This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

You’ll find these compact divers bobbing on wooded wetlands throughout North America, disappearing beneath the surface with barely a ripple as they hunt for submerged plants and invertebrates.

Despite the confusion over its name, this adaptable species has carved out a successful niche in both wild marshes and suburban retention ponds.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What is a Ring-Necked Duck?

- How to Identify Ring-Necked Ducks

- Where Do Ring-Necked Ducks Live?

- What Do Ring-Necked Ducks Eat?

- Conservation Status and Key Threats

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Are ring neck ducks rare?

- What is another name for Ring-necked Duck?

- What kind of duck has a ring around its neck?

- What is the difference between Ring-necked Duck and tufted duck?

- What is the average lifespan of a Ring-Necked Duck?

- How do Ring-Necked Ducks protect themselves from predators?

- Can Ring-Necked Ducks be found in urban environments?

- What is the purpose of the Ring-Necked Ducks distinctive call?

- Are Ring-Necked Ducks considered an endangered species?

- How do Ring-Necked Ducks communicate with each other?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- The ring-necked duck’s name misleads birders because the faint chestnut neck collar is nearly impossible to spot in the field, while the bold white bill ring serves as the most reliable identification marker.

- These adaptable diving ducks thrive across diverse habitats from remote boreal wetlands to urban park ponds, with stable populations of 700,000 individuals showing a 1.9% annual increase since 1966 despite ongoing habitat loss.

- Ring-necked ducks shift their diet seasonally, consuming mainly aquatic plants year-round but pivoting to protein-rich insects and mollusks during breeding season while diving to shallow depths of just a few feet.

- Though currently listed as "Least Concern," the species faces real threats from wetland drainage (670,000 acres lost recently), legacy lead poisoning from ammunition, and climate models predicting dramatic northward range shifts out of the lower 48 states.

What is a Ring-Necked Duck?

The Ring-necked Duck is a compact diving species that often puzzles birdwatchers with its misleading name.

You’ll find this duck swimming alongside other waterfowl on lakes and ponds across North America, where its distinctive silhouette and bill pattern stand out more than the neck ring it’s named for.

Understanding its scientific classification, physical traits, and the story behind its confusing name helps you identify this species in the field.

Scientific Classification and Taxonomy

You’ll find the ring-necked duck classified within Animalia, Chordata, Aves, Anseriformes, and Anatidae—a taxonomic hierarchy that places this species squarely among waterfowl. Known scientifically as Aythya collaris, it was first described by Donovan in 1809. Phylogenetic analysis reveals close ties to scaup and tufted ducks, with genetic variation studies showing moderate differentiation across North American Aythya species.

The species nomenclature references that elusive chestnut collar—though ornithology jokes it’s the bill ring you’ll actually spot in the field. Further research on diving duck habits can provide valuable insights into the behavior and characteristics of the Ring-necked Duck.

Overview of Physical Appearance

Beyond taxonomy, you’ll notice this compact diving duck shows a head shape that shifts with every dive—sloping forehead and peaked crown flattening as it disappears underwater.

Aythya collaris measures 14–18 inches—crow-sized—with feather patterns that split sharply by sex. Males flash glossy black heads and backs against white flanks; females wear grayish-brown plumage with subtle pale patches.

Both sport distinctive beak color rings that outshine the species’ namesake collar, making Ringnecked Duck field identification surprisingly straightforward once you know where to look.

Unique Name Origin and Misconceptions

You’d think a duck named for its neck ring would sport that feature proudly, but the brownish collar on Aythya collaris is so subtle that even seasoned birders rarely catch it in the field.

The name traces back to specimen collectors who worked from dead birds in hand—not from watching them alive. This naming quirk still shows up in Audubon Field Guides, even though:

- The collar requiring perfect light and close range

- Bill rings being far more visible for bird species identification

- Ornithological research suggesting "Ring-billed Duck" would’ve nailed the Duck Misconceptions

Species Naming often immortalizes features you’ll never actually see—that’s the Ringnecked Duck’s ironic legacy.

How to Identify Ring-Necked Ducks

Spotting a Ring-necked Duck in the field isn’t always straightforward—especially when that famous neck ring rarely shows itself.

You’ll need to look beyond the misleading name and focus on bill patterns, head shape, and plumage contrasts that actually stand out.

Here’s what separates this compact diver from the crowd.

