This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

Understanding what different birds eat reveals not just dietary preferences, but the striking anatomical adaptations that define each species’ ecological role. From the curved beaks of nectar-feeders to the razor-sharp talons of raptors, feeding strategies determine which birds visit your backyard and what foods will bring them back.

Whether you’re stocking feeders or simply observing wild populations, recognizing these dietary patterns transforms casual birdwatching into informed wildlife stewardship.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Birds Eating Habits

- What Do Birds Eat

- Bird Diet Categories

- Safe Bird Feeder Foods

- Birds Hunting Techniques

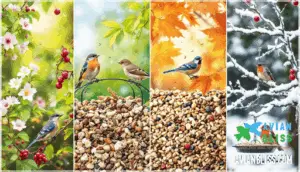

- Seasonal Bird Feeder Foods

- Bird Feeding Habits

- Bird Species Diets

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Do birds remember you if you feed them?

- Will all birds eat meat?

- What food can I give wild birds?

- Can birds eat rice or pasta safely?

- Do birds eat nuts like almonds or walnuts?

- How does diet affect bird plumage color?

- Can birds eat spicy peppers like chili?

- What foods help improve birds’ immune systems?

- Do birds need different foods when molting?

- How often should I clean bird feeders?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Birds have evolved into four primary feeding guilds—seed-eaters, frugivores, nectar-feeders, and insectivores—each with specialized anatomical adaptations like beak shape, tongue structure, and digestive efficiency that determine which foods they can process and which habitats they occupy.

- Seasonal dietary shifts are dramatic and driven by physiological demands: breeding birds require up to 70% insect protein for egg production and chick development, migratory species increase fat reserves by 40% through fall hyperphagia, and winter survivors depend on calorie-dense foods like suet and black-oil sunflower seeds to offset extended fasting periods.

- Effective backyard feeding requires matching food types to species-specific preferences and nutritional profiles—nyjer seed attracts finches with its 35% fat content, safflower’s bitter flavor deters bully birds while drawing cardinals, and mealworms provide the 53% protein insectivores need during nesting season.

- Hunting techniques reveal striking ecological specialization: raptors adjust feeding rates inversely to body size (small species consume 20-25% of body weight daily versus 3.5% for large raptors), shorebirds probe sediments at species-specific depths based on bill morphology, and specialized feeders like sapsuckers maintain tree sap wells that support over 35 additional bird species.

Birds Eating Habits

Birds have developed remarkably specialized eating habits that reflect their unique anatomical adaptations and ecological niches. Understanding these feeding strategies helps you identify which species might visit your backyard and what foods will attract them.

Let’s explore the four primary feeding guilds that define how birds obtain their nutrition.

Seed-eating Birds

Seed-eating birds, or granivores, have evolved specialized beaks perfectly adapted for cracking open seeds with striking efficiency. You’ll notice these birds demonstrate clear seed preferences based on nutritional value and handling ease. Research shows that birds favor high-energy options like nyjer seed, which contains 18% protein and 35% fat, making it ideal during energy-intensive periods.

Different species display distinct foraging behaviors:

- Finches crack sunflower seeds, nyjer, and millet with their cone-shaped beaks

- Cardinals prefer sunflower hearts and safflower seeds for easy access

- Goldfinches specialize in thistle and composite seeds

- Sparrows consume grass seeds and millet efficiently

- Doves handle larger seeds like canary seed and rapeseed

Studies indicate that dietary adaptation varies seasonally, with seed intake increasing during migration when energy demands double. This relationship highlights the importance of seed dispersal for both birds and plants.

Frugivores

Frugivorous birds—the fruit eaters of the avian world—have mastered the art of extracting nutrition from nature’s sweetest packages. You’ll find over 1,700 species worldwide classified as frugivores, with tropical forests hosting the highest diversity, where they can make up nearly half the bird community.

These fruit-loving birds don’t just grab any berry they spot; they carefully regulate their intake to balance macronutrients, favoring carbohydrate-rich fruits while fine-tuning their diet across multiple species. Their feeding efficiency is striking—some process over 100 fruits per hour with handling times under two seconds.

By dispersing seeds from more than 50% of tropical forest trees, frugivores link fruit availability directly to forest regeneration, moving up to 2,000 seeds daily during peak periods. Studies show they often prioritize nutrient intake regulation over maximizing energy gain.

Nectar-eating Birds

Nectar-feeding birds have developed remarkable adaptations through Coevolution Dynamics with flowering plants, creating one of nature’s most elegant partnerships. You’ll encounter three major groups—hummingbirds, honeyeaters, and sunbirds—each displaying specialized intestinal sucrase that permits rapid Sucrose Digestion at near-perfect efficiency. Their Metabolic Demand ranks among the highest in the avian world, with field metabolic rates exceeding five times basal levels during active feeding periods. These nectarivorous species consume nectar at concentrations averaging 20–25% sugar by weight, balancing energy payoff against viscosity that would slow drinking rates. Water Balance becomes critical as they process volumes approaching their body weight daily, managing excess fluid through efficient renal output while maintaining ionic stability.

