This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

You’ll find an impressive range of herons in Pennsylvania, from the towering Great Blue Heron to the secretive Least Bittern.

You’ll find an impressive range of herons in Pennsylvania, from the towering Great Blue Heron to the secretive Least Bittern.

These wading birds love wetlands, marshes, and even quiet ponds, where they hunt fish with a precision that’d make a fisherman jealous.

Some, like the Green Heron, are small and quick, while others, like the Great Egret, seem almost regal with their snowy white feathers.

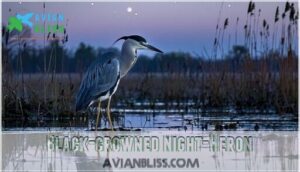

Keep an eye out at dawn or dusk for the Black-crowned Night-Heron, a true night owl of the heron world.

Wondering who visits Pennsylvania most often? There’s a lot more to uncover about these elegant creatures!

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Great Blue Heron

- American Bittern

- Black-crowned Night-Heron

- Green Heron

- Great Egret

- Cattle Egret

- Snowy Egret

- Least Bittern

- Yellow-crowned Night-Heron

- Other Water Birds in Pennsylvania

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What kind of herons are in PA?

- Did I see a crane or a heron?

- What is the difference between a heron and an egret?

- Is there a difference between a great blue heron and a blue heron?

- What are the main predators of Pennsylvania herons?

- How do herons communicate during nesting periods?

- How do herons select mates during breeding season?

- What challenges do herons face during migration?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- You’ll find 9 heron species in Pennsylvania, including the Great Blue Heron, Green Heron, and elusive Least Bittern, thriving in wetlands, marshes, and ponds.

- Each heron species has unique traits, like the nocturnal habits of the Black-crowned Night-Heron or the bait-fishing skill of the Green Heron.

- Conservation efforts are vital, as habitat loss threatens several species like the American Bittern and Snowy Egret, despite the Great Blue Heron’s stable population.

- Identifying herons gets easier when you know their features—like the Great Egret’s striking white plumage or the Snowy Egret’s yellow feet—making wetlands ideal for birdwatching.

Great Blue Heron

You’ll instantly recognize Pennsylvania’s most common heron by its impressive size and blue-gray feathers that seem to blend perfectly with cloudy skies.

Pennsylvania’s great blue heron, with its striking blue-gray feathers and six-foot wingspan, embodies the elegance of the state’s wetlands.

This four-foot-tall giant can stretch its wings to nearly six feet wide, making it hard to miss when it’s hunting fish along your favorite lake or river.

Appearance and Habitat

Spotting Pennsylvania’s most recognizable heron becomes easier when you know what to look for. This magnificent bird stands nearly four feet tall with striking plumage variations that make identification straightforward.

- Blue-gray body with distinctive black crown stripe extending over bright yellow eyes

- Massive wingspan reaching six feet, creating an impressive silhouette against Pennsylvania wetlands

- Long, dagger-like yellow bill perfectly designed for spearing fish and frogs

Great blue herons show remarkable wetland dependency, thriving in marshes, rivers, and lakeshores across Pennsylvania heron species habitats.

You can even find heron-themed merchandise online.

Their camouflage adaptations help them blend seamlessly into wetland environments, making patient observation essential for successful sightings.

Range and Distribution

Great blue herons call Pennsylvania home year-round, making them the state’s most common heron species.

You’ll spot these majestic birds from Philadelphia’s urban waterways to the Allegheny Mountains’ remote streams.

Their heron range spans every county, with the highest population density concentrated around major water bodies like Lake Erie and the Delaware River.

| Region | Seasonal Presence | Habitat Preference |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern PA | Year-round residents | Rivers, urban wetlands |

| Central PA | Breeding strongholds | Farm ponds, reservoirs |

| Western PA | Migration corridors | Lake shores, marshes |

Climate change hasn’t substantially altered their migration patterns yet.

Conservation status remains stable thanks to protected wetlands supporting Pennsylvania bird species.

Habitat specificity varies widely—they’re equally comfortable in city parks and wilderness areas.