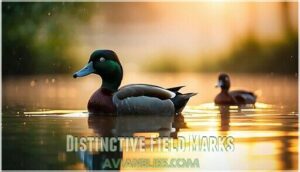

Distinctive Field Marks

If you’re scanning a flock of ducks on open water, you’ll want to lock onto the Ring-necked Duck’s most reliable field mark: a bold white ring encircling the bill near the tip, creating a sharp contrast that stands out even at a distance. Beyond beak color, look for the peaked head shape—almost triangular when alert—and check for eye rings in females, which form pale orbital crescents.

When you’re sorting through a raft of ducks, keep an eye out for these key differences:

| Field Mark | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Head Shape | Angular, peaked crown | Rounded, sloping forehead |

| Eye Rings | Faint or absent | White, conspicuous |

| Neck Bands | Chestnut (rarely visible) | Pale collar at bill base |

Once you recognize these field marks and plumage details, identifying ring-necked ducks becomes second nature.

Male Vs. Female Differences

Sexual dimorphism hits hard in this species—males and females wear plumage so different you’d swear they belong to separate flocks. Males flash glossy black heads and chests with white flanks—a striking contrast for mating rituals. Females stay cryptic in gray-brown tones with pale face patches, aiding sex determination in the field.

What sets duck species apart:

- Head colors: Males show iridescent purple-black; females display muted browns

- Beak shapes: Both sexes carry white bill rings, but males sport brighter patterns

- Plumage variations: Males contrast sharply; females blend into marshland cover

You’ll find this same pattern in waterfowl and songbirds worldwide.

Comparison With Redhead and Scaup

Misidentifying diving ducks happens fast when redhead, scaup, and ring-necked species mix on open water. Redheads show cinnamon-red heads and gray backs, while scaup flash white wing stripes and broader beaks. Ring-necked ducks stand apart with peaked heads, black backs in males, and distinctive white side spurs.

During duck migration, habitat overlap creates mixed flocks—redheads favor deep vegetation zones, scaup cruise larger lakes, and ring-necked ducks stick to smaller ponds. Flocking behavior and feather patterns reveal identity: scaup fly in tight, synchronized groups showing bold white secondaries, while ring-necked waterfowl travel in looser formations with subtler wing markings. Understanding the waterfowl habitats is essential for identifying these species accurately.

Where Do Ring-Necked Ducks Live?

Ring-necked Ducks don’t just stick to one type of water—they’re found across a surprising range of habitats depending on the season. From remote boreal wetlands to city park ponds, these adaptable divers shift their territory as the year unfolds.

Let’s trace their movements through the seasons.

Breeding Range and Preferred Summer Habitats

You’ll find Ring-necked Ducks breeding across Canada’s boreal forests and into Alaska, pushing south through Minnesota and Michigan. During the breeding season, these waterfowl favor freshwater marshes, bogs, and small wooded ponds—especially shallow sites under four feet deep with dense sedges and emergent vegetation.

They’re choosy about nesting sites, building directly over water on floating mats. Habitat selection centers on beaver ponds and acidic wetlands where breeding patterns thrive, with typical densities reaching 4.3 to 16.7 pairs per 100 acres in quality wildlife habitat.

Winter Migration Routes and Destinations

When autumn arrives, Ring-necked Ducks abandon their northern breeding grounds and funnel southward along well-worn flyways, with most birds traveling through the Mississippi and Atlantic corridors to reach wintering sites stretching from the southern United States deep into Central Mexico.

Migration timing peaks in October and November, with stopover sites along rivers and large lakes providing critical refueling habitat.

Once on their wintering grounds, you’ll spot these waterfowl on freshwater lakes, coastal estuaries, and flooded marshes where conservation efforts protect essential foraging areas.

Urban and Suburban Habitat Use

You don’t need to venture far into wilderness to encounter Ring-necked Ducks—these adaptable divers have quietly made themselves at home in city parks, suburban retention ponds, and even golf course water hazards where manicured landscapes meet their need for open water and aquatic vegetation.

When cities preserve these suburban wetlands, they’re not just protecting waterbird habitat—they’re creating living corridors where avian life can flourish. Look where these ducks show up:

- City ponds with managed aquatic plants

- Backyard habitats connected to larger wetland corridors

- Industrial park detention basins offering unexpected wildlife biology refuges

Protecting these wetland spaces helps duck populations stay strong and adaptable.

What Do Ring-Necked Ducks Eat?

