This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

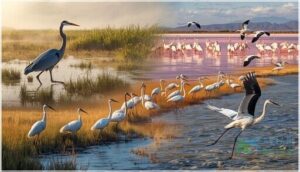

A flamingo’s legs can bend backward—or so it seems when you watch one standing knee-deep in a salt lake. That visible joint isn’t a knee at all; it’s an ankle, and the real knee hides beneath feathers near the body. This anatomical sleight-of-hand reveals why birds with long legs dominate wetlands, grasslands, and shorelines across every continent except Antarctica.

Extended limbs aren’t just for show—they let herons spear fish in deeper channels, let cranes spot predators over tall grasses, and let stilts wade through shallows without soaking their plumage. Each species tailors leg length to its niche, turning bone and tendon into tools for survival, courtship, and migration.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What Makes Birds Have Long Legs?

- Notable Long-Legged Bird Families

- Iconic Species With Long Legs

- Habitats and Global Distribution

- Conservation Challenges and Efforts

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Why do birds have long legs?

- Do egrets have long legs?

- Are there any birds with long legs in North America?

- What is a bird with long legs?

- Are hummingbirds long legs?

- What kind of bird has long legs?

- What is a grey bird with long skinny legs?

- What kind of bird has long legs in the pond?

- What are the black and white birds with long legs?

- What bird is known for its long legs?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Long legs evolved as survival tools that let birds wade deeper, run faster, and regulate body heat while dominating wetlands, grasslands, and shorelines across continents.

- The visible “backward knee” on flamingos and herons is actually an ankle—the true knee hides beneath feathers near the body, revealing how bone structure shapes each species’ ecological niche.

- Extended limbs deliver multiple evolutionary advantages including faster predator escape, enhanced courtship displays, energy-efficient locomotion, and access to feeding zones other birds can’t reach.

- Conservation threats like habitat destruction, water pollution, and climate shifts have pushed species such as Whooping Cranes and Siberian Cranes toward extinction, making wetland protection critical for their survival.

What Makes Birds Have Long Legs?

Long legs didn’t just happen by accident—they’re the result of millions of years of adaptation to specific environments and survival needs. Birds evolved these striking limbs to wade through water, outrun predators, and even catch the attention of potential mates.

Long legs evolved over millions of years to help birds wade through water, escape predators, and attract mates

Let’s look at the key reasons behind this extraordinary feature.

Evolutionary Advantages of Long Legs

Survival rewards innovation, and long legs deliver multiple payoffs. You’ll find wading birds accessing deeper feeding zones without soaking their feathers, conserving energy as their extended limbs reduce sinking in soft substrates.

Leg length benefits include faster locomotion speed for predator avoidance and pursuit, plus enhanced visibility during courtship displays.

These evolutionary traits reflect millions of years of natural selection refining avian anatomy and physiology across diverse habitats. The study of these adaptations requires careful consideration of scientific writing guides.

Physical Adaptations for Wading and Running

Long legs aren’t just about height—they’re biomechanical marvels. You’ll notice wading birds sporting elongated tarsometatarsus bones that slash submergence depth while you watch them hunt in shallow water. Bird anatomy reveals three game-changing adaptations:

- Leg bone structure extends stride length for both sprint and stalk

- Tendon elasticity stores energy during each step, boosting muscle efficiency

- Foot morphology spreads weight across soft mud, preventing you from witnessing a graceless sink

These features make leg length a survival asset across wetlands and grasslands. Balance mechanisms coordinate precise foot placement through proprioceptive feedback, while layered muscle architecture underpins both patient foraging and explosive takeoff. Avian anatomy and physiology transform simple limbs into multipurpose tools.

Understanding the importance of scientific writing is essential for effectively communicating research findings on bird adaptations.

Role in Balance, Display, and Mating

Beyond locomotion, those towering limbs orchestrate balance techniques on marshy ground—you’ll see herons freeze mid-stride, tendon adjustments keeping their center of gravity rock-steady.

Leg posture amplifies courtship signals: cranes march with exaggerated steps, translating leg length into mating strategies that broadcast vigor.

Display rituals coordinate wing sweeps with foot choreography, turning bird adaptation into visual theater. Mating and breeding success hinges on these leg-driven performances, where bird behavior meets evolutionary showmanship in mating rituals.

Notable Long-Legged Bird Families

Long-legged birds belong to several distinct families, each adapted to specific environments and lifestyles. You’ll find these birds across wetlands, grasslands, and coastal zones worldwide.

Let’s explore the key families that showcase nature’s most impressive leg adaptations.

Herons, Egrets, and Bitterns

Herons, egrets, and bitterns form a diverse clade of wading birds built for shallow-water foraging. Their leg structure features long, thin toes that let you spot them balancing on mud or vegetation in wetlands.

These bird species characteristics include specialized hunting strategies—some stand motionless, while others stalk prey with patience. Feather camouflage and deliberate wading techniques make them expert wetland hunters with distinct nesting habits.