YouTube Channel for Great Blue Heron

Experience Great Blue Heron life through dedicated Heron Cam footage that captures Pennsylvania birdwatching moments you’d never see otherwise.

These birdwatching videos showcase seasonal changes and conservation efforts while documenting herons in Pennsylvania’s wetlands.

Watch intimate glimpses of:

- Nesting behavior as parents build stick platforms high in trees

- Feeding habits with patient stalking and lightning-fast strikes

- Chick care from hatching through first flight

American Bittern

Finding American Bitterns requires patience and sharp ears. These Pennsylvania herons master marsh camouflage with their mottled brown plumage, blending seamlessly into reed beds.

When threatened, they freeze with bills pointed skyward, becoming nearly invisible. Their secretive behavior makes sightings rare, but you’ll hear their distinctive "oonk-a-lunk" vocalizations echoing across wetlands during breeding season.

This heron species faces serious habitat loss throughout Pennsylvania. Their conservation status reflects declining wetland environments they depend on. American Bitterns need extensive emergent vegetation for nesting and hunting fish, frogs, and insects.

These stocky birds, measuring 23-33 inches long, represent important indicators of healthy heron habitat. Listen carefully in freshwater marshes—their booming calls often provide your only clue to their presence. Bitterns, like the dippers’ habitat needs, are impacted by habitat degradation.

Black-crowned Night-Heron

Black-crowned Night-Heron’s distinctive appearance makes identification straightforward among herons in Pennsylvania.

You’ll recognize this stocky, medium-sized bird by its jet-black cap contrasting sharply with gray wings and white underparts.

Red eyes gleam during twilight hours when these Pennsylvania birds become most active.

Their nocturnal behavior sets them apart from other heron species you might encounter during daytime birdwatching.

While Great Blue Herons hunt openly, Black-crowned Night-Herons prefer dawn and dusk foraging sessions.

Physical adaptations like excellent low-light vision help them catch fish, frogs, and crayfish in dim conditions.

Colony nesting occurs in trees near wetlands, where their harsh "quawk" calls echo through breeding sites.

Though they’re the most widespread heron globally with impressive global distribution, their conservation status in Pennsylvania remains concerning.

Listed as state endangered, habitat loss threatens local populations.

You’ll find them year-round in eastern Pennsylvania, though they’re summer visitors elsewhere in the state.

Green Heron

Pennsylvania’s smallest heron surprises birdwatchers with its remarkable Tool Use abilities.

You’ll spot Green Herons crouched along pond edges, dropping insects as Bait Fishing lures.

Their deep green crown and chestnut neck make identification easy among herons in Pennsylvania.

Listen for their distinctive "skeow" Unique Call echoing from dense vegetation.

These clever hunters prefer secluded heron habitats with thick cover.

Unfortunately, Habitat Loss threatens their Conservation Status.

When birdwatching in Pennsylvania, patience rewards you with glimpses of this secretive species demonstrating nature’s ingenuity through innovative fishing techniques.

Great Egret

When you spot a majestic white bird with a stout yellow bill stalking through Pennsylvania’s wetlands, you’re likely witnessing a Great Egret in action. This elegant heron species stands over three feet tall and showcases pristine white plumage that makes it unmistakable among Pennsylvania’s water birds.

Great Egrets nearly vanished from North America due to hunting for their prized aigrette plumes in the late 1800s. Their dramatic recovery story led to them becoming the Audubon Symbol, representing successful conservation efforts. Today, their conservation status remains stable thanks to habitat protection.

Here are five key facts about Great Egrets:

- They’re found in both freshwater and saltwater habitats across their extensive habitat range

- Their feeding habits include slowly stalking fish, frogs, and aquatic insects in shallow water

- They nest colonially in trees near water sources, often with other heron species

- Adults develop long, flowing aigrette plumes during breeding season

- They’re considered critically imperiled in Pennsylvania but globally secure

For birdwatching in Pennsylvania enthusiasts, spotting these magnificent birds represents a conservation success story worth celebrating. They’re known for their distinctive foraging strategies, including slow stalking and stand-and-wait ambushes.

