This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

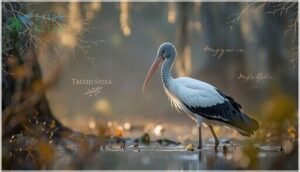

You can spot a Wood Stork from a distance by its unusual profile. The bare gray head and heavy black bill look almost prehistoric, and when it flies overhead with its neck stretched out and legs trailing behind, it cuts a distinctive shape against the sky. This large wading bird stands nearly four feet tall and is the only stork species native to North America.

Wood Storks spend their days probing shallow wetlands for fish, relying on touch rather than sight to catch prey with lightning-fast reflexes. Their survival depends on healthy wetlands with the right water levels at the right times.

Once on the brink of disappearance with only a few thousand pairs left, conservation efforts have helped their numbers recover, though they still face serious challenges from habitat loss and changing water patterns across their range.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Wood Stork Identification and Classification

- Wood Stork Habitat and Geographic Range

- Physical Adaptations and Flight Characteristics

- Feeding Behavior and Diet

- Breeding and Nesting Habits

- Conservation Status and Threats

- Role in Wetland Ecosystems

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- How rare is a wood stork?

- Where can wood storks be found?

- What does it mean if you see a wood stork?

- How many wood storks are left in Florida?

- How do wood storks interact with other bird species?

- Whats the average lifespan of a wood stork?

- Do wood storks migrate seasonally?

- How do climate changes affect wood stork populations?

- Are there any cultural significance to wood storks?

- What sounds do wood storks make?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Wood Storks are North America’s only native stork species and use a specialized tactile hunting method that snaps their bill shut in 25 milliseconds when prey touches it, making them entirely dependent on shallow wetlands with water depths between 2 and 15 inches.

- After dropping to fewer than 5,000 breeding pairs by 1984 due to wetland loss and water mismanagement, conservation efforts helped Wood Stork populations recover to over 10,000 breeding pairs by 2021, leading to their downlisting from endangered to threatened status in 2014.

- The species serves as a critical indicator of wetland ecosystem health because their breeding success directly reflects water management quality, prey fish abundance, and habitat conditions across southeastern wetlands.

- Climate change and ongoing water management challenges continue threatening Wood Storks through altered rainfall patterns, sea level rise, and disrupted hydroperiods that disperse prey fish during critical nesting periods, though the birds show adaptive behaviors like northward range expansion and increased use of urban wetlands.

Wood Stork Identification and Classification

If you’ve ever spotted a large white bird wading through southern wetlands with what looks like a bald gray head, you’ve likely seen a Wood Stork. This striking species is North America’s only native stork and belongs to the family Ciconiidae.

Let’s look at how you can identify these impressive waders and what sets them apart from other large water birds.

Scientific Name and Taxonomy

The wood stork carries the scientific name Mycteria americana, assigned by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. You’ll find it within the family Ciconiidae and genus Mycteria. This species identification separates it from all other North American wading birds. As an endangered species, conservation efforts are essential for its survival.

- Taxonomic history includes outdated naming synonyms like “wood ibis” and Tantalus loculator

- Phylogeny studies confirm its placement among early-diverging waterbird lineages

- Taxonomy shows it’s the sole Ciconiidae breeder in North America

Species characteristics in taxonomic information help you recognize authentic wood stork description.

Distinctive Physical Features

Once you know the scientific classification, you can spot this bird by its striking appearance. Adult wood stork identification depends on several key features. The bare gray head scalation contrasts sharply with white body plumage. Black flight feathers create a dramatic color pattern in flight. The long, thick bill curvature curves downward for specialized feeding. Long black leg coloration and pinkish toes complete the distinctive look. Given their appearance, a key aspect of identification is their distinctive bare heads.

Juvenile plumage shows buffy coloring on the head before changing to adult characteristics over one to four years. The flight silhouette—with neck outstretched and legs extending beyond the tail—helps with bird identification from a distance. These wood stork characteristics make field recognition straightforward once you know what to look for in your wood stork description guide.

| Feature | Adult | Juvenile |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Bald, gray, scaly | Dusky, feathered |

| Bill Curvature | Black, downcurved | Yellow-orange |

| Plumage | Pure white body | Pale buff-tinged |

| Leg Coloration | Black with pink toes | Slightly lighter |

| Flight Silhouette | Neck extended, legs trailing | Similar posture |

Size, Shape, and Measurements

Understanding these physical characteristics helps you appreciate the size and shape of this large wading bird. Wood Stork measurements show adults standing 33 to 45 inches tall with a wingspan of 59 to 68 inches. Weight fluctuation ranges from 4.4 to 7.3 pounds. Sexual dimorphism appears in body proportions—males have longer bills and leg length than females.

