This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

The sharp rat-a-tat-tat echoing through a Douglas fir forest isn’t just background noise—it’s a conversation you’re overhearing. Washington’s woodpeckers drum out territorial claims, courtship songs, and alarm calls across ecosystems ranging from rainforests to sagebrush steppes.

Eight distinct species carve out niches here, from the crow-sized Pileated that excavates cavities big enough to weaken entire trees, to the sparrow-sized Downy tapping at your suet feeder. Each species reveals something different about the landscape it inhabits.

The White-headed Woodpecker’s presence signals healthy ponderosa pine stands east of the Cascades, while the Red-breasted Sapsucker’s neat rows of sap wells mark the cooling forests of the western slopes. Learning to distinguish these birds opens up a new way of reading the forests around you.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Common Woodpecker Species in Washington

- Rare and Uncommon Washington Woodpeckers

- Identifying Woodpeckers by Appearance

- Woodpecker Habitats Across Washington

- Woodpecker Behaviors and Adaptations

- What Woodpeckers Eat in Washington

- Attracting Woodpeckers to Your Backyard

- Conservation Status of Washington Woodpeckers

- Woodpeckers’ Role in Forest Ecosystems

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- How many types of Woodpeckers are there in Washington State?

- Where do woodpeckers live in Washington?

- Are woodpeckers legal in Washington State?

- Are pileated woodpeckers common in Washington State?

- What do woodpeckers eat in Washington State?

- Are black backed woodpeckers common in Washington State?

- Are there woodpeckers in Washington State?

- What does a woodpecker look like in Washington State?

- Are white-headed woodpeckers common in Washington State?

- Are Lewis’s woodpeckers common in Washington State?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Washington hosts eight regular woodpecker species that function as ecosystem engineers—excavating cavities used by over 40 other species, controlling pest populations by up to 98%, and serving as reliable indicators of forest health across diverse habitats from rainforests to sagebrush steppes.

- Species like the White-headed and Lewis’s Woodpeckers face serious conservation challenges, with populations declining 48-72% due to habitat loss, fire suppression, and competition, while specialists require specific conditions like 26% old-growth coverage or post-fire landscapes to survive.

- You can identify woodpeckers by combining size (from 6-inch Downies to 19-inch Pileateds), bill length relative to head width, plumage patterns including sexual dimorphism in red markings, and distinctive drumming rhythms that range from 16 to 20+ beats per second depending on species.

- Attracting woodpeckers requires suet feeders, retaining dead snags when safe, maintaining at least 20% forest cover in suburban areas, and planting 70% native vegetation to support the insect populations that comprise 75-85% of most woodpecker diets year-round.

Common Woodpecker Species in Washington

Washington’s forests and backyards are home to a handful of woodpecker species you’ll spot most often. Each has its own quirks and favorite hangouts.

Here’s what you’ll want to know about the ones you’re most likely to see.

Downy Woodpecker

A classic among woodpecker species in Washington, the Downy Woodpecker’s tiny bill and spotted back make Woodpecker identification easy. You’ll spot these birds in Backyard Habitats and riparian woods, foraging for insects and seeds.

Subspecies Variations are common across the state. Their Nesting Habits and Diet Specifics support substantial Population Stability, even in changing Woodpecker habitats.

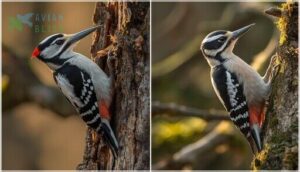

Hairy Woodpecker

If you’re scanning mature forests for Woodpeckers in Washington, the Hairy Woodpecker stands out—long, chisel-like bill, bold stripes, and a knack for nesting in big snags. You’ll notice their Diet Specificity: mostly beetle larvae and some fruit.

Habitat Fragmentation and Nesting Competition with starlings drive Population Decline, making Conservation Strategies and Woodpecker identification more important than ever.