Ring-necked Ducks aren’t picky eaters—they’ll grab whatever’s available beneath the surface. Their menu shifts with the seasons and where they’re swimming, mixing plants with small critters depending on what’s easiest to reach.

So what do they actually eat?

Typical Diet by Season

Ring-necked Ducks shift their menu with the seasons, leaning heavily on aquatic plants during most of the year but pivoting to protein-rich insects and mollusks when breeding demands extra energy.

During winter feeding periods, you’ll find them targeting nutrient sources like hydrilla and waterlily seeds across varied waterbird habitats.

These diving ducks showcase notable dietary adaptations, with studies revealing seasonal foraging patterns tied to duck migration patterns and regional availability—essential knowledge for understanding avian biology across bird species.

Foraging Behaviors and Techniques

Watch these compact divers in action, and you’ll see why their feeding strategy sets them apart from dabbling ducks that tip and paddle at the surface. Ring-necked Ducks employ distinct diving techniques to access aquatic food sources:

- Dive depths of just a few feet – shallow enough to reach submerged vegetation without wasting energy

- Direct vertical plunges – they vanish underwater in seconds, unlike surface-skimming bird species

- Opportunistic surface grazing – they’ll up-end in shallows when easy meals present themselves

- Explosive takeoffs – their powerful flight lets them relocate quickly between foraging strategies across varied wildlife habitat conservation areas

Role in Aquatic Ecosystems

Beyond their impressive feeding repertoire, these diving ducks play an understated but meaningful part in the wetlands they inhabit year-round. Their aquatic predation controls invertebrate populations, while their constant movement through vegetation fosters water quality and ecosystem engineering.

Diving ducks play several key roles in biodiversity conservation:

| Ecological Role | Mechanism | Conservation Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Seed dispersal | Transport plant material between wetlands | Supports habitat restoration efforts |

| Nutrient cycling | Redistribute nutrients via excretion | Enhances environmental conservation efforts |

| Vegetation control | Consume excessive aquatic plant growth | Maintains balanced wildlife habitat conservation |

| Food web linkage | Connect benthic zones to surface predators | Strengthens avian behavior and ecology networks |

Where you find these ducks thriving, you’re likely looking at a wetland ecosystem in good health—one that deserves attention and protection.

Conservation Status and Key Threats

Ring-necked Ducks aren’t in trouble, but they face real challenges you should know about. The species holds steady globally, yet habitat loss and lingering contamination threaten local populations.

Below, you’ll find what experts are watching—and the steps being taken to protect these diving ducks.

Current Population Trends

Remarkably, Ring-necked Ducks have bucked the decline narrative. Their 2024 breeding population sits at 700,000 individuals—stable against long-term averages. Since 1966, numbers climbed 1.9% annually, defying habitat loss across boreal forests. Here’s what shapes their population dynamics:

- Breeding success hinges on May pond counts in Canadian wetlands

- Migration patterns concentrate hundreds of thousands on single Minnesota lakes each fall

- Conservation efforts under the North American Wetlands Conservation Act lifted all waterfowl 24% since 1970

- IUCN status remains "Least Concern," reflecting adaptability in diving ducks

- Annual harvest averages 392,555 birds, yet populations hold firm

These gains didn’t just happen—they’re the result of decades of coordinated conservation work.

Major Conservation Concerns

Despite stable numbers, threats loom. Wetland loss jumped 50% recently—670,000 acres gone, draining breeding grounds. Lead poisoning persists from legacy ammunition littering wetland bottoms where you’ll find these divers feeding.

Climate change models predict their range will shift dramatically northward, evacuating the lower 48 states. Pollution effects and wetland degradation erode food sources, while habitat preservation strategies struggle in remote boreal forests.

Wildlife conservation efforts face an uphill battle against agricultural drainage and acidification—challenges that demand your attention if we’re protecting this IUCN-listed species long-term.

Ongoing Protection and Management Efforts

Federal action confronts threats head-on. The 1991 lead shot ban cut poisoning deaths, while the Migratory Bird Treaty Act guards Ring-necked Ducks nationwide.

Habitat restoration anchors efforts—boreal wetlands preserved, refuges expanded. Wildlife conservation programs track 800,000 birds annually through satellite telemetry and banding, fine-tuning harvest limits.

Ecosystem management partnerships restore flooded fields and nesting zones. Species protection hinges on adaptive management: Bird Species Identification drives surveys, Ornithological Research maps wildlife migration patterns, and Biodiversity Preservation secures their future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are ring neck ducks rare?

