This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

If you’ve ever heard a rhythmic tapping echoing through California’s oak woodlands, you’ve probably caught one of the state’s nine woodpecker species hard at work. These birds aren’t just making noise—they’re drilling for insects, carving out nest cavities, and even storing thousands of acorns in “granary trees” like feathered squirrels with power tools.

From the crow-sized Pileated Woodpecker with its striking red crest to the sparrow-sized Downy that visits backyard feeders, California’s woodpeckers range from common suburban visitors to specialized species that thrive only in recently burned forests.

Learning to identify them opens up a whole new dimension of birdwatching, where size, plumage patterns, and distinctive drumming rhythms tell you exactly who’s pecking away in the trees above.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Common Woodpecker Species in California

- How to Identify California Woodpeckers

- Habitats and Range Across California

- Woodpecker Behaviors and Diets

- Conservation and Ecological Importance

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- How many types of Woodpeckers are there in California?

- Where do pileated woodpeckers live in California?

- Are hairy woodpeckers common in California?

- Which is the largest woodpecker in California?

- Are spotted woodpeckers common in California?

- Are black backed woodpeckers common in California?

- What is the most common woodpecker in California?

- Is it good to have Woodpeckers in your yard?

- How do you tell the difference between a Downy Woodpecker and a hairy woodpecker?

- Are Nuttall’s Woodpeckers rare?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- California hosts nine distinct woodpecker species ranging from the sparrow-sized Downy Woodpecker to the crow-sized Pileated, each occupying specific ecological niches from suburban backyards to post-fire habitats.

- Acorn Woodpeckers create “granary trees,” storing up to 50,000 acorns in custom-drilled holes, functioning as cooperative breeding groups that inadvertently support forest regeneration through seed dispersal.

- Woodpeckers serve as ecosystem engineers by excavating cavities used by over 80 secondary nesting species, controlling pest populations, and indicating forest health—particularly the Black-backed Woodpecker in burned areas.

- Conservation challenges include habitat loss from post-fire salvage logging (leaving only 161-300 Black-backed Woodpecker breeding pairs statewide), climate-driven range contractions projected at 53% by 2080, and pesticide-related food depletion.

Common Woodpecker Species in California

California is home to nine woodpecker species, each with its own personality and quirks. You’ll find everything from the tiny Downy Woodpecker to the crow-sized Pileated Woodpecker drumming through the state’s diverse landscapes.

Let’s meet each species and learn what makes them special.

Downy Woodpecker

The Downy Woodpecker is California’s tiniest native woodpecker—just 6–7 inches long and about an ounce. You’ll spot these black-and-white beauties in backyard habitats and urban areas, where their size advantage lets them forage on delicate branches.

Key identification features include:

- Males sport bright red crowns

- Diet consists mainly of insects and seeds

- Populations are currently threatened by rising temperatures

Their adaptability makes woodpecker identification easier for beginners, and their small size helps them forage.

Hairy Woodpecker

Moving from tiny to tall, the Hairy Woodpecker is a classic fixture in California’s forests. For Hairy identification, look for a sturdy, black-and-white bird with a long, chisel-like bill. Their foraging behavior includes hunting insects deep in bark. Diet variations span seeds, fruits, and insects.

This woodpecker species remains common, highlighting the lasting importance of forest habitat. They also play a key role as ecosystem engineers by creating cavities.

Northern Flicker

While most woodpeckers of California cling to bark, the Northern Flicker breaks the mold with ground foraging habits—you’ll spot them hunting ants on lawns.

Woodpecker identification here centers on that red mustache stripe (in western states) and brown-barred back. Despite urban adaptation success, populations face a concerning decline of roughly 49% since 1966.

Their woodpecker behavior and habitat flexibility make them backyard favorites.