Northern Flicker

If Hairy Woodpeckers are the forest’s chisels, Northern Flickers are the backyard acrobats. You’ll spot Urban Flickers hopping on lawns for ants—more than half their Flicker Diet is insects. For Flicker Identification, look for red mustache stripes and brown crowns. Their Nesting Habits favor dead trees, but:

- Adapt to parks and gardens

- Forage mainly on ground

- Create nest cavities

- Face Conservation Challenges

Pileated Woodpecker

If you’ve ever glimpsed a crow-sized shadow darting through Washington’s forests, you’ve met the Pileated Woodpecker. With its fiery red crest and booming calls, this keystone species shapes forest habitats and ranges by carving deep nest cavities.

You’ll even spot them in city parks—proof of their urban adaptation—though population decline still shadows their story, especially with changing forest management.

Red-breasted Sapsucker

Think of the Red-breasted Sapsucker as Washington’s “sap-well artist.” You’ll spot this sapsucker species drilling neat rows in coniferous forests, mostly in western Washington. Their brush-tipped tongues lap up sap, and nest site reuse is common. Population trends are stable, but conservation concerns linger with habitat loss. Identifying characteristics? Red head, white belly, and a fondness for mixed woods. They’re closely related to Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers.

- Sap-well drilling experts

- Nest site reuse behavior

- Western Washington stronghold

- Stable population trends

- Conservation concerns with forest loss

Rare and Uncommon Washington Woodpeckers

Some woodpeckers in Washington are much harder to spot than others. These rare and uncommon species each have their own story and quirks.

Here’s what you need to know about the ones you’re least likely to see.

Lewis’s Woodpecker

If you’ve never seen a Lewis’s Woodpecker, you’re not alone—this striking species has nearly vanished from Washington. Once common in burn areas and prairies, habitat loss and competition with European Starlings have pushed populations down 72% since 1970. They’re known for their acrobatic flight, catching insects mid-air. Conservation efforts now focus on preserving dead trees and managing ponderosa pine forests where these flycatcher-like foragers still hunt.

| Feature | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Green back, pink body, red face | Unique among woodpeckers |

| Habitat | Open ponderosa pine, cottonwood groves | Eastern Washington only |

| Foraging Behavior | Hawks flying insects mid-air | Rarely pecks trees |

| Nesting Habits | Reuses same cavity for years | 6-8 eggs per season |

| Population Decline | 72% loss (1970-2014) | Competition and habitat loss |

White-headed Woodpecker

You’ll rarely spot a White-headed Woodpecker in Washington—fewer than 100 birds occupy scattered ponderosa pine stands in the northeast. Their striking black-and-white plumage stands out against coniferous forests, where pine seed dependence and nesting snags define survival.

Forestry impacts have decimated old-growth habitat, making conservation strategies critical. Look for them in Leavenworth or Wenas Wildlife Area, where this woodpecker species clings to existence amid habitat specificity challenges.

Black-backed Woodpecker

You won’t find Black-backed Woodpeckers in typical coniferous forests—they’re post-fire habitat specialists thriving where flames recently swept through eastern Washington. This rare candidate species faces serious population threats from salvage logging that removes the charred snags they depend on.

Watch for their foraging behavior on burned trees:

- Scaling charred lodgepole pine at 17-foot heights

- Excavating beetle larvae from recently-killed snags

- Achieving 87% nest success in heavily-burned Idaho forests

Conservation status remains precarious despite impressive nest success rates.

American Three-toed Woodpecker

The American Three-toed Woodpecker haunts Washington’s high-elevation coniferous forests east of the Cascade crest, where you’ll spot them scaling bark off spruce and fir snags. Their habitat preferences lean heavily toward disturbed areas—windstorms, floods, and recent burns create perfect feeding grounds.

Diet specifics reveal an intense focus: beetle larvae comprise over 95% of their intake.

Population trends show stability across their 1.6-million-strong global range, though conservation challenges like fire suppression and salvage logging threaten local breeding habits in suitable woodpecker habitats.