- Hummingbirds achieve nearly 100% digestive efficiency for sugar-rich nectar through specialized paracellular transport pathways

- Choice Nectar Concentration of 20–25% matches bird tongue mechanics, though viscous-feeding insects prefer stronger solutions around 35%

- Their Pollination Role extends to thousands of angiosperm species across tropical and temperate biomes

- Nectar Composition drives floral evolution toward specific colors, morphologies, and sugar profiles optimized for avian visitors

- Most nectarfeeding birds supplement with insects or fruit when blooms decline, sustaining energy through seasonal gaps

Insectivores

While nectar-feeders focus on flowers, insectivorous birds tackle a different menu entirely—one that crawls, flies, and buzzes. These avian pest control experts consume roughly 400–500 million metric tons of insects annually worldwide, with beetles, flies, and moths topping their grocery list. You’ll notice their hunting methods vary dramatically based on prey selection and habitat.

Adaptations for insect foraging include:

- Nighthawks sweeping through dusk skies with mouths agape, netting airborne bugs

- Bluebirds perching motionlessly before swift ground strikes

- Woodpeckers wielding specialized tongues that probe bark crevices for hidden larvae

- Swallows executing mid-air acrobatics to snatch mosquitoes during flight

- Flycatchers using ambush tactics from strategic perches

Their foraging behavior directly shapes agricultural health and forest stability, yet insectivorous birds face troubling population declines—over 2.9 billion individuals lost in North America alone during recent decades. The nutritional value and impact of insects on avian diets can’t be overstated for these irreplaceable insect regulators.

What Do Birds Eat

Birds don’t just eat seeds—their dietary diversity spans over 11,000 species consuming everything from nectar to vertebrates. You’ll observe striking feeding adaptations shaped by habitat influence and food availability.

Roughly 75% of bird species consume insects during some life stage, while granivorous species like finches specialize in seeds, and hummingbirds require high-energy nectar. These avian diets reflect nutritional needs that shift with seasons and ecosystems.

Understanding bird eating habits reveals how each species has evolved specialized feeding strategies—from raptors consuming 10-15% of their body weight daily in prey to frugivorous toucans dispersing forest seeds through their selective consumption patterns.

Bird Diet Categories

Birds don’t all eat the same way—some stick to plants, others hunt for meat, and many mix it up depending on what’s around. Understanding these basic diet categories helps you see why different species show up at your feeder or backyard at different times.

Let’s break down the main groups and how their feeding habits shift with the seasons.

Herbivores

When you’re watching plant-eating birds in action, you’re witnessing evolutionary adaptations that span millions of years across at least 13 independent lineages. Herbivorous birds rely exclusively on plants, seeds, and fruits, with their longer intestines—up to 40% more than carnivores—helping break down tough plant material. Their specialized digestive systems turn vegetation into usable energy, though they extract about one-third less energy than insect-eaters do from their meals.

Herbivore adaptations include powerful gizzards generating forces over 270 N/cm².

- Granivorous species like finches get 80–95% of their energy from seeds

- Frugivorous birds consume fruits with pulp-to-seed ratios exceeding 3:1

- Nectar foraging birds obtain up to 90% of calories from floral sources

- Herbivore adaptations include powerful gizzards generating forces over 270 N/cm²

Your backyard seed dispersal helpers have evolved striking fruit preferences and plant digestion strategies.

Omnivores

When you’re observing omnivorous birds, you’re watching nature’s dietary jack-of-all-trades—species that split their menu nearly evenly between plants and animals. Across global avian studies, about 12% of birds fit this category, consuming no single food type for more than half their diet.

Their feeding strategies showcase striking seasonal plasticity, with temperate species loading up on insects during spring breeding and pivoting to seeds and fruits when winter arrives. This dietary adaptability creates essential trophic linkages in ecosystems, connecting plant and animal food webs. Yet omnivory functions as an evolutionary sink, showing higher extinction rates than specialized feeding habits.

| Species Group | Primary Foods |

|---|---|

| Crows & Ravens | Insects, seeds, carrion, small vertebrates |

| Woodpeckers | Larvae, sap, seeds, nuts |

| Thrushes | Fruits, beetles, earthworms |

| Ducks | Aquatic plants, invertebrates, fish eggs |

| Gulls | Fish, invertebrates, human food waste |

Your backyard omnivores balance protein from insects with carbohydrates from seeds, requiring specific amino acid ratios—about 20 mg/day of lysine and 12 mg/day of methionine—to maintain body mass and metabolic function.

Carnivores

When raptors lock onto their targets, you’re witnessing predatory precision honed over millions of years. Carnivorous birds of prey—representing roughly 18% of all avian species—have evolved specialized hunting techniques that make them nature’s most effective aerial hunters. These meat-eating raptors consume diets dominated by mammals, reptiles, fish, and other birds, with intake rates scaling inversely to body size.