No—this diving duck isn’t rare at all. Population trends show over 700,000 individuals in North America, earning them Least Concern status.

You’ll find these adaptable ducks thriving across wetlands, though habitat loss remains a conservation concern worth monitoring.

What is another name for Ring-necked Duck?

Ever wondered if birders use shortcuts when calling out ducks? You’ll hear some waterfowl enthusiasts call this diving duck a "ringneck"—a practical abbreviation that’s caught on among hunters and field observers.

Others lump it with similar species like Lesser Scaup under the broader term "scaup," though that’s technically imprecise for bird nomenclature and waterfowl names.

What kind of duck has a ring around its neck?

You won’t find many ducks sporting visible neck rings. The Ring-necked Duck’s name is misleading—its chestnut collar is nearly impossible to spot.

Instead, look for bold bill rings that actually stand out in the field.

What is the difference between Ring-necked Duck and tufted duck?

You’ll spot the difference in their bills and heads right away. Ring-necked Ducks sport peaked crowns and white bill rings, while Tufted Ducks show off drooping head crests and plain dark bills—both dive deep in overlapping boreal forest wetlands.

What is the average lifespan of a Ring-Necked Duck?

You’ll find that Ring-necked Ducks generally live 2-3 years in the wild, though some individuals push past a decade when conditions align.

Avian lifespan depends heavily on predation, habitat quality, and hunting pressure—wildlife survival isn’t guaranteed.

Like Mallards and other North American waterfowl, duck longevity reflects the harsh realities of bird mortality and species durability across diverse migration habits.

How do Ring-Necked Ducks protect themselves from predators?

You’d think a duck dressed in bold black-and-white would have nowhere to hide—yet ring-necked ducks vanish like smoke when danger strikes. They rely on diving escapes, plunging beneath the surface in seconds to evade aerial predators.

Flock behavior and vigilance techniques keep watch while feeding, and their camouflage strategies blend perfectly with boreal forest wetlands and Prairie Pothole Region marshes where mallard and other bird species also find refuge.

Can Ring-Necked Ducks be found in urban environments?

You’ll spot these diving ducks in urban parks and city wetlands more than you’d think. They adapt surprisingly well to park ponds and backyard feeders, moving between boreal forest breeding grounds and developed areas—a classic example of urban wildlife adaptation.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology documents this phenomenon in their bird species overview on avian biology.

What is the purpose of the Ring-Necked Ducks distinctive call?

You won’t find much documentation on Ring-necked Duck vocalizations—they’re relatively quiet compared to other waterfowl. Males produce soft whistles during courtship displays, while females give low grunts.

These calls primarily function as mating signals and aid social bonding within flocks. Vocal learning in ducks remains less studied than in songbirds, according to Cornell Lab of Ornithology research on duck communication and avian biology.

Are Ring-Necked Ducks considered an endangered species?

No, Ring-necked Ducks aren’t remotely close to endangered—they’re thriving with stable populations.

Conservation efforts focus on protecting breeding habitats like cattail marshes and beaver ponds across the Prairie Pothole Region, addressing habitat loss and lead poisoning risks.

How do Ring-Necked Ducks communicate with each other?

You’ll hear vocal calls and see visual displays during courtship—males emit soft whistles and cooing sounds while performing head-throws. Females respond with hoarse quacking patterns.

In prairie pothole region beaver ponds and cattail marshes, these social interactions intensify during migration, with feather signals like crest-raising communicating alarm or aggression.

Conclusion

Like a phantom moving through still waters, the ring-necked duck reminds us that names don’t always reveal the full story. You’ve learned to look past the misleading moniker and spot the real field marks—that striking white bill ring, compact silhouette, and diving prowess.

The ring-necked duck’s misleading name hides its true field mark—a bold white bill ring that outshines the collar you’ll never see

From city ponds to wild marshes, spotting these adaptable ducks does more than pad your life list—it’s a window into how our wetlands are doing.

Keep an eye out for them. Support the spaces they need. That’s how we keep these skilled divers around for the long haul.

- https://ace-eco.org/vol17/iss2/art5/

- https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2025-09/waterfowl-population-status-report-2025.pdf

- https://www.ducks.org/hunting/waterfowl-id/ring-necked-duck

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ring-necked_Duck/lifehistory

- https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Aythya_collaris/