Identifying Woodpeckers by Appearance

Getting a positive ID on woodpeckers comes down to noticing a few key features. You’ll want to look at how big the bird is, what its feathers and markings look like, and the shape of its bill and head.

Once you know what to watch for, telling these species apart becomes a lot easier.

Size and Shape

When you’re identifying woodpeckers in Washington, size and shape are your first clues. Downy Woodpeckers measure just 5.5–6.7 inches—about two-thirds the size of their look-alike cousin, the Hairy Woodpecker, which stretches 7–10 inches. Bill morphology matters too: Downys have short bills compared to head width, while Hairys sport bills nearly as long as their heads are wide.

Northern Flickers reach 11–14 inches, and the crow-sized Pileated Woodpecker tops out at 16–19 inches with impressive wingspans up to 29 inches.

Plumage and Markings

Once you’ve nailed down size, plumage and markings seal the deal. Look for sexual dimorphism—males often sport red patches females lack. The Northern Flicker’s red mustache stripe? That’s your guy. Pileated Woodpeckers flash that striking red crest, while Downys in western Washington show dingy tan where you’d expect white.

Regional differences and juvenile plumage add layers, but these identifying characteristics won’t steer you wrong:

- Black-and-white striped heads on Hairys and Downys

- Salmon-red underwings on Washington’s Northern Flickers

- Golden-yellow crowns on male Black-backed Woodpeckers

Bill Length and Head Features

Bill length variation offers quick woodpecker identification clues you can spot from across the yard. The Hairy’s chisel-like beak stretches nearly as long as its head—about 25–30 mm—while the Downy’s stubby bill measures just 10–14 mm, barely a third of head length.

These skull adaptations aren’t just for show: unequal beak mechanics absorb pecking forces up to 1200 g, protecting that tiny brain during thousands of daily strikes.

Woodpecker Habitats Across Washington

Woodpeckers in Washington don’t stick to just one type of habitat—they’ve adapted to everything from dense mountain forests to your neighborhood park. Where you find them depends largely on what they’re hunting for and what kind of trees they need for nesting and drumming.

Let’s look at the main habitats where you’re most likely to spot these birds across the state.

Deciduous and Coniferous Forests

In Washington’s forests, you’ll find woodpeckers partitioning habitat by tree type—Hairy Woodpeckers stick to coniferous forests while Downy Woodpeckers favor deciduous woods. Forest composition matters: western Washington’s Douglas-fir and hemlock support different species than eastern ponderosa pine forests.

Management impacts are real—75% of western forests show landscape change from logging, affecting habitat availability. These measurable characteristics help predict where you’ll spot specific woodpeckers.

Burned and Old-growth Areas

Beyond typical forest types, you’ll discover woodpeckers in burned forests and old-growth areas where snag density drives habitat quality. Black-backed Woodpeckers show 12.6 times higher occurrence in fire-killed forests, concentrating their post-fire nesting in recently burned sites.

Old-growth importance can’t be overstated—larger, decayed snags in mature coniferous forests provide essential cavity excavation opportunities. Forest recovery accelerates when woodpeckers introduce decay fungi through their nest cavities, supporting habitat management goals across Washington’s fire-prone regions.

Urban, Suburban, and Rural Locations

In Seattle’s city parks and beyond, you’ll notice habitat fragmentation reshaping species distribution dramatically. Urban adaptation varies—Downy Woodpeckers thrive in suburban backyards and urban parks with backyard feeders, while rural decline affects specialists like White-headed Woodpeckers as old-growth vanishes.

Pileated Woodpeckers persist in woodland habitats when forest patches retain 20% canopy cover across Washington State:

- Minimum 20% forest cover sustains breeding populations

- Larger parks consistently support more woodpeckers in Washington

- Home ranges exceed 300 hectares in fragmented landscapes

Woodpecker Behaviors and Adaptations

Woodpeckers aren’t just hammering away at trees randomly—they’ve evolved some pretty special strategies to find food, defend territory, and raise their young. From specialized foraging methods to their signature drumming patterns, these birds have adapted to life in ways that make them stand out in Washington’s forests.