Predation impact varies dramatically by hunting method:

- Spanish imperial eagles achieve 100% success hunting reptiles versus lower rates for mammalian prey

- Female raptors outperform males in flight hunting, with success rates reaching 58.9% compared to 41.06%

- Cooper’s Hawks specialize in medium-sized birds like starlings, while Sharp-shinned Hawks target smaller species like juncos

- Ferruginous hawks show highest hunting efficiency from high flight at 20.8% success

- Small raptors consume 20-25% of their body weight daily, while larger species need only 3.5%

Prey specialization allows multiple raptor species to coexist without direct competition, each filling distinct ecological niches.

Seasonal Variations

Throughout the year, your backyard feeders witness a striking transformation in avian appetites—a demonstration of birds’ adaptive resilience. Dietary shifts align precisely with physiological demands: breeding season (spring) triggers heightened protein intake, with songbirds deriving up to 70% of their diet from insects to fuel egg production and chick development. Migration patterns drive fall hyperphagia, where species like yellow-rumped warblers increase fat reserves by 1.4-fold compared to winter levels. Winter survival depends on calorie-dense foods—suet, black-oil sunflower seeds, and nuts—that compensate for extended nocturnal fasting and thermoregulatory costs.

Food availability fluctuates with precipitation cycles—Central Himalayan insectivores show peak species richness post-monsoon when insect populations surge. Seasonal bird feeder foods should mirror these natural patterns, supporting resident and migratory species through critical bottleneck periods.

| Season | Primary Food Sources | Nutritional Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Spring/Summer | Insects, mealworms, nectar | Protein for breeding, growth |

| Fall | Seeds, nuts, berries | Fat accumulation for migration |

| Winter | Suet, sunflower seeds, high-fat blends | Energy for survival, insulation |

Safe Bird Feeder Foods

If you’re ready to set up a bird feeder, choosing the right foods makes all the difference in attracting a diverse array of species to your yard. Not all birdseed is created equal, and understanding which options provide the best nutrition helps you support your feathered visitors year-round.

Here are five safe, high-quality foods that’ll keep your backyard birds healthy and coming back for more.

Nyjer Seed

Nyjer seed delivers powerhouse nutrition to your backyard finches, containing approximately 35% fat and 20% protein—precisely the high-energy fuel these small birds need. Originating from the African Daisy (Guizotia abyssinica) and cultivated primarily in Ethiopia, India, and Myanmar, this sterilized seed won’t sprout unwanted plants in your garden while attracting American Goldfinches, House Finches, Purple Finches, and Pine Siskins.

When offering Nyjer seed, you’ll need specialized feeder designs:

- Use tube feeders with tiny ports sized for small finch bills

- Store seed in cool, dry locations to preserve its 25% oil content

- Replace every 3-4 months to maintain nutritional value and freshness

- Consider mesh "thistle socks" for clinging species like siskins

Market trends show Nyjer’s popularity peaks during winter months when caloric demands increase, making it essential among bird food types for attracting wild birds year-round.

Suet

Suet, composed of rendered beef fat from cattle kidneys and loins, delivers over 800 kilocalories per 100 grams, making it one of the most concentrated safe bird feeder foods available. More than 20 backyard bird species consume this high-energy resource, including woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches, wrens, and bluebirds that might otherwise skip seed-based offerings.

You’ll find seasonal suet formulations designed for year-round feeding of wild birds:

| Season | Suet Type |

|---|---|

| Winter | Pure rendered fat for maximum calories |

| Summer | Melt-resistant blends with reduced dripping |

| Year-round | Mixed formulations with insect protein |

Suet ingredients vary widely—commercial suet cake products incorporate sunflower seeds, peanuts, dried fruits, and freeze-dried mealworms to attract diverse species. Home recipes allow customization of bird food blends, though store-bought options guarantee proper fat rendering.

The benefits of suet extend beyond nutrition: feeders create minimal waste since no hulls accumulate, and approximately 54% of North American feeding stations now include suet in their backyard bird feeding programs.

Safflower Seed

Safflower seed’s distinctive bitter flavor creates a natural pest deterrent, driving away grackles, starlings, and squirrels while attracting cardinals, chickadees, and nuthatches to your feeding station. You’ll appreciate that this seed type’s strategy reduces bully bird competition by over 60%, a pattern documented in multiple backyard surveys of seed-eating birds. Northern Cardinals consistently favor safflower alongside sunflower offerings, making it essential for attracting cardinals year-round.

Nutritional value stands out: safflower seed contains 38% fat and 16% protein, exceeding most bird food options in energy density. Consider these benefits:

- Golden safflower provides 30% more fat than white varieties, supporting high-metabolism species during winter

- Feeder types like hopper and tube designs accommodate diverse bill strengths, from finches to grosbeaks

- Market trends show premium safflower blends command prices 20–40% higher, reflecting increased demand for quality bird diets

White-breasted Nuthatches and Mourning Doves demonstrate repeated daily visitation at safflower-stocked feeders, confirming species-specific preferences.