- Adult height generally reaches 3 to 4 feet from head to tail

- Wingspan variation spans up to 5.5 feet for efficient soaring

- Males weigh slightly more with 9-inch bills versus females’ 7.9-inch bills

- Football-shaped body with extended neck creates unique flight silhouette

Differences Between Adults and Juveniles

You can spot age differences in wood storks by checking the head and bill. Immature birds have yellowish bills and feathered necks during their first year. Young wood storks gradually lose these feathers, developing bare, scaly gray skin by age four.

Chicks start with gray down that turns white within 10 days. Plumage development continues for years, with survival rates climbing from 31% in year one to 75% by year three.

Wood Stork Habitat and Geographic Range

Wood storks don’t just pick any body of water to call home. They need specific wetland conditions to survive and thrive.

Let’s look at where you’ll find these birds across their range and how they move with the seasons.

Preferred Wetland Ecosystems

You’ll find wood storks where water levels tell the story of survival. These birds depend on specific wetlands like cypress swamps and southern swamps, where the wetland hydroperiod—the wet-dry cycle—concentrates prey in shallow pools.

Their ecosystem dependence is absolute, shaping every choice:

- Foraging vegetation: Open canopy wetlands beat dense forests for catching fish

- Nesting structures: Trees over standing water protect chicks from predators like raccoons

- Water depth: Shallow zones of 2-15 inches improve feeding success

- Geographic expansion: Habitat loss pushes populations into new southeastern wetlands

Distribution in The United States

Across the southeastern United States, you’ll track wood stork breeding range shifts from Florida north into Georgia, South Carolina, and southeastern North Carolina. The breeding range concentrates along the coastal plain, where conservation status improvements reflect restoration program impact.

Colony location changes show more than 70 active sites by 2002, up from 29 in 1984. Urban-adjacent residency patterns now supplement traditional strongholds, reshaping population density maps and geographic distribution.

Range Across Central and South America

Beyond U.S. borders, you’ll encounter wood stork populations spanning from Mexico through Panama into northern Argentina. Habitat connectivity remains strong across these wetland strongholds, though conservation challenges persist.

Regional declines threaten:

- Colombian and Ecuadorian floodplains affected by river alteration

- Central American wetlands facing agricultural conversion

- Brazil’s Pantanal colonies impacted by water regulation

- Population genetics showing minimal divergence despite geographic distribution gaps

Conservation status monitoring reveals ongoing habitat pressures across the range.

Seasonal Migration Patterns

You’ll notice wood stork migration patterns reveal surprising flexibility. About 59% migrate seasonally between Florida winters and northern summer ranges, while 28% stay put year-round near urban Florida habitats. Another 13% switch strategies depending on conditions.

These movements respond to food availability and wetland cycles. Dispersal distances stretch from 330 to over 530 miles. Understanding these migration triggers and habitat connectivity proves essential for conservation planning across their range.

Physical Adaptations and Flight Characteristics

The Wood Stork’s body is built for life in shallow wetlands. Every feature, from its heavy bill to its broad wings, has a specific purpose in finding food and traversing its watery world.

Let’s look at the key physical traits that make this bird such an effective wader and flier.

Bill Structure and Feeding Adaptations

The wood stork’s black bill is like a high-tech fishing rod built for touch. This long, decurved tool measures 25 to 30 cm and snaps shut in just 25 milliseconds when prey brushes against it.

The wood stork’s bill snaps shut in 25 milliseconds, functioning like a high-tech fishing rod built for touch-based hunting

You’ll find this tactile foraging technique works best in shallow, muddy waters where vision fails. The bill’s laterally compressed shape lets storks probe tight spots efficiently while hunting fish and other aquatic prey.

Wing Shape and Flight Patterns

Think of the wood stork as a sailplane with feathers. You’ll spot its broad wings stretching 150 to 175 cm across, riding thermals up to 2,000 feet without a single flap.

Those black flight feathers aren’t just for show—they’re part of aerodynamic adaptations that help these birds glide 15 miles at 12 mph while barely burning energy.