Let’s look at the key behaviors that help woodpeckers thrive throughout the year.

Foraging and Feeding Techniques

Woodpeckers and insects go hand-in-hand—these birds are nature’s pest control specialists. Different species exhibit distinct feeding habits: Pileated Woodpeckers excavate massive rectangular holes to access carpenter ants, while Northern Flickers forage on the ground for beetles. Prey detection involves both visual searching and listening for larval movements beneath the bark. Red-breasted Sapsuckers drill organized wells to feed on tree sap, and during winter months when insects are scarce, their diets shift toward nuts and fruits.

| Foraging Method | Species Examples |

|---|---|

| Excavation of wood | Pileated, Black-backed |

| Ground foraging | Northern Flicker |

| Sap well drilling | Red-breasted Sapsucker |

| Bark gleaning | White-headed Woodpecker |

Drumming and Communication

Ever wonder how woodpeckers announce their presence without singing? Through drumming patterns, these birds create acoustic signatures for mate attraction and territorial defense. You’ll hear distinct communication styles—Downy Woodpeckers drum 16-18 beats per second, while Hairy Woodpeckers reach 20. Identifying woodpeckers by sound becomes easier when you recognize:

- Downy Woodpecker: Short bursts under 1 second

- Hairy Woodpecker: 1.5-second drums

- Pileated Woodpecker: Intense 3-second blasts

- Red-breasted Sapsucker: Slow, uneven rhythms

- American Three-toed: Long drums with fade-out effect

Peak woodpecker calls and drumming occur during the spring breeding season, serving key roles in bird behavior and nesting communication.

Nesting and Breeding Habits

Woodpeckers are meticulous architects when raising their young, with nest site selection heavily dependent on dead or dying trees. White-headed Woodpeckers favor ponderosa pine snags averaging 41 feet tall, while Northern Flickers opt for cavities located 6.5–10 feet above the ground. Across Washington, breeding seasons peak from April through June, with males taking on the task of excavating tree cavities. Both parents share incubation duties during this critical period.

| Species | Clutch Size | Incubation Period |

|---|---|---|

| Downy Woodpecker | 3-8 eggs | 12 days |

| Hairy Woodpecker | 2-9 eggs | 14 days |

| Pileated Woodpecker | 3-7 eggs | 8-12 days |

Fledging success varies among species, with White-headed Woodpeckers averaging 2.54 young per nest. This demonstrates how nesting behaviors adapt to habitat quality. The timing of the mating season also plays a crucial role in productivity. Lewis’s Woodpeckers, for instance, exhibit higher productivity with earlier clutches, while later nests face increased predation around mid-June.

Seasonal Movements and Migration

Unlike many bird families, most woodpeckers in Washington don’t follow traditional migration patterns. Instead, you’ll observe subtle seasonal shifts shaped by elevation and food supply. Here’s what drives their movements:

- Partial Migration: Northern Flickers peak southward from mid-September through late October

- Altitudinal Shifts: Williamson’s Sapsuckers descend from 1,200 to 700 meters between October and December

- Nomadic Movements: Lewis’s Woodpeckers wander hundreds of kilometers tracking food availability

- Climate Impact: Warmer winters trigger earlier arrivals and departures

- Habitat Influence: Forest fires and logging alter traditional movement routes

What Woodpeckers Eat in Washington

Washington’s woodpeckers aren’t picky eaters, but they’ve each carved out their own niche in terms of finding food. Some species are laser-focused on insects hiding under bark, while others have developed a taste for sap or even aerial acrobatics to catch flying bugs.

Let’s break down what’s on the menu for these birds and how their diets shape where you’ll find them.