Black-oil Sunflower Seed

Black-oil sunflower seeds dominate bird feeders across North America, attracting over 70% of feeder-visiting species with their thin shells and high oil content. You’ll find cardinals, chickadees, titmice, woodpeckers, and finches eagerly consuming these nutritional powerhouses, which contain 27–29% fat, 24–26% fiber, and 14% protein.

Project WildBird documented preferences among 98 species, with Mourning Doves (89%), Blue Jays (85%), and American Goldfinches (82%) showing strong selection for black oil seeds over alternative offerings.

Their year-round appeal bolsters energy demands during migration, breeding seasons, and winter survival, making them the cornerstone of backyard bird food strategies.

Mealworms

While sunflower seeds attract seed-eaters, mealworms draw insectivores like Eastern Bluebirds, American Robins, and Downy Woodpeckers to your feeding station. These insect-hunting birds benefit from mealworms’ outstanding nutritional value, with dried forms containing 53% protein and 28% fat—perfect for supporting breeding adults and nestlings during nesting periods from March through August. You’ll find these feeding habits mirror natural foraging behaviors, triggering ecological impact that strengthens local bird populations.

- Offer live mealworms for moisture content (62%) that aids hydration in dry climates

- Store dried mealworms year-round in airtight containers, mixing with seeds for dietary balance

- Increase feeding practices during spring when protein demands peak for egg production

Birds Hunting Techniques

Birds have evolved impressive hunting strategies that reflect their dietary needs and environmental niches. From the lightning-fast strikes of raptors to the patient probing of shorebirds, each species has developed specialized techniques for capturing prey.

Let’s examine how different bird groups locate, pursue, and secure their meals.

Raptors

Raptors rely on hunting strategies refined over millennia, with prey selection varying dramatically by species and size. Spanish imperial eagles engage in flight hunting 42% of the time, scavenging 30%, perch hunting 16%, and kleptoparasitism 12%. Small raptors weighing 100–200 grams consume 20–25% of their body weight daily, while those over 7,000 grams eat just 3.5%. Climate impact has shifted feeding rates, with early-season migrants showing increased feeding activity, while late-migrating raptors face reduced prey availability.

| Raptor Type | Primary Prey & Hunting Strategy |

|---|---|

| Kestrels | Insects; hovering and pouncing |

| Red-tailed Hawks | Small mammals; perch hunting |

| Ospreys | Fish (75% menhaden); aerial diving |

| Spanish Imperial Eagles | Mixed vertebrates; flight hunting and scavenging |

| Crested Caracaras | Mammals (31.4%), reptiles (24.1%); opportunistic feeding |

Captive diets require whole vertebrate prey with vitamin supplementation to compensate for nutrient loss in frozen-thawed food.

Shorebirds

Shorebird diets reveal striking prey specialization, with smaller species like Curlew Sandpipers deriving 83% of their intake from polychaetes, while Red Knots focus on bivalves (78% of diet). Foraging adaptations are closely tied to bill morphology: curlews probe deep sediments with their elongated bills, whereas plovers visually hunt on exposed surfaces. Seasonal diets shift during pre-migratory fuelling periods, when energy-dense crustaceans and polychaetes become critical. Geographic variation further shapes waterfowl and shorebird feeding techniques—gastropods dominate in Hangzhou Bay (32.7% dietary contribution), reflecting habitat-specific prey availability. These nutritional implications demonstrate how shorebird feeding techniques maintain coastal food web dynamics through resource partitioning.

Key Shorebird Feeding Characteristics:

- Bill specialization determines prey access depth and capture method

- Tidal cycles dictate foraging windows and substrate exposure

- Species-specific prey preferences reduce interspecific competition

- Pre-migration energy demands drive seasonal diet composition changes

- Morphological constraints limit profitable prey size ranges for each species

Nocturnal Birds

When the sun sets, nocturnal birds like owls and nightjars rely on specialized adaptations that transform darkness into opportunity. Their hunting strategies differ dramatically from diurnal species, employing silent flight enabled by fringed feather edges that eliminate aerodynamic noise during prey approach.

Tawny Owls target small mammals—voles, mice, shrews, and rats—while Brown Fish-Owls demonstrate considerable prey specialization, with crabs comprising over 75% of their diet composition in certain habitats. Night herons hunt aquatically, remaining motionless near water before striking swiftly at frogs, fish, and insects. Nocturnal prey selection shifts based on local abundance, reflecting adaptive influences that allow opportunistic feeding.

Pellet analysis reveals outstanding dietary breadth; barn owl pellets contain 17–18 taxa—three times more species than live-trapping captures—demonstrating how predatory birds’ foraging strategies provide valuable ecological data about small mammal populations across extensive temporal and spatial scales.