Cranes and Storks

Cranes and storks stand tall among wading birds, with long legs that lack webbing between widely spaced toes. Their courtship displays blend aerial acrobatics with ground movements, showcasing leg anatomy built for both terrestrial locomotion and shallow-water foraging.

Cranes’ migration patterns span continents, while stork behavior includes distinctive red-colored legs and wading techniques that let these bird species characteristics shine in wetlands worldwide.

Flamingos and Spoonbills

You’ll spot flamingos and spoonbills by their unique feeding habits—flamingos filter-feed on microscopic prey with specialized bills, while spoonbills use clawed toes to grip mud. Their leg structure enables wading in wetlands where aquatic birds thrive.

Habitat preferences lean toward tropical marshes and coastal zones, and mating rituals often feature synchronized displays that highlight their social behavior among wading birds.

Ostriches and Emus

Flightless birds like ostriches and emus rely on powerful leg anatomy for survival. You’ll see these large-bodied champions sprint at impressive speeds across open terrain, showcasing terrestrial adaptation at its finest.

Their long-legged design delivers:

- Stride length – Each step covers more ground than most bird species

- Muscular power – Thick tendons drive explosive acceleration

- Two-toed grip – Reduced digit count improves traction

- Thermoregulation – Bare legs release excess body heat efficiently

Iconic Species With Long Legs

Some long-legged birds have become icons in their own right, capturing attention through their striking appearance or conservation stories. You’ll recognize these species from documentaries, wildlife photography, or maybe even your own backyard encounters.

Let’s look at five standout examples that showcase the diversity and beauty of long-legged birds around the world.

American Flamingo

You’ll recognize the American flamingo by its striking pink feathers and legs that stretch up to 1.35 meters tall. This wading bird uses its unique leg structure to stand in deep water while filter-feeding on algae and tiny invertebrates. Its diet directly influences feather care and color intensity. During mating rituals, flocking behavior intensifies as birds synchronize displays within their colony.

| Characteristic | Feature | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 1.3–1.5 meters | Deep water access |

| Leg Structure | Elongated tibiotarsus | Wading stability |

| Diet | Algae, invertebrates | Pigment source |

| Social Behavior | Large colonies | Synchronized breeding |

| Plumage | Pink-red coloration | Mate attraction |

Great Blue Heron

You can spot a Great Blue Heron standing motionless in shallow water, reaching 1.1–1.5 meters tall with a wingspan up to 2.0 meters. These long-legged birds excel as wading birds, using patient feeding strategies to spear fish and amphibians.

Their nesting behaviors include colonial rookeries in tall trees. Heron migration patterns vary—some populations stay year-round while others follow seasonal routes across Blue Heron habitat zones.

Whooping Crane

The Whooping Crane stands as a symbol of conservation triumph, reaching about 1.2 meters tall with legs built for marsh navigation and crane migration across vast distances. These endangered wading birds represent what dedicated habitat preservation can achieve.

- Endangered status: Once near extinction with only 15 individuals remaining

- Conservation efforts: Successful breeding programs steadily rebuilding populations

- Nesting behaviors: Longlegged birds construct wetland nests in protected zones

- Bird migration: Travel thousands of kilometers between breeding and wintering grounds

Black-Necked Stilt

The Black-Necked Stilt showcases one of nature’s boldest designs—legs comprising roughly half its body length, giving it unparalleled leg structure among shorebirds.

You’ll find these longlegged birds in wetland habitats across the Americas, where their striking black-and-white plumage and pink legs make them unmistakable.

Their conservation status remains stable, though habitat loss threatens stilt migration routes these wading birds depend on for survival.

Greater Flamingo

The Greater Flamingo stands among the most elegant wading birds, reaching heights of 1.3–1.6 meters with long legs that let you wade into deeper waters than most bird species.

You’ll recognize their striking plumage colors—vivid pink feathers earned through feeding habits focused on algae-rich diets.

Their leg structure facilitates complex social behavior during flamingo migration, when thousands gather in synchronized displays across continents.

Habitats and Global Distribution

Long-legged birds don’t stick to just one type of environment—they’ve adapted to thrive across the globe. You’ll find them wading through wetlands, striding across open grasslands, and migrating thousands of miles with the changing seasons.

Let’s explore the key habitats where these exceptional birds make their home.

Wetlands, Marshes, and Coastal Areas

You’ll find long-legged waterbirds thriving where tidal dynamics shape marsh ecology and aquatic biodiversity flourishes. Wetlands, coastal marshes, and estuaries provide the perfect stage for wading birds and shorebirds to exploit shallow feeding zones.

These habitats face threats from coastal erosion and pollution, making wetland restoration efforts critical. Emergent vegetation creates foraging and nesting substrates, while seasonal water-level shifts drive migratory patterns for these specialized species.

Grasslands and Savannas

Beyond aquatic zones, you’ll spot long-legged waders like cranes and Secretary Birds stalking across savannas where grassland birds hunt vertebrates and invertebrates in open terrain. Ostriches sprint through African grasslands, while cassowaries navigate tropical understory.

