverability around waterfalls. These structural features give you energy-efficient flight at high altitudes.

Distinctive Flight Pattern

You’ll recognize the Black Swift’s distinctive flight by its stiff wingbeats and high-speed aerial chases, reaching speeds near 69 mph. These sickleshaped wings support exceptional aerial endurance—over 99% of their time airborne during non-breeding months.

Watch them employ specialized foraging strategies while catching flying insects through rapid, undulatory paths. Their aerodynamic adaptations and migratory dynamics enable sustained flights at altitudes up to 13,000 feet.

Black Swift Habitat and Distribution

If you want to find a Black Swift, you’ll need to know where these special birds call home. Their range across North America is surprisingly specific, shaped by unique nesting needs that set them apart from other swifts.

Let’s explore where these high-flying hunters live, from their breeding grounds to their winter retreats.

Geographic Range in North America

You’ll find Black Swifts across western North America, from southeastern Alaska down to Costa Rica. Their breeding distribution spans a surprisingly large area, yet their local occurrence remains uncommon. Population estimates hover around 170,000 to 210,000 individuals. When winter arrives, they head to South America and the Caribbean—their wintering grounds include western Brazil.

Here’s where you might spot them across North America:

- British Columbia and Southeast Alaska – Remote cliff areas and mountainous regions

- Rocky Mountain States – Montana, Idaho, Colorado, and Wyoming

- Pacific Coast – California and Nevada, from sea level to high elevations

- Central America – Extending south through Mexico to Costa Rica

The Black Swift’s range shows considerable habitat diversity. They adapt to arroyos, canyons, coastal shorelines, forests, and high mountains. Their distribution across this geographic location reflects their need for rugged, remote environments with steep cliffs and waterfalls.

Specific Nesting Requirements

You’ll discover Black Swift nesting sites in some of nature’s most dramatic cliff locations—over 98% are tucked behind waterfalls or within sea caves.

These birds need cool, moist conditions for nest construction, building entirely from moss on vertical rock faces. Microclimate stability matters: temperatures around 9–20°C with high humidity.

Substrate composition, water exposure, and predator avoidance shape where they’ll build their single-egg nest.

Preferred Elevational Zones

Black Swift habitat spans mountainous regions from sea level to over 13,000 feet during altitude migration. You’ll usually spot nesting sites between 1,000 and 8,000 feet where waterfalls and cliffs meet their habitat requirements.

Foraging altitude shifts with weather—they’ll hunt insects higher up on clear days.

Climate impact affects these elevational zones, as warming temperatures alter Black Swift distribution and their preferred nesting elevation across North America.

Migration Patterns and Wintering Areas

Once these birds leave their cliff-side homes, you’ll find they’re true long-distance champions. Black Swift migration patterns take them roughly 7,000 kilometers from North American breeding sites to Brazil’s lowland rainforests. Migration timing runs late August through early September, with spring returns in late May.

During migration, they face serious challenges:

- Weather anomalies can delay departure and reduce insect prey

- Climate change creates mismatches between arrival and food availability

- Extreme storms increase mortality risks during flight

- Habitat destruction along routes reduces critical stopover sites

Tracking methods using lightweight geolocators have revealed their winter range spans the Amazon basin, with some birds wintering in Colombia and Venezuela. Environmental factors like prevailing winds affect their bird migration speed—they’ll cover about 211 miles daily in fall and 244 miles in spring. These wintering areas provide the insects they need year-round.

Diet and Foraging Behavior

Black Swifts are skilled hunters that catch all their food while flying through the air. Their diet changes throughout the year, and they often work together when they find a good food source.

Let’s look at what these birds eat, how they hunt, and the way their feeding habits shift with the seasons.

Types of Insects Consumed

As aerial hunters, Black Swifts have a diverse insect diet that shifts with the seasons. You’ll find them catching flying insects like flies, beetles, wasps, mayflies, and caddisflies.

Winged ants dominate their meals in late summer—these insects pack serious ant nutritional value with roughly 40% fat content. Early summer sees fly prey dominance, while beetle consumption rates stay consistent year-round across their range.

Foraging Techniques and Strategies

When catching their insect diet, you’ll see these birds use some impressive techniques. They hunt at altitudes where swarming prey gathers—sometimes over 700 meters high—scooping insects mid-flight with wide bills.

Here’s how their bird foraging habits work:

- Foraging Flight Speed exceeds 40 kilometers per hour during pursuit

- Aerial Prey Capture happens every 3 seconds during active feeding

- Water Source Foraging includes drinking while skimming streams

- Insect Swarm Exploitation benefits from group hunting dynamics

Foraging Altitude Variation helps them adapt to weather changes.

Seasonal Shifts in Diet

Throughout the year, you’ll notice the Black Swift diet shifts with available aerial insects. In spring, Diptera like midges make up 31% of meals. Summer brings a feast—62% flying ants and termites dominate foraging. Come autumn, beetles surge to 29% as birds bulk up before migration. During winter in South America, tropical termites and ants comprise 53% of their intake.

Climate changes now disrupt these patterns, altering insect availability by three weeks.

Social Feeding Habits

You’ll often spot these birds hunting together in loose flocks, swooping through insect-rich air. Group foraging helps reduce predation risk while boosting prey selection success.

They coordinate through visual flight patterns—synchronized dives and sharp turns—rather than calls. When insect abundance peaks, feeding behavior intensifies.

Their diet focuses on aerial insects like midges and flying insects, with larger groups forming where prey concentrates.

Conservation Status and Threats

The Black Swift is in serious trouble. Over the last 50 years, more than half of these birds have disappeared from North America, earning them endangered status in Canada and a spot on conservation watch lists.