Cattle Egret

Unlike the elegant Great Egret, you’ll spot Cattle Egrets hanging around farmland rather than wetlands.

This Pennsylvania heron species breaks the mold by preferring pastures over ponds.

Cattle Egret ID becomes easier when you know where to look.

These medium-sized birds measure 18-22 inches with distinctive orange-buff plumes during breeding season.

You’ll find them perched on livestock or strutting through fields, hunting grasshoppers and flies stirred up by grazing animals.

**Invasive Species?

** Not exactly.

Cattle Egrets naturally expanded their range from Africa, arriving in North America during the 1950s.

Their Habitat Expansion continues today, though they remain uncommon visitors to southeastern Pennsylvania.

Their Diet Composition includes insects, ticks, and small amphibians.

Unlike other heron species, they’ve mastered the art of following cattle for easy meals.

Conservation Status remains stable globally, but Pennsylvania sightings peak during late spring and mid-summer migrations.

This bird species in Pennsylvania showcases remarkable adaptability in heron behavior.

Snowy Egret

You’ll spot Pennsylvania’s most elegant visitor by its striking yellow feet that earned it the nickname "golden slippers." The Snowy Egret stands about two feet tall with pristine white plumage and a slender black bill, making heron identification straightforward when you know what to look for.

Key features for Snowy Egret ID:

- Bright yellow feet contrasting with black legs

- All-white body with yellow patch around dark eyes

- Wispy plumes during breeding season on back and head

- Active foraging behavior, stirring water with feet

These heron species rarely visit Pennsylvania, appearing mainly during fall migration through southern corridors. Their historical range once faced severe threats from plume hunting for women’s hats. Today’s conservation status remains stable, though wetland habitats still need protection. Watch for their distinctive foraging behavior as they dance through shallow waters, using those famous feet to stir up prey.

Least Bittern

Measuring just 11-14 inches, the Least Bittern ranks as Pennsylvania’s smallest heron species.

You’ll struggle to spot these masters of marsh camouflage as they freeze with bills pointed skyward among cattails. Their dark caps and buff-striped backs blend perfectly into wetland habitats.

Listen for their surprising cuckoo-like calls during breeding season—quite loud for such tiny birds!

Unfortunately, their conservation status reflects serious concerns due to habitat loss. These secretive birds need dense freshwater marshes to survive, making wetland protection essential for their future.

Least Bitterns share these habitats with other species like the smallest sandpiper species.

Yellow-crowned Night-Heron

While least bitterns hide in dense reeds, you’ll spot Yellow-crowned Night-Herons in more open wetland areas across Pennsylvania.

These stocky herons showcase distinctive black heads with creamy white cheek patches and bright yellow crown plumes.

Their slate-gray bodies and thick necks make Identification Tips straightforward during birdwatching adventures.

Dietary Habits focus heavily on crustaceans – they’re crab and crayfish specialists who hunt nocturnally in shallow waters.

Their Breeding Behavior peaks from early spring through mid-summer, with colonies typically along coastlines or major rivers.

Unfortunately, their Conservation Status faces challenges due to Habitat Threats like wetland loss and shoreline development.

These Pennsylvania herons need our protection:

- Wetland restoration projects preserve critical feeding grounds

- Reduced pesticide use protects their crustacean prey

- Shoreline development limits threaten nesting colonies

- Citizen science surveys track population changes

- Educational outreach builds community support for wetland habitats

Other Water Birds in Pennsylvania

Beyond the nine main heron species, you’ll occasionally spot two additional water birds that share similar habitats across Pennsylvania’s wetlands.

The Little Blue Heron and Tricolored Heron appear less frequently but offer exciting opportunities for dedicated birdwatchers who know when and where to look, especially for those interested in water birds.

Little Blue Heron

Pennsylvania’s Little Blue Heron undergoes dramatic plumage changes from white juvenile stage to dark slate-blue adults with purple-maroon heads.

This smallest heron species measures just 11-14 inches, making regional sightings rare but exciting for Pennsylvania birdwatching enthusiasts.