Pileated Woodpecker

Unlike the ground-loving flicker, California’s largest resident woodpecker demands mature forests. The Pileated Woodpecker carves rectangular cavities in dead trees, functioning as a forest indicator of old-growth health. You’ll recognize its crow-sized frame and striking red crest immediately. Though less common, it’s regularly spotted in specific reserves:

- Found in montane conifer forests

- Creates cavities used by 80+ species

- Targets carpenter ants and beetle larvae

- Prefers established woodland over urban areas

Acorn Woodpecker

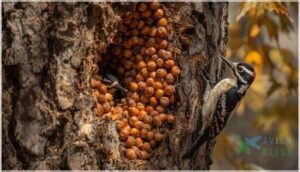

One of California’s most charismatic woodpecker species, the Acorn Woodpecker, thrives in oak woodlands, where communal groups store thousands of acorns in granary trees.

These social birds drill precise holes in trunks and poles, creating impressive acorn granaries that sustain families year-round.

Their habitat dependence makes them vulnerable to oak conservation challenges and climate impacts, yet populations remain stable where valley oaks persist.

Nuttall’s Woodpecker

A California near-endemic, Nuttall’s Woodpecker inhabits oak woodlands and riparian corridors throughout the state. You’ll spot this striking species by its black, brown, and white plumage, with males displaying red crowns.

Despite its restricted range, the population has grown about 0.8% annually since 1966. Look for these birds foraging for insects and ants along mature tree trunks and branches.

Lewis’s Woodpecker

With its unique green back and pink body, Lewis’s Woodpecker stands out among California’s woodpecker species in this identification guide. You’ll find this less common resident in open pine-oak and burned forest habitats across northern California, where fire ecology shapes its habitat preferences.

Conservation status remains relatively stable, though its unique behaviors—including flycatching for insects—make it a special sighting in the state’s natural history.

Red-breasted Sapsucker

Ever spotted neat rows of tiny holes in tree bark and wondered who’s behind the artwork? Meet the Red-breasted Sapsucker—a specialist among western sapsuckers. This bird drills Sapsucker Sap Wells along California’s coastal forests.

Look for:

- vivid red heads and throats

- black-and-white wings

- preference for riparian habitats

- subtle hybridization with nearby species

A marvel of woodpecker identification!

Black-backed Woodpecker

If burned forests were a restaurant, the Black-backed Woodpecker would be the only customer. This specialist thrives in post-fire habitat, hunting beetle larvae in charred trees—an essential role in forest recovery.

Despite its ecological importance, habitat destruction from salvage logging threatens its persistence. Look for its solid black back and yellow crown patch, hallmarks of this noteworthy woodpecker species in California’s recovering landscapes.

How to Identify California Woodpeckers

Spotting woodpeckers in California gets easier once you know what to look for. Each species has its own mix of field marks—from size and color patterns to the sounds they make while drumming on trees. Here’s how to tell them apart in the field.

Size and Shape Differences

You’ll notice size and shape are your best friends for woodpecker identification—and these California birds range dramatically. Here’s what to look for regarding physical description of birds:

- Body length: Downy Woodpeckers measure just 14–18 cm versus the Pileated’s impressive 40–48 cm

- Mass variation: From the Downy’s 21–28 g to the Pileated’s hefty 250–400 g

- Wingspan range: Spans 25–30 cm (Downy) to 66–76 cm (Pileated)

- Bill shape: Short and dainty (Downy) versus chisel-like and strong (Hairy)

- Tail proportions: Compact on smaller species, extensive on larger ones

These bird characteristics make woodpecker species identification surprisingly straightforward once you start bird size comparison.

Plumage Patterns and Colors

Once you’ve nailed size differences, plumage patterns and colors seal the deal. Downy Woodpeckers show classic black-and-white patterns with males sporting that red head spot—while western birds appear darker and dingier.

Northern Flickers flash their white rump in flight, and males have that red mustache stripe.

Acorn Woodpeckers? They’re unmistakable with bold red caps and striking white facial patches used for social signaling.