Aerial Dives

Falcon stooping represents the pinnacle of aerial predation, with peregrine falcons achieving dive angles optimized between 100–1000 meters, hitting speeds of up to 320 km/h through wing compression that minimizes drag. These raptors demonstrate hunting strategies where diving energetics translate directly into prey capture success—Lesser Kestrels achieve a 32.8% dive success rate, while hovering yields 31.5% capture rates. Aerial dives require split-second adjustments for trajectory control, enabling prey interception mid-flight with striking precision.

Key factors influencing hunting success include:

- Dive angle optimization: Steeper stoops (>30°) generate audible wing sounds, maximizing acceleration toward prey

- Flight mode transitions: Preceding behaviors greatly affect strike outcomes (χ² = 8.75, p = 0.033)

- Proportional navigation: Raptors employ fixed-point targeting mechanisms during terminal attacks

- Environmental timing: Breeding stage, wind speed, and time of day shape aerial hunting patterns

- Prey size trade-offs: Little Blue Herons’ 25% aerial success rate yields larger, higher-calorie prey than wading methods

Your understanding of bird diets deepens when you recognize how diving energetics separate specialized hunters from opportunistic feeders.

Seasonal Bird Feeder Foods

Birds’ nutritional needs shift with the seasons, and understanding these changes helps you provide the right foods year-round. What you offer in your feeder during spring breeding season differs greatly from what sustains them through harsh winter months.

Here’s how to match your feeder offerings to each season’s specific demands.

Spring Diet

When spring arrives, birds ramp up their energy intake by up to 40% to fuel migration and breeding diets. You’ll notice they’re constantly foraging because their protein requirements jump 20–30% as they prepare for nesting. This shift in spring nutrition means birds move away from winter’s fat-heavy food sources toward insects and calcium sources that support strong eggshell formation.

Your feeder should focus on these high-protein options:

- Mealworms (live or dried) for robins and blackbirds raising chicks

- Suet pellets providing essential fats during cold snaps

- Sunflower hearts and peanut granules for calorie-dense feeding habits

- Fresh fruit slices offering hydration and vitamins

- Clean water for drinking and feather maintenance

Insect abundance remains limited early on, so your supplemental seeds and insects bridge the gap until natural food sources emerge.

Summer Diet

When summer arrives, you’ll see your backyard transform into an all-you-can-eat buffet for birds. Insect abundance doubles compared to spring, with warblers and flycatchers consuming over 70% of flying insects during the breeding season. Meanwhile, orioles and tanagers feast on ripening berries—blackberries, serviceberries, and mulberries—that fuel their sky-high metabolic rates. Cardinals and finches reduce seed consumption by 30–50% when these summer insects and fruits become available, showing clear foraging changes as natural foods overtake feeder offerings.

Breeding nutrients matter more than ever now. Nestlings require diets composed of up to 90% insects and larvae, while parent birds increase their energy expenditure by 60% during chick-feeding. You’ll notice females seeking calcium-rich sources like crushed shells for stronger eggshells, and molting adults need 20–30% more protein for feather regeneration.

| Food Source | Primary Summer Consumers |

|---|---|

| Flying insects (flies, moths, beetles) | Warblers, flycatchers, swallows |

| Soft fruits (cherries, mulberries) | Orioles, tanagers, robins |

| Nectar from salvia and honeysuckle | Hummingbirds (consuming 2× body weight daily) |

| Ground invertebrates (worms, grubs) | Thrushes, robins in irrigated lawns |

Urban diets shift dramatically—25–35% now comes from feeders in cities. If you’re feeding in summer, keep hummingbird feeders stocked (they’ll drain 100–150 ml daily) and offer no-melt suet for chickadees. Clean feeders every 2–3 days since warm weather breeds bacteria fast. Remember, supplemental feeding won’t disrupt migration; daylight and hormones control that instinct, not your generosity.

Fall Diet

Fall brings dramatic shifts in your birds’ nutritional needs. As insect populations crash, you’ll witness fall hyperphagia—an instinct-driven feeding frenzy where warblers pack on 40% of their body weight as fat. Native berries like dogwood and serviceberry supply lipid-rich fuel, composing over 60% of migratory robins’ diets, while invasive fruits get ignored for their poor nutrition. Meanwhile, chickadees and jays begin autumn caching, hoarding hundreds of sunflower seeds and peanuts for winter survival.

- Black-oil sunflower seeds meet seed preferences for quick energy and minimal waste

- Suet benefits woodpeckers and titmice with concentrated fat reserves

- Dried fruit and mealworms help frugivores adjust to seasonal dietary shifts

Winter Diet

When temperatures plummet, your winter birds shift into survival mode, relying on high-fat foods to offset metabolic demands during long, freezing nights. Over 50 million Americans support winter foraging by providing suet benefits and black-oil sunflower seeds—favorites that deliver concentrated energy when natural food disappears. Seed caching species like chickadees tap into fall reserves, while consistent bird feeding increases local survival rates by 25–30%.

The habitat role of native plants matters too: winterberry and dogwood sustain frugivores, and evergreens shelter cached stores. Pair feeding habits with unfrozen water, and you’ll boost breeding success come spring.