Insect-based Diets

If you’ve ever wondered what fuels those relentless pecking sessions, here’s the answer: insects make up 75–85% of most woodpecker diets in Washington. You’ll find them targeting beetle larvae, ants, and caterpillars with surgical precision. Their digestive adaptations—including barbed tongues and strong gizzards—let them process hard exoskeletons efficiently, while seasonal variation means they’ll shift to more plant matter when bugs become scarce.

| Species | Primary Insect Prey |

|---|---|

| Downy Woodpecker | Beetles, ants, caterpillars |

| Hairy Woodpecker | Wood-boring beetle larvae |

| Northern Flicker | Ants (45% of diet), termites |

| Pileated Woodpecker | Carpenter ants (up to 85%) |

| Red-breasted Sapsucker | Wasps, beetles at sap wells |

This insect foraging delivers serious ecological impact—woodpecker predation can slash tree pest populations by up to 98%, keeping Washington’s forests healthier and more resilient.

Woodpecker predation can slash tree pest populations by up to 98%, keeping Washington’s forests healthier and more resilient

Sap Feeding Species

While most woodpeckers hunt insects, three specialists—Red-breasted Sapsucker, Williamson’s Sapsucker, and the rare Red-naped Sapsucker—drill sap wells in tree bark. You’ll spot these shallow rows of holes feeding not just the woodpeckers but entire communities of insects and birds, establishing them as keystone resource providers.

Sap-feeding migration patterns shift with freezing temperatures, pushing Red-breasted Sapsuckers to lower elevations where sap wells remain productive through winter.

Fruit, Nut, and Seed Consumption

Beyond insects and sap, you’ll find Washington woodpeckers surprisingly fond of plant-based foods—especially when seasons shift. Fruit, nuts, and seeds can make up over 50% of their diet in late summer and fall, providing essential fats for winter survival.

Key seasonal preferences include:

- White-headed Woodpeckers specialize on Ponderosa Pine seeds east of the Cascades during fall and winter

- Northern Flickers consume wild and cultivated fruits like apples and berries, with nuts and seeds reaching 30% of annual intake

- Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers cache acorns and berries in bark crevices for leaner months

This dietary flexibility explains why sunflower seeds, peanuts, and suet feeders work so well for attracting woodpeckers to backyards—you’re matching their natural foraging techniques and energy balance needs.

Attracting Woodpeckers to Your Backyard

Want to turn your backyard into a woodpecker hotspot? It’s easier than you might think—you just need to offer the right combination of food, habitat features, and shelter.

Let’s look at three practical ways you can make your property irresistible to these fascinating birds.

Best Foods and Feeders

If you want to master attracting woodpeckers to backyards, start with suet feeders—they’re your best bet for drawing in Downy, Hairy, and Pileated species year-round. Peanuts and black oil sunflower seeds offer excellent peanut attraction and seed choices, especially in winter. Fruit offerings like apples or grape jelly appeal to Red-breasted Sapsuckers and Northern Flickers.

Smart feeder placement near tree trunks boosts visits considerably, tapping into natural woodpecker feeding habits.

Creating Woodpecker-friendly Habitats

Your yard can become a woodpecker haven with a few strategic changes. Keep standing dead trees—snags—whenever safe, since Washington’s cavity-nesting species depend on them for foraging and nesting. Aim for at least 20% forest cover in suburban areas to support Pileated Woodpeckers.

Skip pesticides to protect the insects woodpeckers eat, and let some logs decay naturally to boost habitat quality for attracting woodpeckers to yards.

Native Plants and Nest Boxes

To support Washington’s woodpeckers through native plant selection and nest box design, you’ll need thoughtful planning. A University of Delaware study found yards need 70% native coverage for successful fledging—here’s how to start:

- Plant red-flowering currant and oceanspray for early-season insects

- Install nest boxes with six inches of wood shavings

- Retain snags as natural tree cavities

- Monitor nest boxes annually for occupancy

These conservation linkages strengthen bird habitat and wildlife conservation across Washington State, especially when paired with habitat restoration burns.

Conservation Status of Washington Woodpeckers

Not all of Washington’s woodpeckers are thriving—some face serious threats that put their future at risk. Habitat loss, logging, and changing landscapes have hit certain species harder than others, while federal protections work to keep populations stable.

Here’s what you need to know about which woodpeckers are struggling and what’s being done to help them.

