This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

Florida’s waterways host over 40 species of water birds, from tiny rails hiding in marsh grass to pelicans with six-foot wingspans gliding above the surf. You’ll spot Great Blue Herons standing motionless in shallow ponds, Roseate Spoonbills sweeping their bizarre bills through mud, and Wood Storks probing wetlands with tactile precision.

These birds depend on Florida’s diverse habitats—coastal estuaries, freshwater lakes, and sprawling marshes—many of which face serious threats from development and climate change.

Whether you’re learning to identify your first egret or tracking down a rare species, understanding these birds starts with knowing where they live, what makes each one unique, and why protecting their habitats matters for Florida’s ecological future.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Common Water Birds in Florida

- Water Bird Habitats Across Florida

- Unique Adaptations of Florida Water Birds

- Identification Tips for Florida Water Birds

- Conservation of Florida’s Water Birds

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What kind of birds go underwater in Florida?

- What is the underwater bird in Florida?

- What is the big grey water bird in Florida?

- What is the common water bird?

- What kind of bird swims underwater in Florida?

- What is the loud Florida water bird?

- What is the large white water bird in Florida?

- What is the GREY wading bird in Florida?

- What is the diet of Floridas water birds?

- How do Florida water birds adapt to climate change?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Florida’s water birds face a tough combination of threats—habitat loss from coastal development, altered water flow in wetlands, and climate change impacts like sea-level rise—but restoration efforts like the Everglades project have quadrupled wading bird nests in some areas, proving recovery is possible when we fix water management.

- You can identify water birds by focusing on bill shape (spoonbills have flat spatula tips, herons have dagger-like points, pelicans have massive pouches), plumage color changes through seasons, and behaviors like whether they dive underwater (anhingas, cormorants) or wade in shallows (egrets, ibises).

- Different water birds stick to specific habitats based on their feeding style—herons and egrets dominate freshwater marshes and wetlands, pelicans and terns prefer coastal beaches and estuaries, while ducks and geese spread across lakes and ponds, making location your first clue for identification.

- Citizen science through apps like eBird and Merlin gives you real power to help conservation by reporting sightings, tracking population trends, and contributing data that scientists use to make management decisions for threatened species like the Wood Stork and Roseate Spoonbill.

Common Water Birds in Florida

Florida’s waterways are packed with bird life, from the massive herons standing still as statues to the acrobatic pelicans crashing into the waves. You’ll find 27 species of water birds across the state, each with their own hunting style and habitat preference.

Let’s look at the most common groups you’re likely to spot on your next trip to the coast or wetlands.

Herons and Egrets

You’ll spot six heron species and four egret species throughout Florida’s wetlands and coasts. Great Blue Herons and Great Egrets are the giants you’ll see wading in marshes. These herons, egrets, and bitterns nest in massive colonies on mangrove islands.

Watch for the rare Reddish Egret—fewer than 800 remain in Florida. Their specialized bills make feeding adaptations perfectly suited for catching fish and crustaceans in shallow waters. Herons’ sharp beaks are well-suited for hunting in wetlands.

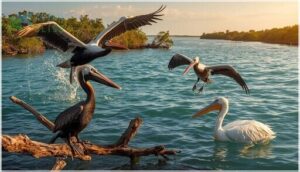

Pelicans and Cormorants

You’ll recognize Brown Pelicans year-round along Florida’s coasts, while American White Pelicans visit in winter. Watch for their different diving techniques—Brown Pelicans plunge from 65 feet high, while Double-crested Cormorants and Anhingas dive from the surface. These Florida water birds often share nesting colonies.

Despite population rebound since the 1960s, over 700 Brown Pelicans still die yearly from entanglement threats with fishing gear. Habitat degradation remains a significant threat to Brown Pelicans.

Ibises, Spoonbills, and Wood Storks

Moving from the pelican family, you’ll find three wading birds with unusual bills: white ibises with downward curves, roseate spoonbills with spatula-shaped tips, and wood storks with thick beaks. These Florida water birds face different futures—wood storks have doubled their breeding population since 1984, while spoonbill nests in Florida Bay dropped from 400 to just 157 recently.