These habitats—covering 20–40% of Earth’s land—face habitat fragmentation from agriculture, disrupting wetland dynamics and prey availability. Seasonal rainfall creates temporary pools where savanna ecology and leg adaptations intersect, supporting wildlife ecology across expansive landscapes.

Migration and Seasonal Movements

You’ll witness exceptional avian migration patterns as cranes and flamingos undertake longitudinal shifts spanning thousands of kilometers between breeding and wintering grounds. Seasonal routes follow wetland hydrology cycles and photoperiod cues, with altitudinal movements responding to monsoon floods or droughts.

Bird migration patterns showcase flocking behaviors that conserve energy during these impressive journeys, linking temperate nesting sites to tropical refuges where prey remains abundant year-round.

Conservation Challenges and Efforts

Long-legged birds face mounting pressures that threaten their survival across the globe. Habitat destruction, pollution, and climate shifts have pushed several species to the brink of extinction.

Understanding these challenges—and the efforts to counter them—reveals what’s at stake for these extraordinary waders.

Threats to Wetland Habitats

You’ll notice wetland habitats face mounting pressure from multiple fronts. Habitat destruction through land reclamation strips away essential feeding and breeding sites. Water pollution from agricultural runoff degrades water quality, reducing prey availability. Climate shift intensifies droughts and alters wetland extent. Invasive species disrupt food webs, while altered water management interferes with natural cycles.

Wetland conservation and habitat protection remain essential for maintaining ecological balance.

Endangered Long-Legged Bird Species

You’ll find several endangered species among birds with long legs facing critical conservation status. The Whooping Crane counts roughly 500 individuals in the wild, while the Siberian Crane population remains critically small and fragmented.

Habitat preservation and species research drive recovery plans for these threatened populations. Wildlife conservation efforts focus on threat analysis to protect remaining wetland corridors these long-legged birds depend upon for survival.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why do birds have long legs?

Long legs evolved to help you wade deeper, run faster, and stay cooler. They boost foraging reach and improve balance on soft ground.

These adaptations also enhance locomotion efficiency across wetlands and open terrain.

Do egrets have long legs?

Yes, egrets have long legs relative to their body size. These elongated tarsi allow you to spot them wading in shallow water, foraging with an erect posture that’s characteristic of herons.

Are there any birds with long legs in North America?

You’ll find impressive long-legged species across North America. The Great Blue Heron, Sandhill Crane, Whooping Crane, and Great Egret showcase exceptional leg adaptations for wading techniques through diverse wetland habitats during bird migration.

What is a bird with long legs?

Picture a bird whose elongated legs mirror nature’s adaptive architecture—that’s exactly what defines long-legged species.

These avian forms feature legs proportionally extended for wading, running, or foraging across diverse habitats.

Are hummingbirds long legs?

Hummingbirds have short legs adapted for perching, not wading or running like herons. Their leg structure suits flight patterns and perching behavior, tucking close during flight—ornithologists don’t classify them as long-legged birds.

What kind of bird has long legs?

You’ll spot herons, cranes, storks, flamingos, and ibises wading through wetlands on their striking long legs. These species developed specialized leg structures for moving through shallow water, while ostriches and emus use theirs for sprinting across open terrain.

What is a grey bird with long skinny legs?

You’re likely spotting a Grey Heron. This wading bird shows blue-grey plumage and remarkably slender legs built for stalking fish in shallow wetlands.

Great Egrets and Sandhill Cranes also display similar grey tones and long-legged wading techniques.

What kind of bird has long legs in the pond?

You’ll find herons stalking through pond shallows, their long legs perfectly adapted for wading.

Black-necked stilts and green herons also frequent these wetland habitats, using elongated limbs to probe muddy substrates for prey.

What are the black and white birds with long legs?

You’ll encounter striking contrasts in wetland ecology: the Black-necked Stilt displays vivid pink leg coloration, while Pied Avocets showcase upturned bills.

These wading birds demonstrate exceptional avian adaptations, enabling precise species identification across diverse habitats and supporting bird migration patterns.

What bird is known for its long legs?

The American flamingo stands out for its striking pink legs reaching 35 meters. Ostriches claim the longest legs among all birds, while black-necked stilts showcase remarkably slender proportions for wading through shallow waterways.

Conclusion

Long before GPS tracked migratory paths, birds with long legs navigated coastlines and wetlands through instinct alone. You’ve seen how anatomy dictates survival—stilts probing mud, cranes surveying plains, flamingos filtering brine.

Each species carries millennia of refinement in its femur and tarsus, proof that form follows function across every ecosystem they occupy. Protect the marshes and grasslands they depend on, and you preserve living blueprints of adaptation that predate human civilization by epochs.

- https://www.neonsigns.com/us/custom-neon-signs

- https://www.flyaviary.com/types-of-birds-that-start-with-s/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bird

- https://academichelpexpress.blog/2024/08/please-use-the-bulleted-points-and-the-rubric-below-to-guide-your-work-your-pa/

- https://x.com/godofprompt/status/1990526288063324577