Plumage and Coloration Details

When you get close enough, you’ll notice the wood stork’s plumage tells a story. Adults wear crisp white bodies with greenish-black wing feathers showing subtle iridescence under sunlight. During breeding season, they flash pale salmon-pink underwings as courtship signals.

Juveniles look different—dingy gray plumage covers their feathered heads until year three or four, when dark scaled skin gradually replaces those feathers.

Visual identification markers you’ll see:

- Black flight feathers shimmer with purplish-green iridescence in bright light

- Breeding adults display salmon-pink coloring beneath wing coverts and on toes

- Juvenile plumage appears dingy white or tan-tinged with yellowish bills

- Dark gray scaled skin on bare heads resembles wrinkled leather texture

Feeding Behavior and Diet

Wood storks have a feeding method that’s different from most other wading birds. They don’t rely on sight to catch their prey.

Instead, they use a specialized hunting technique that depends on touch and timing to find food in murky waters.

Tactile Foraging Methods

Instead of relying on sight, you’ll find wood storks use an impressive Bill Snap Reflex for Prey Detection. Their feeding behavior involves submerging an open bill underwater and snapping it shut in just 0.25 milliseconds when prey species trigger mechanoreceptors.

This strike speed delivers remarkable foraging efficiency, with success rates exceeding 75% in shallow marshes.

Environmental influence, particularly water depth between 5-30 centimeters, directly affects wood stork behavior and diet through tactile foraging habits.

Primary Prey and Diet Diversity

Once that lightning-fast bill snaps shut, you might wonder what wood storks actually catch. Fish dominance drives their diet year-round, especially during dry months when fish like topminnows and sunfish make up nearly 100% of meals. Their foraging habits shift with seasonal variation, though:

- Crustacean consumption rises to 35% in wet season

- Amphibian diversity adds frogs and tadpoles opportunistically

- Mammal opportunism occurs during droughts

- Prey species average just 2 inches long

Influence of Water Levels on Feeding Success

Water levels are critical to the feeding success of wood storks. These birds thrive in water depths between 2 and 15 inches, where prey concentration is highest. As water recedes, fish become concentrated in shrinking pools, significantly increasing foraging efficiency. Conversely, rising water levels during nesting periods disperse fish, leading to higher nest abandonment rates. This strong connection between hydrological cycles and feeding success directly influences population dynamics and shapes habitat restoration efforts.

| Water Condition | Impact on Feeding |

|---|---|

| Receding levels (-1.5 to -4.8 cm/week) | Concentrates fish; increases foraging efficiency |

| Shallow water (2-15 inches) | Best prey concentration zone |

| Rising levels during breeding | Disperses fish; triggers nest abandonment |

| Stable hydroperiods | Encourages breeding synchronization |

Breeding and Nesting Habits

Wood storks are social nesters who rely on colony life to raise their young successfully. Their breeding season runs mainly from December to August across North America, though timing varies by location.

Understanding how these birds build nests, lay eggs, and care for their chicks gives you insight into what they need to thrive.

Colonial Nesting Sites

Wood storks are social birds that gather in breeding colonies, usually in wetland trees like cypress and mangroves. You’ll find nesting habitats ranging from 2.5 to 24 meters high, with up to 25 nests crowding a single tree.

Colony site selection depends on surrounding wetland quality and water levels. Habitat degradation impact threatens these nesting colonies, making conservation site management essential for population recovery strategies and nesting success factors.

Nest Construction and Materials

Both parents work together for 2 to 3 days building bulky platform nests from thick branches and finer twigs. Males travel farther to gather materials while females arrange them.

Material theft happens in breeding colonies as birds take sticks from neighbors. You’ll notice nests measure 1 to 1.5 meters wide and sit over water to prevent predation.

Wood storks don’t reuse nests due to deterioration.

Egg Laying and Incubation

After nest construction, females lay two to five creamy white eggs spaced one to two days apart. Clutch size depends on environmental triggers like water levels and food availability.

The incubation period lasts 27 to 32 days, with both parents sharing duties in roughly 96-minute shifts. Since egg laying is staggered, you’ll see a hatching sequence where the first eggs hatch days before the last.

Chick Development and Parental Roles

Once the eggs hatch, chick growth moves remarkably fast. Hatchlings weigh just 62 grams but reach half their adult height in three to four weeks. You’ll notice their beaks growing about 2.5 millimeters daily during early development.