Bird Feeding Habits

Birds don’t just eat differently—they feed differently, shaped by unique metabolic demands and sensory adaptations you mightn’t expect. Understanding these feeding habits helps explain why certain species visit your feeder at specific times or seem to favor particular setups.

Here’s what drives their daily feeding behaviors.

High Metabolism

Avian physiology is a marvel of biological efficiency. Birds maintain basal metabolic rates 50–70% higher than mammals of equivalent mass, requiring small passerines to consume food equivalent to 25–30% of their body weight daily. This remarkable energy expenditure drives constant foraging behavior across species.

Different dietary strategies reflect these metabolic demands:

- Insectivores hunt protein-rich invertebrates throughout daylight hours to fuel their rapid oxygen consumption

- Nectar-feeding hummingbirds achieve daily energy turnovers exceeding ten times their basal rate, compensating for sugar-rich but nutrient-poor diets

- Seed-eating finches maintain elevated resting metabolism through continuous muscle activity during foraging

Your backyard visitors aren’t just eating—they’re managing intricate thermoregulation systems that demand precise nutritional balance to survive.

Vision and Smell

Your understanding of bird metabolism sets the stage for appreciating how birds actually locate their meals. Vision dominates avian foraging, with raptors achieving exceptional visual acuity up to 30 times sharper than humans, enabling prey detection from considerable distances. Birds possess tetrachromatic vision—four cone types including UV-sensitive receptors around 360–373 nm—allowing color discrimination you can’t even imagine. This UV vision helps locate fruits, insects, and even urine trails left by small mammals.

Meanwhile, olfactory foraging plays a surprisingly important role in specific groups: semi-aquatic birds and nocturnal species show enlarged olfactory bulbs, compensating for limited visibility with scent-based navigation.

Multisensory integration combines these senses, with seabirds tracking food across vast oceanic distances through smell while raptors rely almost exclusively on their striking eyesight for hunting success.

Sunbirds Learning Human Routines

Beyond instinct, sunbirds demonstrate remarkable cognitive flexibility in urban nesting areas, synchronizing their nectar-feeding patterns with your daily schedule. These specialized feeders adjust foraging times to avoid peak human activity—usually before 8 a.m. and after 6 p.m.—showing temporal synchronization that improves chick survival by up to 27%.

You’ll notice their spatial learning as they return to the same verandas or clotheslines season after season, using landmarks like bicycles for navigation. This predator avoidance strategy works: nest success rates near human dwellings reach 68–75%, as cats and owls avoid occupied spaces, making your routine their survival advantage.

Wild Birds’ Weight Management

Wild birds maintain nearly constant body mass through advanced energy regulation, even when high-quality food is abundant. Research on Red Knots shows they deliberately increase activity and reduce consumption when offered calorie-dense diets, preventing obesity that would compromise flight efficiency and increase predation risk. You’ll notice their weight management relies on:

- Energy Regulation – balancing intake with expenditure through activity modulation

- Metabolic Demands – burning calories at rates 10 times their basal metabolism during migration

- Seasonal Adjustments – building controlled fat reserves for winter survival or long-distance travel

- Behavioral Adaptations – increasing foraging activity in resource-rich periods to prevent overconsumption

- Dietary Influence – selecting nutrient-dense wild foods like insects and seeds over empty calories

This avian nutrition strategy ensures ideal wild bird weight management, with their high metabolism and natural feeding habits creating a self-regulating system mammals rarely achieve.

Bird Species Diets

When you look at specific bird species, you’ll notice their diets reflect striking adaptations to their environments and lifestyles. From waterfowl dabbling in shallow waters to specialized feeders with unique techniques, each group has evolved distinct feeding strategies.

Here’s a closer look at how different bird species meet their nutritional needs throughout the year.

Waterfowl and Shorebirds

Waterfowl and shorebirds exhibit striking diet variability, with waterfowl diets shifting dramatically between seasons. During winter, their diet consists of 60–80% plant material for energy, while the breeding season demands up to 70% aquatic invertebrates for protein and calcium. Mallards, for instance, require 19.6% protein during egg production, sourcing it from invertebrates like Gammarus (48% protein) and blue mussels (16% protein).

Shorebird feeding relies heavily on invertebrate abundance during migration, with probing depths varying by species. Whimbrels can reach depths of 41 mm, while Common Redshanks probe up to 33 mm. Waterfowl bill adaptations enable specialized feeding techniques—dabbling ducks filter surface vegetation, while diving species pursue deeper prey.

| Waterfowl Diet Component | Nutritional Value (DMB) |

|---|---|

| Whirligig beetles | 28% protein |

| Barnyardgrass seeds | 62–68% carbohydrates |

| Pondweed | 73–85% carbohydrates |

| Duckweed | 60% carbohydrates, 11% fat |

Waterfowl nutrition depends on complementary habitats. Agricultural fields provide energy-rich grains, while wetlands supply essential amino acids through invertebrates. This supports the 1.94 pounds of daily food intake required by wintering ducks.