Distinctive Calls and Drumming

Beyond color, woodpecker vocalizations and calls give you acoustic identification superpowers. Hairy Woodpeckers drum faster—about 26 beats per second—while Downys hit 17. Pileated Woodpeckers deliver that unmistakable loud “kuk-kuk-kuk” call. Nuttall’s Woodpeckers rattle with 14–45 rapid pit notes, mainly October through May.

These territorial signals and temporal patterns in bird calls reveal not just species, but breeding season activity and drumming mechanics tied to woodpecker behavior and adaptations.

Male Vs. Female Characteristics

Once you’ve got calls down, plumage differences help you separate males from females. Males generally sport a red patch on the head—look for it on the nape in Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers, or the “moustache” in Northern Flickers. Females lack these red markings entirely. Despite this visual split, size dimorphism is minimal across California woodpecker species, and both sexes share nesting roles and territory defense equally. Bird identification gets easier when you know what to spot:

- Male Acorn Woodpeckers have solid red caps; females show a black forehead band

- Downy and Hairy males display red nape patches absent in females

- Northern Flicker males flash red moustache stripes; females don’t

- Nuttall’s males feature rear crown red patches missing on females

- Survival rates show no sex bias across species

Habitats and Range Across California

California’s woodpeckers aren’t picky about where they set up shop—you’ll find them everywhere from dense oak forests to your suburban backyard. Each species has carved out its own niche, choosing habitats that match their foraging style and food preferences.

Let’s explore the main environments where you’re most likely to spot these busy birds across the state.

Oak Woodlands and Forests

You’ll find California’s oak woodlands buzzing with woodpecker life, particularly where oak abundance and habitat heterogeneity run high. Acorn Woodpeckers dominate these landscapes, their acorn caching behavior transforming telephone poles and mature oaks into living pantries holding up to 50,000 acorns.

Nuttall’s Woodpeckers also thrive here, gleaning insects from bark while supporting woodland regeneration—though oak pathogens and drought increasingly threaten these critical woodpecker habitats.

Riparian and Riverside Areas

Along California’s riparian woodlands, you’ll discover Downy and Nuttall’s Woodpeckers thriving in cottonwood and willow corridors. These habitats offer prime nesting sites and abundant insect prey—insects comprise roughly 75–80% of riparian diets here.

Conservation initiatives like the Western Riverside MSHCP now protect over 34,000 acres, addressing population trends threatened by water diversion and habitat loss affecting woodpecker foraging and breeding success.

Urban and Suburban Environments

In California’s cities and suburbs, you’ll find woodpeckers adapting to human-modified landscapes—though species richness drops compared to wildlands. Acorn Woodpeckers lead urban adaptation, nesting in utility poles and storing acorns in backyard oaks. Birdwatching reveals fascinating habitat shifts:

- Woodland patches over 1 hectare support most species

- Urban foraging changes include visits to bird feeders

- Conservation efforts prioritize preserving multi-layered tree corridors

Larger patches maintain healthier populations and more diverse bird behavior.

Burned Forests and Post-fire Habitats

Within five years after wildfire, blackbacked woodpeckers flock to burnt trees where snag density peaks—study sites showed occupancy around 0.65 in Sierra Nevada fires. Species occupancy drops as fire age increases and snags decay.

Post-fire management and habitat restoration now prioritize retaining large snags, recognizing the role of fire in ecosystems and these postfire ecosystems’ value to specialized cavity-nesters.

Woodpecker Behaviors and Diets

Woodpeckers aren’t just tree-drummers—they’re resourceful foragers with some pretty clever survival strategies. From probing bark for hidden insects to stockpiling thousands of acorns, each species has adapted unique ways to find and store food.

You’ll also notice differences in their nesting habits, social structures, and seasonal patterns across California’s diverse landscapes.

Foraging Techniques and Food Sources

You’ll notice that different woodpeckers have distinct foraging styles to match their prey. Bark gleaning dominates in species like Nuttall’s and Downy Woodpeckers, where insects are plucked from crevices. Northern Flickers prefer ground foraging, consuming thousands of ants per session. Lewis’s Woodpecker uses aerial hawking, catching insects mid-flight.