Feeding frequency starts high, with parents delivering meals three to ten times per day. As chicks mature, parents increase trip frequency without extending absences. One breeding season demands roughly 201 kilograms of fish per family.

Key aspects of parental care:

- Both parents share feeding and nest attendance duties equally throughout chick-rearing

- Continuous parental guarding occurs during the first three weeks after hatching

- Chicks are brooded full-time for their first week, then at night or during rain

- Parents leave older chicks unattended once they reach three weeks old

- Fledging occurs at 60 to 65 days, though young return for feeding one to three weeks after

Mortality rates hit hardest early on. Only 31% of chicks survive their first year, improving to 59% in year two. The first two weeks prove most dangerous, with predation and nest failures causing significant losses.

Parental roles show little differentiation between males and females. Success hinges more on foraging trip frequency than duration or dual nest attendance. Peak parental effort directly correlates with higher fledgling survival, making their teamwork essential during the demanding incubation period and beyond.

Conservation Status and Threats

The wood stork has faced a rocky road in recent decades. Once common across the Southeast, its numbers dropped sharply before conservation efforts began turning things around.

Let’s look at where the species stands today and what challenges still threaten its survival.

Historical Population Trends

Over the past century, dramatic shifts in Wood Stork numbers have been observed. Early abundance in the 1930s saw 15,000–20,000 breeding pairs across the Southeast. However, a mid-century decline reduced this figure by 75% as wetlands vanished. The species was listed as endangered in 1984, with only 4,000–5,000 pairs remaining. Subsequently, a range expansion northward occurred, and recent trends show promise, with nest counts reaching 12,342 in 2021.

| Period | U.S. Breeding Pairs |

|---|---|

| 1930s | 15,000–20,000 |

| 1960 | ~10,000 |

| 1980 | 4,800 |

| 2002 | 8,985 nests |

| 2021 | 12,342 nests |

Current IUCN and Federal Status

You’ll find the Wood Stork classified as Least Concern by the IUCN today, reflecting its global stability. In the U.S., it’s protected under the Federal Endangered Species Act as Threatened since 2014.

Conservation actions have driven population recovery, prompting a 2023 delisting proposal. Even if delisted, your local Wood Storks remain safeguarded under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Clean Water Act.

Habitat Loss and Water Management Challenges

Habitat loss and water management challenges continue threatening your local Wood Storks despite federal protections. Wetland loss eliminated 35% of South Florida feeding areas since 1900, while water manipulation through canals and levees disrupts natural cycles. This habitat destruction drives nesting decline and reduces foraging success.

You can see the damage through:

- Populations dropping from 20,000 pairs in the 1930s to fewer than 6,040 by 1984

- Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary seeing repeated nesting failures since the 1970s

- Habitat fragmentation causing 80% of colony locations to shift within ten years

- Water not persisting long enough during dry season for chick survival

- Colony sizes shrinking as wetlands become increasingly disconnected

Water management challenges affect when fish concentrate in shallow pools, making prey inaccessible to breeding storks. Habitat fragmentation limits connectivity between your local nesting and foraging sites, creating unstable colonies across the Southeast.

Effects of Climate Change on Populations

Climate change impacts birds like Wood Storks through rising seas and shifting rainfall patterns. Migration shifts have been observed as temperatures push populations northward since the 1970s. Climate threats include habitat inundation—sea levels could rise 7 to 23 inches by 2100, drowning critical nesting sites.

| Climate Impact | Effect on Wood Storks |

|---|---|

| Sea Level Rise | Habitat inundation of Everglades nesting areas |

| Altered Rainfall | Disrupted breeding cycles reduce food availability |

| Temperature Increase | Migration shifts expand range northward |

Despite population decline in South Florida, adaptive behaviors help maintain population resilience. About 59% still migrate traditionally, while 28% have become year-round residents. Wood Stork conservation benefits from their dietary flexibility—they’re increasingly using urban wetlands and eating nonnative fish when natural prey becomes scarce.

Role in Wetland Ecosystems

Wood storks play a bigger role in wetlands than you might expect. These birds tell us a lot about the health of their ecosystems and respond quickly when things go wrong.

Understanding their place in wetlands helps explain why protecting them matters so much.