Key Features of Herons, Ibises, and Cranes:

- White Ibises now thrive in urban parks across Palm Beach County, though this shift away from natural wetlands may affect their breeding success

- Roseate Spoonbills are moving inland as sea-level rise makes coastal waters too deep for their preferred 13cm foraging depth

- Wood Storks need specific flood-and-drawdown cycles to concentrate prey—Everglades restoration aims for 1,500–3,000 nesting pairs annually

- Nesting Trends show recovery is underway: South Florida recorded over 52,000 wading bird nests in 2022, more than double the 1999 count

Hydrological impacts remain the biggest challenge. Altered water flow has caused an 80–90% decline in historical nesting numbers. Urban adaptation by ibises demonstrates resilience, yet conservation status varies widely. Management initiatives under the Extensive Everglades Restoration Plan are helping, but water bird identification experts note current populations still fall short of restoration targets set to approximate historic abundances.

Ducks, Geese, and Swans

Beyond Florida’s waders, the state’s lakes and wetlands are transformed by a variety of waterfowl, including ducks, geese, and swans. Among these, four resident duck species call Florida home year-round: the mottled duck, wood duck, and two species of whistling-ducks. Canada geese have also established permanent residency, with their population expanding rapidly at an annual rate of approximately 10%. Of the seven swan species recorded in Florida, only the tundra swan is native; the rest were introduced.

| Group | Resident Species | Conservation Pressures |

|---|---|---|

| Ducks | Mottled, wood, black-bellied & fulvous whistling-ducks | Mottled duck declined 78% since 1966; hybridization with feral mallards threatens genetics |

| Geese | Canada goose (year-round in north/central Florida) | Populations growing 10% yearly; individual birds produce 1,000 lbs of feces annually, affecting water quality |

| Swans | Tundra swan (native); mute swan (introduced, managed) | Mute swans spread fivefold but unlikely to sustain wild populations; captive birds regulated to prevent disease spread |

Waterfowl hunting significantly impacts these populations. Florida hunters lead the nation in ring-necked duck harvest, with approximately 140,000 birds taken recently, and contribute nearly half of the total mottled duck harvest. Conversely, black-bellied whistling-ducks are thriving, with U.S. populations increasing by roughly 8% annually.

Climate change poses a significant threat to these species, particularly through sea-level rise. Projections indicate up to 1 meter of additional rise by 2100, endangering coastal marshes. This is especially concerning for mottled ducks, whose distinct Florida population numbered around 42,000 breeding individuals in the most recent comprehensive survey. Conservation assessments suggest that up to 76% of Florida’s species, including wetland-dependent waterfowl, may face challenges in moving inland as habitats shift.

Resident ducks can be spotted in freshwater wetlands across the state, while wintering species migrate from northern breeding grounds. Canada geese are frequently found on golf courses and parks with mowed grass near ponds, particularly in Leon and Duval counties. Mute swans often inhabit city parks and managed lakes, where populations, such as the 84 individuals at Lake Morton, require active management to prevent overgrowth.

Rails, Coots, and Gallinules

Marshes and wetlands across Florida hide some of the state’s most secretive residents: rails, coots, and gallinules. You’ll find at least five species regularly, including the American coot and purple gallinule, each adapted to life among dense vegetation.

These marshbirds face real challenges:

- Purple gallinules show long-term declines since 1966

- Clapper rails rely on 170,000 hectares of threatened salt marsh

- Wetland losses historically reached hundreds of thousands of acres yearly

Understanding wetland ecology helps you spot these elusive birds during marshbird migration.

Water Bird Habitats Across Florida

Florida’s water birds don’t all hang out in the same places. Some prefer the quiet calm of marshes and wetlands, while others feel right at home on busy coastal beaches or peaceful lakes.

Let’s look at the different habitats where you can spot these birds across the state.

Wetlands and Marshes

You’ll find Florida’s wetland habitats—including marshes, swamps, and wet prairies—are where water birds truly thrive. These areas support herons, egrets, and wood storks by offering rich foraging grounds shaped by hydrological patterns and seasonal flooding.