You’ll find these stand-and-wait predators foraging behavior in wetlands, though their conservation status remains uncertain.

Watch for their distinctive two-toned bills while heron birdwatching at Pennsylvania birdwatching locations, and be aware of the regional sightings.

Tricolored Heron

You’ll spot tricolored herons as graceful migrants passing through Pennsylvania during spring and fall.

These elegant birds prefer coastal habitat over inland waters, making Tricolored ID challenging for local birdwatchers.

Key identification features include:

- Solitary feeding behavior, avoiding flocks or colonies

- Purple-blue wings contrasting with reddish neck during flight

- Declining heron populations due to southeastern breeding range habitat loss

- Conservation status reflects ongoing environmental pressures

Frequency of Heron Sightings in Pennsylvania

For birdwatchers exploring Pennsylvania, heron sightings are a treat, especially spotting the great blue heron.

With around 10,000 breeding pairs statewide, they prefer large lakes, marshes, and rivers. Other heron populations, like great egrets and green herons, are smaller yet stable.

Wetland conservation is key as habitat loss impacts survival. Many birders equip themselves with essential viewing gear for ideal observation.

| Heron | Seasonal Abundance | Main Habitat | Common Locations | Population Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Blue Heron | Year-round | Wetlands, rivers | Statewide | Stable |

| Great Egret | Fall migration | Shallow waters | Southern counties | Threatened |

| Green Heron | Summer | Dense vegetation | Lakes, ponds | Threatened |

| Black-crowned Night | Dusk/Night | Marshes, forests | Wet coastal areas | Endangered |

| American Bittern | Breeding season | Freshwater marshes | Central Pennsylvania | Endangered |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What kind of herons are in PA?

You might think herons are rare, but Pennsylvania hosts species like the Great Blue Heron, American Bittern, Black-crowned Night-Heron, Green Heron, and Great Egret.

Each thrives in wetlands, showing off unique behaviors and features, particularly in their natural habitats, which is a key aspect of their survival and unique behaviors.

Did I see a crane or a heron?

You probably saw a heron if it had long legs, a slender neck, or a sharp bill.

Cranes are taller, bulkier, and have a straight neck in flight, unlike herons’ curved posture.

What is the difference between a heron and an egret?

Herons and egrets differ mainly in color and size.

Egrets are white with black legs and yellow bills, while herons are often grayish or blueish.

Egrets also grow striking breeding plumes called aigrettes.

Is there a difference between a great blue heron and a blue heron?

The great blue heron and blue heron are the same species, Ardea herodias.

People often shorten the name to "blue heron" for convenience, but scientifically and in behavior, they’re identical, just majestic birds.

What are the main predators of Pennsylvania herons?

Imagine a heron’s peaceful marsh as a survival arena.

Its main predators in Pennsylvania include raccoons, foxes, coyotes, owls, and hawks, all seeking vulnerable nests, eggs, or young herons as easy meals.

How do herons communicate during nesting periods?

During nesting, herons use calls, body movements, and bill clattering to communicate.

Their vocalizations range from soft, guttural croaks to loud squawks, signaling threats, courtship, or interactions with mates, colony members, or chicks, which involves vocalizations.

How do herons select mates during breeding season?

During breeding season, male herons perform elaborate courtship displays like bill snapping, neck stretching, and plume fluffing.

These performances attract females, who choose mates based on the quality of displays and the nesting site offered.

What challenges do herons face during migration?

Herons face weather shifts, habitat loss, and exhaustion during migration.

Storms, fewer wetlands, and finding safe rest stops make the journey tricky.

Hungry predators and competition for food add to their adventure’s challenges.

Conclusion

Did you know Pennsylvania is home to nine heron species, each with unique traits?

From the majestic Great Blue Heron to the elusive Least Bittern, these birds captivate with their hunting skills and striking appearances.

Exploring wetlands, marshes, and ponds can help you spot these elegant creatures in their natural habitat.

Whether you’re observing the nocturnal Black-crowned Night-Heron or the vibrant Green Heron, learning about herons in Pennsylvania deepens your appreciation for these remarkable wading birds.