Indicator of Ecosystem Health

The Wood Stork acts as a wetland health indicator you can rely on. Its population trend analysis and breeding success rates reveal ecosystem restoration progress. When prey fish abundance drops, you’ll see fewer nesting pairs. The Wood Stork ecosystem role includes:

- Signaling water quality changes

- Reflecting fish population health

- Monitoring habitat degradation

- Guiding conservation priorities

- Tracking restoration effectiveness

Wood Stork habitat conditions tell you how well the ecosystem functions.

Impact of Wetland Changes on Wood Storks

Changes in wetlands have reshaped where and how successfully Wood Storks breed. Since the 1970s, you’ve seen their nesting shift northward as South Florida’s hydrology changed.

Altered water levels disrupt foraging behavior and reduce prey availability. Overdrainage shortens fish reproduction periods. These habitat degradation pressures represent major threats to breeding success.

Long-term trends show Wood Stork habitat quality matters more than quantity for Wood Stork conservation.

Conservation and Recovery Efforts

Through collaborative conservation programs, you’ve witnessed significant Wood Stork recovery since their 1984 endangered listing. Habitat restoration efforts, like wetland preservation and prescribed burns, increased nesting colonies from fewer than 16 to over 50.

Legal protection under federal laws secured critical habitat, while community engagement strengthened monitoring. These conservation efforts doubled breeding pairs to over 10,000, transforming threatened species outcomes across southeastern wetlands.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How rare is a wood stork?

Today, you’ll find over 10,000 breeding pairs across the southeastern United States. That’s an impressive comeback from the 1990s, when only half that many nested.

Their threatened species status reflects ongoing conservation needs despite recovery.

Where can wood storks be found?

You’ll spot them across southeastern wetlands from the Carolinas to Florida. Their breeding range stretches south through Central America and into South America.

Refuge habitats in coastal regions support key nesting colonies where wetland conservation fuels future expansion.

What does it mean if you see a wood stork?

Spotting a wading bird in wetland habitat can signal ecosystem health. For many cultures, stork sightings hold spiritual significance tied to fertility and new beginnings.

Their presence reflects successful wood stork conservation and ecological indicators.

How many wood storks are left in Florida?

Good news is sometimes hard to believe. Florida’s wood stork population has bounced back to over 10,000 nesting pairs today.

Habitat restoration and careful monitoring techniques helped this threatened species expand across 99 nesting colonies statewide.

How do wood storks interact with other bird species?

You’ll often see wood storks in mixed-species colonies alongside herons, egrets, and ibises. These wading birds share foraging areas and nesting sites.

They use visual cues from each other to find productive feeding grounds in wetlands.

Whats the average lifespan of a wood stork?

Wild lifespan for most wood storks ranges from 11 to 18 years. The oldest banded bird lived over 22 years. Captive longevity can exceed 27 years with proper care.

Do wood storks migrate seasonally?

Migration patterns in wood storks aren’t your classic north-to-south migration. Instead, you’ll see partial migration where about 59% of southeastern birds commute seasonally between Florida’s winter range and summer breeding areas, driven mostly by rainfall and food availability.

How do climate changes affect wood stork populations?

Climate change disrupts your wetland ecosystems through altered rainfall and rising seas. These hydrological shifts reduce prey availability and cause nest failures.

Range expansion northward shows adaptation strategies, though population decline risks remain without habitat restoration.

Are there any cultural significance to wood storks?

You’d think a silent, bald-headed bird wouldn’t inspire much poetry, yet wood stork symbolism runs deep.

Religious art, folklore connections, and cultural traditions reflect reverence for wetland guardians across conservation culture and indigenous heritage.

What sounds do wood storks make?

You’ll hear young wood storks making loud, nasal braying sounds and bill rattling in colonies.

Adults stay mostly silent except for low croaks, hissing, and bill clattering during breeding season interactions.

Conclusion

The wood stork’s story reads like a telegram from nature’s front lines—urgent, direct, impossible to ignore. These ancient waders remind us that wetlands aren’t just scenery. They’re life support systems.

When water management goes wrong, storks feel it first. Their recovery proves that targeted conservation works, but the work isn’t finished. Protecting the marshes and swamps they need means securing a future for countless species that share their world.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/TheFlaglerBeachPhotoClub/posts/7728055600627488/

- https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/wood_stork/status_study.html

- https://www.mexican-birds.org/wood-stork/

- https://www.dukevertices.org/blog/back-from-the-brink-wood-storks

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood_stork