Wetland bird trends show promising increases in nesting, thanks to habitat management and restoration efforts. Yet conservation challenges like development and invasive species still threaten marsh ecology across the state.

Coastal Beaches and Estuaries

Along Florida’s coast, you’ll spot pelicans, terns, and shorebirds thriving on sandy coastal areas and in estuaries. These coastal habitats are essential for nesting success and foraging, though environmental stressors like erosion and habitat degradation pose real challenges.

Population monitoring shows some species rebounding while others decline. Restoration initiatives focusing on living shorelines help protect seabirds from rising tides and storms that threaten their future.

Lakes, Rivers, and Freshwater Ponds

Florida’s freshwater lakes, rivers, and ponds host impressive water bird species richness—often 16 species per site—thanks to hydrology influence and nutrient cycling that shape habitat quality.

You’ll find abundance density varies widely, from 7 to 800 birds per square kilometer, depending on aquatic vegetation and rainfall patterns.

Habitat management efforts, including wetland restoration, help sustain these diverse wetland habitats for wading birds, ducks, and diving species throughout the state.

Key Birdwatching Locations

You’ll discover outstanding Florida birdwatching along the Great Florida Birding Trail‘s 2,000 miles and nearly 500 sites. Trail accessibility varies by location, with elevated boardwalks at Wakodahatchee Wetlands and observation towers near Apalachicola River.

Seasonal variations bring different species—winter waterfowl in Panhandle wetlands, nesting wood storks at Corkscrew Swamp.

Refuge programs at J.N. “Ding” Darling support conservation while ecotourism impact funds habitat protection across coastal areas.

Unique Adaptations of Florida Water Birds

Florida’s water birds have evolved some pretty impressive tools and tricks to survive in their watery worlds. From specialized bills that work like fishing gear to flight patterns that save energy, each species has its own set of adaptations.

Let’s look at the key features that help these birds thrive in Florida’s diverse aquatic habitats.

Feeding Strategies and Bills

When you’re watching water birds in Florida, their bills tell the whole story of how they catch dinner. Bill shape drives everything from prey detection to diet composition. Here’s how different feeding behavior works:

- Herons use pointed bills for lightning-fast strikes, with fish making up over 55% of what they eat

- Brown pelicans plunge-dive from 20 feet up, their pouches holding 3 gallons of water

- Spoonbills sweep side-to-side in muddy shallows, detecting prey by touch alone

- White pelicans practice cooperative foraging, herding fish into tight groups

These water bird feeding habits show how habitat influence shapes foraging strategies of birds across Florida’s diverse wetlands.

Plumage and Camouflage

Beyond bills, water bird plumage characteristics tell you where each species hunts. You’ll notice cryptic coloration in Least Bitterns hiding among cattails, while countershading patterns in Great Blue Herons reduce shadows at the water’s edge.

Seasonal molting shifts ducks into duller eclipse plumage after breeding. Age-related plumage changes make juvenile Little Blue Herons white before turning blue-gray.

Even glossy plumage in ibises reflects surrounding vegetation colors.

Wingspans and Flight Patterns

Water bird wingspan and flight styles let you identify species from a distance. Great Blue Herons reach wingspans up to 79 inches and fly with necks tucked. Brown Pelicans glide just above waves at 14–35 mph, conserving energy through soaring vs. flapping.

Watch for formation flying in ibises and ducks along migration routes—V-shaped patterns cut energy costs by drafting behind neighbors.

Nesting Behaviors

Once you’ve spotted a bird in flight, you’ll want to know where it goes to breed. Many Florida waders nest in large colonies rather than alone. Great egrets and great blue herons claim the tallest trees, while smaller herons tuck nests below the canopy.

Colony structure matters—islands offer protection from predators, and nesting effort peaks when water levels drop steadily through winter.

Identification Tips for Florida Water Birds

Spotting water birds in Florida gets easier once you know what to look for. Each species has its own set of clues—from bill shape and size to the way they move and sound. Let’s walk through the key features that’ll help you identify these birds in the field.

Distinguishing Features by Species

When you’re trying to nail bird identification in Florida, focus on a few key physical characteristics that’ll separate one species from another.