Threatened and Endangered Species

You’ll find that Washington’s woodpecker populations face varying levels of risk. The White-headed Woodpecker holds sensitive status in parts of its range, while the Black-backed Woodpecker remains a candidate species statewide. Though no Washington woodpeckers currently carry federal endangered status, legal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act safeguard all species from disturbance.

| Species | Conservation Status |

|---|---|

| White-headed Woodpecker | Sensitive in Washington |

| Black-backed Woodpecker | State Candidate Species |

| Lewis’s Woodpecker | Forest Service Sensitive |

| Most Other Species | Federally Protected |

Climate impacts and habitat alteration continue threatening these birds. Population trends show Lewis’s Woodpecker declining 48% over fifty years, while White-headed populations grow slowly at 1.1% annually.

Collaborative efforts between agencies, tribes, and landowners drive wildlife conservation forward through monitoring programs and habitat management across Washington State wildlife areas.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Across Washington’s forests, habitat loss strikes hardest at specialist species like the White-headed Woodpecker, where old-growth decline and fragmentation effects force birds into home ranges three times larger than normal. Urbanization impacts compound these pressures through measurable changes in woodland habitats:

- Ponderosa pine forests have lost 92–98% of old-growth stands to logging

- White-headed Woodpeckers need landscapes with 26% old-growth minimum

- Fragmented areas increase territory sizes from 104 to 342 hectares

- Fire suppression alters forest structure essential for Lewis’s Woodpeckers

- Reduced patch sizes in urban areas decrease woodpecker diversity

Habitat restoration efforts now target these critical wildlife conservation needs through improved forest ecology management.

Conservation Efforts and Protections

Washington’s woodpecker conservation status benefits from multi-layered legal protections, including federal migratory bird treaty act coverage and the pileated woodpecker’s State Candidate designation.

Collaborative efforts unite agencies, tribes, and landowners in habitat restoration—restoring ponderosa forests, creating snags, and maintaining nest boxes.

Wildlife management and protection strategies integrate nesting support programs with public engagement campaigns, making woodland bird conservation a shared responsibility across environmental conservation efforts statewide.

Woodpeckers’ Role in Forest Ecosystems

Woodpeckers aren’t just noisy neighbors—they’re ecosystem engineers that keep Washington’s forests healthy and thriving. From controlling destructive insect populations to creating homes for dozens of other species, these birds punch way above their weight class in ecological importance.

Let’s look at three key ways woodpeckers shape the forests around them.

Insect Control and Tree Health

Woodpeckers deliver natural pest population control that directly impacts tree mortality rates in Washington’s forests. By focusing their foraging tree selection on infested trees, these insectivorous birds reduce woodboring insects like bark beetles, protecting overall forest ecology and wildlife health.

Their ecological role includes:

- Targeting carpenter ants and beetle larvae that would otherwise kill healthy trees

- Preferring burned forest effects areas where pest insects thrive

- Providing measurable ecological health contributions through their insect diet

Creating Nest Cavities for Other Wildlife

Think of woodpeckers as nature’s landlords—they excavate tree cavities that over 40 species depend on for nesting sites. Cavity insulation benefits are real: they stay 18°F warmer than outside air. Different cavity size preferences matter for forest wildlife and conservation.

You’ll find bluebirds, chickadees, and flying squirrels moving into these wildlife habitats within a year. This ecological role drives secondary nester competition and shapes forest management implications. Mammal cavity users like raccoons and bats also benefit from these essential tree cavities.

| Woodpecker Species | Typical Secondary Nesters |

|---|---|

| Pileated Woodpecker | Wood ducks, barred owls |

| Northern Flicker | American kestrels, saw-whet owls |

| Hairy Woodpecker | White-breasted nuthatches, smaller owls |

| Downy Woodpecker | Chickadees, wrens |

| Red-breasted Sapsucker | Swallows, titmice |

Indicator Species for Forest Health

Beyond creating homes for other species, you’ll find these birds reveal what’s really happening in woodland ecosystems. Woodpeckers in Washington serve as forest health indicators—their presence tells you about biodiversity correlation, pest control effectiveness, and disturbance response patterns.