Let’s look at what’s driving their decline, what scientists are doing to help, and why protecting their unique habitats matters more than ever.

Population Trends and Declines

You’re witnessing a vulnerable species in freefall. Historic declines show Black Swift populations have dropped by up to 92% since 1970, with a staggering annual decline of 5.39%.

Black Swift populations have plummeted 92% since 1970, declining at a staggering 5.39% annually

Recent estimates place Canada’s breeding population between 6,780 and 25,240 birds. Regional trends reveal breeding occupancy at fewer than 20 confirmed nesting sites in British Columbia.

Future projections warn that climate change could push another 50% decline by 2033, making conservation status increasingly urgent.

Major Threats to Survival

When glacier-fed waterfalls dry up and insect swarms vanish, Black Swifts face an uphill battle. Population decline stems from multiple threats:

- Habitat Degradation: Logging, mining, and deforestation in Amazon wintering grounds destroy critical nesting areas

- Climate Impacts: Reduced snowpack and warmer temperatures shrink waterfall habitats and alter insect availability

- Human Disturbance: Recreational activities near nesting sites cause abandonment

- Food Scarcity: Pesticides and climate change threats to birds reduce aerial insect populations

These combined pressures have worsened the species’ conservation status.

Conservation Efforts and Research

You can help protect Black Swifts through conservation programs that track population trends and nesting sites. Montana Audubon’s ten-year monitoring effort and citizen science initiatives in British Columbia document active nests and population decline patterns. Genetic diversity research using blood samples assesses adaptability, while protection policies like Canada’s seasonal access restrictions minimize disturbance. Tracking studies revealed their 8,600-mile migration to Brazil, informing climate impacts research on glacier-fed waterfall habitats.

| Conservation Focus | Research Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Population Monitoring | Dawn/dusk surveys at waterfalls | 51 active Montana nests (2021) |

| Genetic Diversity | Blood and feather sampling | Gene flow assessment underway |

| Migration Tracking | Geolocators since 2009 | Brazil wintering grounds confirmed |

| Climate Impacts | Temperature data collection | 6% annual population decline |

| Citizen Science | Community nest reporting | 41 adults, 11 nests detected |

Importance of Habitat Protection

You’ll find that protecting Black Swift habitat means safeguarding the waterfall nesting sites and insect-rich foraging areas these birds depend on. Conservation Status reflects steep declines driven by Climate Threats like shrinking glaciers. Nesting Site Security and Foraging Habitat Extent determine Conservation Strategy Success:

- Seasonal closures shield breeding waterfalls from human disturbance

- Protected water sources maintain spray-dampened nest ledges

- Intact forests support Insect Population Health year-round

- Climate Change Impact monitoring guides adaptive management

- Community science tracks Black Swift habitat occupancy patterns

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a black swift?

You’re looking at North America’s largest swift—a sleek, dark bird built for life in the air.

Scientists call it Cypseloides niger, and this Apodidae family member has seen its share of naming evolution through taxonomic history.

What does a black swift look like?

You’ll notice the Black Swift looks like a shadow on the wing—almost entirely sooty dark gray with a distinctive frosty brow.

It’s robin-sized with long, sickle-shaped wings and a slightly notched tail.

Where do black swifts live?

You’ll find Black Swifts in mountainous western regions from Alaska to Costa Rica, nesting on cliff faces behind waterfalls.

Climate impacts and habitat fragmentation threaten their coastal habitats and waterfall dependence, affecting wintering ecology across their distribution.

What genus is a black swift?

You’ll encounter one of the most notable Cypseloides characteristics: this genus hosts eight to nine swift species across the Americas.

The Black Swift, Cypseloides niger, represents its most widespread member within Apodiformes.

Where did black swift come from?

The Black Swift’s ancestral breeding grounds trace back to tropical mountain ranges in Central and South America.

Its closest relatives in genus Cypseloides reveal evolutionary relationships spanning 10-15 million years of diversification.

Where do black swift roost?

Though they spend daylight hours soaring vast distances, black swifts return faithfully to shaded cliff nesting locations and sea caves behind waterfalls.

These sites offer roosting microclimates that stay cool and damp, creating the perfect environment for their overnight roost site fidelity.

Do black swifts migrate?

Yes, you’ll find these amazing birds migrate vast distances. Black Swifts travel over 6,900 kilometers from western North America to wintering grounds in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, maintaining flight nearly continuously throughout migration.

What do black swifts eat?

You’ll see these aerial insect foraging specialists catching winged ants, flies, and beetles mid-flight. Their diet shifts seasonally, with carpenter ants dominating late summer.

They hunt at remarkably high altitudes, often exceeding 8,500 feet.

What is the difference between a black swift and a Vaux’s swift?

Like comparing a raven to a sparrow, you’ll notice swift bird species differ dramatically.

Plumage comparison reveals Black Swift identification by larger size, darker coloration, and distinct vocal differences.

Habitat overlap occurs, though Vaux’s prefers forests over waterfalls.

What is the status of the Black Swift?

The Black Swift conservation status is endangered in Canada due to a 50% population decline since Climate change, habitat loss, and reduced insect prey drive these declines, requiring urgent recovery strategies.

Conclusion

Perhaps it’s fitting that a bird spending most of its life in the clouds has quietly slipped toward extinction while we’ve been too busy watching sparrows at our feeders. The black swift’s story isn’t just about waterfalls and mountain skies—it’s a mirror reflecting our collective blind spot for creatures that don’t pose for easy photographs.

Protecting what we barely see demands looking up more often, both literally and figuratively, before these dark silhouettes vanish completely.