Start with plumage variations—Great Egrets wear all white with black legs, while Snowy Egrets flash those bright yellow feet. Bill morphology matters too. Roseate Spoonbills sport that unmistakable flat, spatula-shaped bill, whereas Wood Storks carry heavy, slightly down-curved ones.

Size comparison helps in habitat overlap zones where multiple species gather.

Seasonal Plumage Changes

Throughout the year, you’ll notice Florida water birds shift their looks as breeding season comes and goes. Breeding plumage adds ornamental flair that helps with mate selection, while eclipse plumage in ducks keeps males camouflaged during vulnerable molt cycles. Diet influence plays a role too—carotenoid-rich foods deepen red and pink tones. These seasonal changes affect water bird identification, so watch for:

- Great Egrets developing long back plumes in breeding plumage

- American White Pelicans showing bright orange bills and upper-bill plates

- Blue-winged Teal males in dull eclipse plumage during fall migration

- Double-crested Cormorants sporting head crests and brighter facial skin

- Hybrid plumage in Scarlet-White Ibis crosses shifting from gray-brown to red over two years

Molt cycles coordinate with nesting peaks, so water bird physical characteristics change predictably. Knowing when these shifts happen improves your water bird appearance assessment in the field.

Bird Calls and Vocalizations

Listening to bird calls can sharpen your species recognition skills in Florida’s marshes and beaches. Herons and egrets hear best between 1,000 and 3,000 Hz—the same range where most water bird sounds peak. Rails, coots, and gallinules emit screams, trills, and whistles, while ducks generally vocalize in that 1–3 kHz sweet spot. Black Rails favor nocturnal calls, complicating daytime surveys but offering a unique auditory sensitivity challenge for serious birders.

| Species Group | Call Frequency Range | Peak Activity Time |

|---|---|---|

| Herons & Egrets | 1,000–3,000 Hz | Dawn/Dusk |

| Ducks & Geese | 500–3,000 Hz | Variable |

| Rails & Coots | 500–18,900 Hz | Dusk/Night |

| Cormorants | 1,000–3,000 Hz | Daytime |

| Wood Storks | 1,000–3,000 Hz | Daytime |

Recommended Field Guides and Apps

You’ll appreciate the sharp Guide illustrations in The Sibley Guide and Peterson Field Guide to Birds—both expert resources favored by serious birdwatchers. Beginner guides like Kaufman’s photo-based format simplify avian identification for newcomers.

Digital updates keep the Merlin Bird ID app fresh, with App accuracy reaching 94% for water bird families. Pair a printed bird identification guide with eBird for logging your Florida sightings.

Conservation of Florida’s Water Birds

Florida’s water birds face real challenges, from shrinking wetlands to shifting climates. Some species are hanging on by a thread, while others have made surprising comebacks thanks to focused conservation work.

Let’s look at what’s threatening these birds, what’s being done to help them, and how you can play a part in their future.

Threatened and Endangered Species

Florida’s conservation status listings tell a sobering story. 15 native waterbird taxa are labeled as federally listed, state-designated threatened, or species of special concern, including the wood stork, little blue heron, tricolored heron, and roseate spoonbill. Habitat loss and climate impacts drive these listings, though some species show population recovery.

Conservation efforts, guided by listing criteria, now target six imperiled wading birds through coordinated water bird conservation and bird conservation efforts.

Major Conservation Challenges

You might think habitat loss is yesterday’s problem, but it’s still the number one threat facing Florida’s water birds. Conservation efforts target multiple challenges:

- Habitat degradation from coastal development and altered hydrology

- Climate impacts including sea-level rise and intensified storms

- Water quality degradation from harmful algal blooms

- Population declines in shorebirds and small herons

- Data gaps on migratory waterbird habitat use

These pressures compound each other, making water bird conservation increasingly complex.