Here’s what monitoring trends show:

- Sites with 5+ woodpecker species have 32% higher avian richness

- Black-backed populations surge 11x after high-severity fires

- Hairy Woodpeckers target bark beetle infestations in 70% of feeding events

- Coniferous forests and woodpeckers together signal ecosystem function scores

- Woodpecker habitats and ranges predict vertebrate diversity across 22 million surveyed acres

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many types of Woodpeckers are there in Washington State?

You’ll find 11 confirmed woodpecker species regularly pecking around the state, plus two accidental visitors—talk about a full house! This diversity reflects varied forest ecosystems statewide.

Where do woodpeckers live in Washington?

In Washington State, you’ll find woodpecker habitats ranging from riparian forests and burned woodlands to suburban backyards.

Elevation gradients and forest fragmentation shape woodpecker range, with species showing striking suburban adaptability across diverse landscapes.

Are woodpeckers legal in Washington State?

You can’t hunt or harm woodpeckers in Washington. Federal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and state regulations make it illegal without permits, reinforcing wildlife conservation and bird conservation enforcement measures.

Are pileated woodpeckers common in Washington State?

Pileated woodpeckers are uncommon residents across Washington’s forested regions, not rare but less abundant than downy or hairy woodpeckers.

You’ll spot them more often in western Washington’s mature forests than eastern areas.

What do woodpeckers eat in Washington State?

Picture a Downy Woodpecker clinging to your backyard suet feeder—that’s just a snack. Insectivorous birds like woodpeckers and tree sap lovers feast primarily on beetle larvae, carpenter ants, and other grubs hidden beneath bark, supplementing with seasonal diets.

Are black backed woodpeckers common in Washington State?

No, Black-backed Woodpeckers aren’t common in Washington. They’re uncommon permanent residents in eastern mountain conifer forests, with populations below the 2,000-pair viability threshold.

Post-fire abundance increases temporarily when woodpeckers colonize burned forests.

Are there woodpeckers in Washington State?

Yes, Washington State hosts thirteen confirmed woodpecker species, including eleven regular residents and two accidental visitors. You’ll find everything from common Northern Flickers to rare White-headed Woodpeckers across diverse habitats statewide.

What does a woodpecker look like in Washington State?

Washington woodpeckers show distinctive size differences and identifying characteristics—from tiny 6-inch Downies to massive 19-inch Pileateds.

Look for black-and-white plumage variations, red crests, and specialized bill shapes that help distinguish each species across regional differences.

Are white-headed woodpeckers common in Washington State?

If you’re scanning the ponderosa pines near Wenas Campground, you won’t see this woodpecker species on every hike. White-headed woodpeckers are uncommon to rare in Washington State, facing population decline from habitat loss and fire suppression throughout their limited geographic hotspots in eastern counties.

Are Lewis’s woodpeckers common in Washington State?

Unfortunately, Lewis’s Woodpecker is uncommon to rare across Washington State, with populations declining sharply due to habitat loss.

You’ll have the best chance spotting them in eastern Washington’s open ponderosa pine forests.

Conclusion

Every drumbeat you hear now carries a story—once you’ve learned to listen, you’ll never walk through a Washington forest the same way again. These eight woodpeckers of Washington don’t just inhabit the landscape; they sculpt it, one excavation at a time.

Whether you’re tracking a Pileated’s booming call through old-growth or watching a Downy work your backyard snag, you’re witnessing forest architects at work. The conversation’s been happening all along. You’re just finally fluent.

- https://avibirds.com/woodpeckers-in-washington/

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5434074.pdf

- https://www.eopugetsound.org/articles/white-headed-woodpecker-picoides-albolarvatus

- https://www.simplybirding.com/birds/white-headed-woodpecker-dryobates-albolarvatus/

- https://birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/white-headed_woodpecker