Songbirds

Songbirds rank among nature’s most adaptable eaters, with insects forming at least 60% of nestling diets during spring and summer, providing essential insect protein for growth. These insectivorous birds switch to seed preference when temperatures drop, with black oil sunflower seeds attracting 70% of North American feeder visitors due to high energy content.

Winter suet becomes critical for survival, supporting nearly half of documented feeder species through harsh conditions. Understanding songbird diets directly impacts songbird conservation efforts, as feeding behaviors shift dramatically with seasonal changes.

Migratory species consume up to four times their body mass in fruit calories daily during autumn migration, while non-migratory residents rely heavily on your well-stocked feeders to bridge food gaps.

Specialized Feeders

Specialized feeders demonstrate nature’s precision through striking beak morphology and tongue adaptations. You’ll find these structural modifications enable highly efficient resource exploitation. Consider the following examples:

- Hummingbirds oscillate brush-tipped tongues 15-20 times per second to extract nectar from deep corollas

- Flamingos employ filter feeding mechanisms that process up to 20 beakfuls per second, straining crustaceans through lamellae

- Crossbills possess crossed mandibles specifically adapted for extracting seeds from conifer cones

- Woodpeckers extend barbed tongues up to 4 cm beyond their chisel-like beaks to capture insects

- Raptors talons generate grip forces exceeding 400 psi during prey capture

Understanding these adaptations helps you select appropriate bird feeder options and seed types for attracting birds to your garden.

Sapsuckers

Sapsuckers aren’t your typical woodpeckers—they’ve mastered the art of tapping trees like tiny arborists with a sweet tooth. You’ll recognize yellow-bellied and red-breasted sapsuckers by their methodical drilling patterns, creating shallow rectangular or circular wells that access sap reservoirs in over 1,000 tree species, particularly birches and maples with high sugar content. Tree sap comprises 20-100% of their diet depending on season, peaking between April and mid-July when sugar maples flow abundantly.

- Sapsuckers drill "orchard trees," maintaining just two or three active feeding sites with regular well maintenance

- Their brush-like tongues collect flowing sap rather than sucking it directly from phloem and xylem layers

- Insect populations increase dramatically around sap wells, providing essential insect supplement during nesting seasons when protein needs surge to 50% of total intake

- Over 35 bird species, including ruby-throated hummingbirds seeking nectar alternatives, benefit from these communal feeding stations

- Their ecological role extends beyond personal nutrition, creating foraging opportunities for squirrels, porcupines, and diverse insect populations

Hummingbirds

You’ll find hummingbirds among the most notable nectar-feeding birds, consuming 60–80% insects and spiders for protein, with nectar supplying rapid sugar-based energy. Their metabolism rates—exceeding 75 times that of humans—drive exceptional feeding requirements, with individuals eating up to twice their body weight daily and visiting flowers every 10–15 minutes.

These aerial specialists prefer nectar concentrations around 20% sucrose, matching natural flower nectar, though they’ll adjust sugar preference to 25–30% concentrations before migration to build fat reserves.

Beyond their insect consumption benefiting pest control, their pollination role proves essential across the Americas, making native flowering plants more valuable than nectar feeders alone for sustaining populations.

Flamingos

Unlike hummingbirds, which chase nectar from blossoms, flamingos turn to algae-rich waters, employing filter feeding mechanisms that set them apart among avian diets. Their specialized bills contain comb-like lamellae acting as filtration sieves, separating microorganisms through rapid head-sweeping motions at up to four cycles per second. You’ll observe their diet composition driving pigment metabolism through carotenoids like beta-carotene and astaxanthin, which create characteristic pink plumage.

- Lesser flamingos consume approximately 70 g daily of Spirulina platensis microalgae for protein and pigmentation

- Brine shrimp (Artemia salina) and diatoms supplement dietary adaptations based on habitat influence

- Captive feeding protocols require carotenoid-enriched formulations to maintain coloration and reproductive health

Their dietary specialization reflects striking evolutionary refinement in bird feeding strategies.

Oxpeckers

Oxpeckers exemplify complex avian-mammal relationships within African savannas, combining parasite consumption with facultative wound feeding that challenges traditional mutualistic classifications. Their ecological impact places them between helpful insectivores and opportunistic parasites.

Yellow-billed oxpeckers (Buphagus africanus) consume up to 13,600 tick larvae daily, while red-billed species (B. erythrorhynchus) exploit broader host preferences, including buffalo, giraffe, and cattle. Dietary preferences shift seasonally; when tick availability decreases, wound-feeding rates increase considerably, sometimes delaying host tissue recovery.