Restoration and Management Efforts

Big wins are happening right now across Florida’s wetlands. The Extensive Everglades Restoration Plan is sending more water south, and it’s working—wading bird nests in the Everglades jumped from about 6,800 to nearly 30,000 in one year. Here’s how scientists track progress:

Everglades restoration is working—wading bird nests surged from 6,800 to nearly 30,000 in a single year as scientists track the progress

| Strategy | Focus Area | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrologic Restoration | Water flow timing | Nest numbers quadrupled |

| Species Monitoring | Population trends | Adaptive Management decisions |

| Conservation Planning | Habitat priorities | Targeted protection efforts |

You’re witnessing ecosystems healing in real time.

How Birdwatchers Can Help

You can make a real difference once those restoration efforts take hold. Here’s how birdwatchers and birders support wetland bird conservation:

- Data collection – Submit your sightings to citizen science programs like eBird; Florida’s one of the top three states for participation.

- Habitat monitoring – Join water-quality checks or track nest disturbance at key sites.

- Public education – Lead cleanups and teach others about responsible birdwatching near nesting zones.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What kind of birds go underwater in Florida?

You might think all water birds stay above the surface, but diving birds like Anhingas, cormorants, and diving ducks completely submerge to hunt.

They use unique buoyancy adaptations and underwater foraging techniques throughout Florida’s waters.

What is the underwater bird in Florida?

You’ll recognize the Anhinga as Florida’s signature underwater forager—it swims submerged with just its snakelike neck visible, spears fish with a dagger bill, then spreads wings to dry its water-soaked feathers.

What is the big grey water bird in Florida?

You’ll spot Florida’s tallest wading heron—the Great Blue Heron—standing like a statue in shallow water.

It reaches four feet tall with a six-foot wingspan, making it unmistakable among Florida’s water birds.

What is the common water bird?

You’ll find several common water bird species across North America, but in Florida, white ibis leads in abundance ranking through population monitoring and citizen science data, followed closely by great egret in wetland bird habitats statewide.

What kind of bird swims underwater in Florida?

You’ll often catch two standout diving specialists in Florida: the anhinga and the double-crested cormorant. Both plunge underwater after fish, using unique adaptations and foraging strategies for efficient aquatic hunting.

What is the loud Florida water bird?

The Limpkin’s haunting screams make it Florida’s loudest water bird. You’ll hear their piercing wails echoing through wetlands, especially at night during breeding season—a sound that’s hard to forget once you’ve experienced it.

What is the large white water bird in Florida?

The great egret is Florida’s most common large white water bird, though American white pelicans, wood storks, and white ibises also appear frequently.

Seasonal variations help distinguish herons, egrets, and bitterns from pelicans across wetlands.

What is the GREY wading bird in Florida?

When you spot a tall grey wading bird standing statue-still in shallow Florida water, you’re almost certainly looking at a Great Blue Heron—our largest common grey Heron vs Crane frequently confused with cranes due to similar size.

What is the diet of Floridas water birds?

Florida’s water birds display diverse feeding habits shaped by prey availability and seasonal variations. Fish dominate heron and egret diets, while ibises prefer crustaceans.

Dietary overlap influences feeding techniques, and these patterns directly affect water bird diet and reproduction success.

How do Florida water birds adapt to climate change?

You’ll notice migration timing shifting earlier in spring and later in fall as temperatures warm.

Many species are moving their breeding ranges northward, while coastal birds relocate inland when sea levels rise and alter foraging zones.

Conclusion

It’s ironic that Florida’s water birds—survivors of hurricanes, droughts, and prehistoric extinctions—now face their biggest threat from us. Yet you hold real power here.

Every identification you make sharpens your awareness. Every habitat you protect creates refuge. Every sighting you report helps scientists track populations. Learning about water birds in Florida isn’t just birdwatching—it’s joining a network of people who’ve decided these ancient survivors deserve a fighting chance in the modern world.

- https://www.wgcu.org/section/environment/2025-03-12/wading-bird-nesting-underway-in-south-florida-how-is-the-comparison-to-recent-years

- https://www.sfwmd.gov/sites/default/files/documents/SFWBR_2020_Final.pdf

- https://wec.ifas.ufl.edu/about-wec/research/wading-bird/findings/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10402381.2025.2515589?src=exp-la

- https://www.audubon.org/florida/news/state-birds-report-highlights-need-focused-research-and-fast-action