Supplemental feeding at backyard suet feeders sustains urban populations, while microhabitat selection ensures each species finds its preferred insects and acorns efficiently.

Acorn Storage and Caching

Acorn Woodpeckers create something extraordinary: granary trees can hold up to 50,000 acorns, each snugly wedged in custom-drilled holes.

Acorn Woodpeckers create granary trees that can hold up to 50,000 acorns, each wedged in custom-drilled holes

Seasonal acorn storage peaks in autumn when oak crops mature, and caching group structure involves 5-15 birds cooperating across territories of up to 9 hectares.

These ecological storage impacts support woodland regeneration—cached acorns inadvertently plant future forests while providing critical winter food security.

Nesting and Social Behavior

Ever wonder how woodpeckers raise families together? Many species practice cooperative breeding—think of it as a multi-generational household. Acorn Woodpeckers form groups with multiple breeders sharing nest duties, while cavity nesting allows both parents to excavate homes and provision young.

Reproductive timing peaks around mid-nestling stages, intensifying feeding demands. This social structure strengthens group dynamics through shared territory defense and communal care, creating resilient communities across California’s oak woodlands and forests.

Seasonal Movements and Migration

While some woodpeckers stay put year-round, others shift with the seasons. Here’s what drives their movement patterns:

- Irruptive movements — Lewis’s Woodpeckers show dramatic year-to-year swings, arriving mid-September to early October depending on food availability.

- Elevational shifts — Acorn Woodpeckers move upslope in fall; Red-breasted Sapsuckers winter from sea level to 6,000 feet.

- Site fidelity — Many return to traditional territories annually, though acorn crop failures can force temporary dispersal.

Food resources ultimately dictate their range and migration timing.

Conservation and Ecological Importance

Woodpeckers do more than just make noise in the trees—they’re key players in California’s ecosystems. But these birds face real threats, from habitat loss to the way we manage our forests.

Let’s look at what’s putting woodpeckers at risk, how they help the environment, and what we can all do to protect them.

Threats to Woodpecker Populations

Despite California’s woodpecker diversity, environmental challenges threaten their survival. Habitat loss from post-fire logging has left black-backed woodpeckers with only 161 to 300 breeding pairs statewide. Climate impacts project a 53% range contraction by 2080, while pesticide exposure reduces food sources.

Here’s what’s happening:

| Threat Category | Primary Impact | Species Most Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat Fragmentation | Nesting site loss | Black-backed, Nuttall’s |

| Climate Impacts | Range reduction | All California species |

| Fire Management | Deadwood removal | Black-backed, Pileated |

| Pesticide Exposure | Food depletion | Downy, Acorn |

| Predation Pressures | Nest failure rates | Urban-dwelling species |

Understanding these conservation challenges helps you appreciate why protecting woodpecker populations matters for California’s forests.

Woodpeckers as Ecosystem Engineers

Beyond facing serious threats, these birds play an important role you mightn’t expect. Through cavity creation, woodpeckers support over 80 secondary nesters—birds and mammals relying on abandoned holes. Their ecological importance extends further:

- Forest regeneration: Acorn storage disperses thousands of seeds annually

- Pest controllers: Black-backed species target destructive beetle larvae in burned areas

- Food resources: Excavation sites attract insectivorous species, strengthening trophic impacts across California’s forests

Conservation Programs in California

California responds through targeted wildlife conservation initiatives. The Western Riverside County MSHCP protects 34,080 acres of riparian and woodland habitat for species like the Downy Woodpecker.

Meanwhile, burned forests receive special attention: the Institute for Bird Populations partners with federal agencies on monitoring programs that make post-fire management compatible with Black-backed Woodpecker needs.

Oak Woodland Bird Conservation Plans guide sustainable forestry and habitat conservation statewide.

How to Support Local Woodpeckers

You can create wildlife habitats right in your backyard through native plantings like Coast Live Oak and Manzanita, which boost food availability by up to 40%.