Conservation status remains "Least Concern," though livestock pesticide use threatens food availability.

| Diet Component | Daily Intake | Behavioral Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tick larvae | Up to 13,600 items | Primary food source during peak parasite seasons |

| Engorged adult ticks | 109 Boophilus females | High-energy targets when available |

| Mammalian blood/tissue | Variable, increases when ticks scarce | Facultative wound-feeding behavior documented |

| Mixed arthropods | Higher in red-billed species | Includes mites, flies, insect larvae |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Do birds remember you if you feed them?

Imagine this: a crow watching from a power line as you refill the feeder each morning, then arriving precisely five minutes after you step inside. Birds like crows, chickadees, and magpies can recognize your face and voice for months, even years.

They pick up on visual cues and vocal signatures, linking you to food through habituation effects. With memory duration extending up to 285 days in some species, feeding wild birds regularly means you’re not just supporting backyard birds—you’re building a relationship where they remember exactly who keeps their feeding station stocked.

Will all birds eat meat?

No, not all birds eat meat—dietary strategies vary widely across species. Approximately 12-20% are omnivores, 30-35% are herbivorous (consuming seeds, fruits, and nectar exclusively), and only 15-20% are carnivores.

While raptors, owls, and gulls actively hunt prey, finches, hummingbirds, and parrots thrive on plant-based diets, demonstrating that the avian dietary spectrum ranges from strict herbivores to hypercarnivorous predators.

Most species occupy insectivorous or omnivorous niches, depending on seasonal availability and habitat resources.

What food can I give wild birds?

Think of feeding wild birds like stocking a pantry—you’ll want safe seed mixes like nyjer and black-oil sunflower seed, homemade suet for winter energy, plus mealworms and fruit options during warmer months.

Avoid bread, chocolate, avocado, and onions, which can seriously harm them.

Can birds eat rice or pasta safely?

You can safely offer plain, cooked rice and pasta to wild birds as occasional treats, since both provide easily digestible carbohydrates that support energy needs during extreme weather.

The myth that uncooked rice causes harm has been thoroughly debunked by ornithologists, though you’ll want to skip any seasoning, oils, or sauces to protect avian health.

Do birds eat nuts like almonds or walnuts?

Most woodland species readily consume unsalted, raw almonds and walnuts, which deliver essential fatty acids, protein, and minerals like calcium and magnesium. These high-energy nuts support woodpeckers, jays, nuthatches, and chickadees during winter and breeding seasons.

Though you’ll need to offer them chopped and unsalted to prevent choking or salt toxicity.

How does diet affect bird plumage color?

What you feed your bird is like a paintbrush for its feathers. Carotenoid intake from berries, insects, or seeds creates those vibrant reds, oranges, and yellows you’ll admire in cardinal plumage or goldfinch wings, while protein-rich bird diets guarantee proper feather growth and structural colors, including iridescent sheens.

Nutritional stress weakens feather integrity, dulling even the most striking hues.

Can birds eat spicy peppers like chili?

Birds can eat spicy peppers without any discomfort because they lack TRPV1 receptors that respond to capsaicin, the compound responsible for heat in chilies. This adaptation aids seed dispersal, as birds consume and distribute pepper seeds effectively.

You can even use capsaicin-treated seed as a squirrel deterrent in feeders, and wild consumption of hot peppers is well-documented across numerous bird species diets and dietary preferences.

What foods help improve birds’ immune systems?

You’ll strengthen your bird’s immune system by offering antioxidant-rich foods like berries, dark leafy greens, and seeds.

These natural food sources provide vitamin supplementation and mineral importance through nutrients like vitamins A, C, and E, plus zinc and selenium, which improve avian nutrition and support gut microbiome health for best immune function.

Do birds need different foods when molting?

As the saying goes, you can’t build a house without solid materials—and during molting, you can’t grow quality feathers without the right fuel.

Yes, birds need different foods when molting, specifically diets higher in protein (20-25% crude protein) and energy-rich options like mealworms, insects, and high-fat seeds such as sunflower to support intensive feather growth, increased metabolic rates, and the demanding keratin synthesis process.

How often should I clean bird feeders?

You’ll want to clean your bird feeders every one to two weeks during typical conditions, but ramp up to weekly during wet weather or heavy bird traffic.

This bird feeder maintenance prevents pathogen risks like salmonella and aspergillosis, keeping your bird feeding practices safe and your visitors healthy year-round.

Conclusion

Just as Darwin observed finches adapting beaks to their island ecosystems, understanding what different birds eat transforms your backyard into a living laboratory of ecological relationships.

Each seed you scatter, feeder you hang, or native plant you cultivate becomes part of a deliberate conservation strategy—one that honors the millennia of adaptation encoded in every beak shape and hunting technique.

Your informed choices directly shape which species thrive in your local habitat.

- https://birdatlas.co.nz/classification-of-birds-by-diet/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-021-01049-9

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6061143/

- https://www.vims.edu/bayinfo/ospreycam/about/diet/

- https://bioone.org/journals/ornithological-applications/volume-114/issue-1/cond.2012.110043/Effects-of-Nutritional-and-Anti-Nutritional-Properties-of-Seeds-on/10.1525/cond.2012.110043.short