Nest boxes offset habitat loss where mature trees have declined by 90%. Support community initiatives monitoring local populations, or practice snag preservation by leaving dead trees standing.

These habitat restoration efforts increase woodpecker nesting success substantially through attracting woodpeckers to your yard with proper habitat preservation and restoration for woodpecker conservation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many types of Woodpeckers are there in California?

You’ll find a remarkable 15 distinct woodpecker species calling California home as of 2023, including both Sapsuckers and Flickers—making the state a true paradise for anyone passionate about woodpecker diversity.

Where do pileated woodpeckers live in California?

You’ll spot pileated woodpeckers in mature coniferous forests throughout the Sierra Nevada and coastal forests, mostly above 1,000 meters elevation.

Habitat fragmentation limits their range, though some recent range expansion into higher-elevation national forests has occurred.

Are hairy woodpeckers common in California?

You’ll find Hairy Woodpeckers fairly common in California’s mountain forests and riparian woodlands, though habitat fragmentation makes them scarce in coastal southern regions, deserts, and valleys.

Snag density strongly influences their local population trends and breeding patterns.

Which is the largest woodpecker in California?

The Pileated Woodpecker takes the crown as the largest woodpecker species you’ll find here, measuring up to 19 inches long—roughly crow-sized—with distinctive red crests and powerful excavating bills.

Are spotted woodpeckers common in California?

The Great Spotted Woodpecker isn’t found in California. However, the Ladder-backed Woodpecker—sometimes called “spotted” for its marked flanks—thrives in southeastern desert regions.

Nuttall’s Woodpecker, exclusive to California, shows barred patterns but isn’t classified as spotted scientifically.

Are black backed woodpeckers common in California?

Black-backed woodpeckers are rare, with only 161 to 300 breeding pairs statewide. They are concentrated in Sierra Nevada forests above 6,000 feet.

Their fire dependency makes their conservation status precarious. Post-fire salvage logging remains their greatest threat.

What is the most common woodpecker in California?

The Downy Woodpecker is California’s most common species. Its small size lets it forage on delicate branches where larger woodpeckers can’t reach.

You’ll spot them frequently in backyards, urban areas, and oak woodlands throughout the state, making identification easier for beginners.

Is it good to have Woodpeckers in your yard?

Here’s the honest answer: woodpeckers bring real benefits to your yard. They’re natural pest control experts, consuming beetles and grubs that damage trees.

They support biodiversity and soil health. The trade-off? Minor structural damage sometimes occurs, but regulatory protections and non-lethal deterrents help manage this.

How do you tell the difference between a Downy Woodpecker and a hairy woodpecker?

You can tell these species apart by checking their bill size and tail feathers. Hairy Woodpeckers have much longer bills.

Hairy birds show pure white outer feathers, while Downy ones display black spots or barring.

Are Nuttall’s Woodpeckers rare?

Nuttall’s Woodpecker isn’t rare within California—population stability remains strong, with over 100,000 individuals statewide. Range restriction limits them almost exclusively to California, though suburban adaptation and habitat specificity support their conservation status as “Least Concern.

Conclusion

Whether you’re watching a Downy drill into deadwood or spotting an Acorn Woodpecker stuffing its granary, California’s woodpeckers offer endless fascination once you know what to look for.

With nine species spanning diverse habitats—from suburban backyards to remote burned forests—these birds shape ecosystems in significant ways.

Keep your binoculars ready, tune into those drumming rhythms, and you’ll discover that identifying woodpeckers of California transforms every woodland walk into an adventure worth taking.

- https://www.animalspot.net/woodpeckers-in-us/california-woodpeckers

- https://birdwatchingcentral.com/woodpeckers-in-california/

- https://www.wrc-rca.org/the-downy-woodpecker-pecks-in-western-riverside-county/

- https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/birds/black-backed_woodpecker/pdfs/BBWO-CESA-petition.pdf

- https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjfr-2015-0035