This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

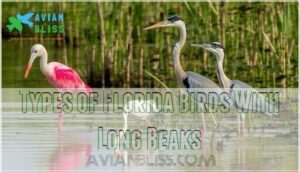

The White Ibis uses its curved bill like a probe to hunt crayfish, while Great Blue Herons spear fish with dagger-sharp precision.

Wood Storks swing their massive bills through murky water like metal detectors, and Roseate Spoonbills sweep side-to-side with their spatula-shaped beaks.

Black-necked Stilts wade on impossibly long legs, picking insects with needle-thin bills.

Each species has evolved its beak shape for specific feeding strategies—curved for probing, straight for spearing, or spatulate for filtering, and timing and location make all the difference when spotting these specialized hunters with their unique beak shapes, such as the curved bill and spatula-shaped beaks.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Types of Florida Birds With Long Beaks

- White Ibis

- Limpkin

- Long-billed Dowitcher

- Long-billed Curlew

- Black-necked Stilt

- Willet

- Whimbrel

- American Oystercatcher

- American Avocet

- Roseate Spoonbill

- Great Egret

- Snowy Egret

- Great Blue Heron

- Little Blue Heron

- Tricolored Heron

- Wood Stork

- Whooping Crane

- American White Pelican

- Brown Pelican

- Black Skimmer

- Ruby-throated Hummingbird

- Bird Identification Tools

- Birding Locations in Florida

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- You’ll discover over 25 species of long-beaked birds thriving in Florida’s wetlands, each with specialized beak shapes—curved for probing like the White Ibis, straight for spearing like herons, or spatula-shaped for filtering like Roseate Spoonbills.

- You can spot these birds year-round in diverse habitats from coastal beaches where American Oystercatchers crack shells to freshwater marshes where Wood Storks use tactile feeding, making Florida a premier destination for birding enthusiasts.

- You’ll need proper identification tools like quality binoculars and birding apps since subtle differences in beak shape, size, and feeding behavior distinguish similar species—understanding these features helps you appreciate each bird’s evolutionary specialization.

- You should time your birding trips for early morning (5:30-9:00 AM) or late afternoon (4:00-6:30 PM) during peak feeding periods, with spring migration (April-May) offering the highest species diversity and winter months concentrating birds in warmer habitats.

Types of Florida Birds With Long Beaks

Florida’s wetlands and coastlines serve as a living showcase for over 25 long beak birds, each displaying remarkable adaptations that’ll make you appreciate nature’s engineering.

These florida bird species have evolved diverse bird beak shapes perfectly suited for their unique feeding habits. From the spoon-tipped roseate spoonbill to the needle-sharp black-necked stilt, each long billed birds species tells a story of survival and specialization.

Nature’s architect designed each beak as a specialized tool, perfectly crafted for survival in Florida’s diverse wetlands.

Wading birds florida residents like herons and ibises use their extended beaks as precision tools for nabbing fish, frogs, and crustaceans.

Bird migration patterns bring additional species seasonally, creating incredible habitat diversity opportunities. Understanding beak functions helps you identify these magnificent creatures while appreciating their conservation status and ecological importance in Florida’s diverse ecosystems.

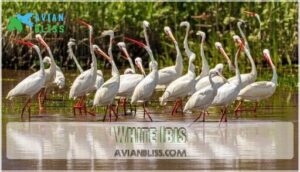

White Ibis

With that elegant curved bill sweeping through shallow waters, you’ll instantly recognize the White Ibis as one of Florida’s most iconic wading birds florida.

These long beak birds use their specialized beaks for tactile foraging, probing muddy bottoms for crayfish, aquatic insects, and small fish.

You’ll find these florida bird species in both coastal and inland wetlands, where their Ibis Habitat includes marshes, swamps, and urban parks.

Their Ibis Diet consists primarily of crustaceans during breeding season, making them excellent indicators of wetland health.

White Ibis demonstrate fascinating Ibis Behavior, foraging in flocks of twenty or more birds.

Bird Conservation efforts focus on protecting their nesting colonies and foraging grounds throughout South Florida’s diverse ecosystems.

The urbanization of these birds is linked to changes in urban habitat use patterns, affecting their behavior and ecology.

Limpkin

This peculiar wading bird stands out among Florida’s wetland residents with its distinctive appearance and specialized hunting skills.

You’ll recognize the Limpkin by its brown, streaked plumage and slightly curved bill, perfectly designed for its unique diet. Unlike other Florida birds with long beaks, this species has evolved an exclusive relationship with apple snails.

- Limpkin Habitat: You’ll find these wading birds in freshwater marshes, swamps, and slow-moving rivers throughout Florida

- Limpkin Diet: They’re specialists, feeding almost exclusively on apple snails using their curved bills to extract meat

- Limpkin Behavior: These bird species are most active at dawn and dusk, often heard before seen

Wetland ecosystems support stable Limpkin populations, though bird conservation efforts remain essential for protecting their specialized niche.

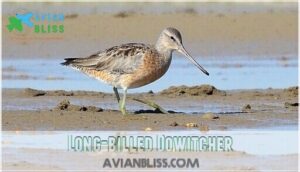

Long-billed Dowitcher

You’ll spot long-billed dowitchers working Florida’s mudflats like feathered sewing machines, their 2.5-3 inch beaks probing relentlessly for invertebrates.

These Florida shorebirds showcase remarkable beak functions, using their slightly curved bills to extract crustaceans and mollusks from coastal mud.

Their migratory patterns bring them through Florida during peak migration in July, following established flyways along both coasts.

| Characteristic | Details |

|---|---|

| Beak Length | 2.5-3 inches, slightly curved |

| Feeding Habits | Probes mud for invertebrates |

| Habitat Preferences | Coastal mudflats, shallow waters |

| Migration Timing | Peak July migration |

| Conservation Status | Monitored through shorebird plans |

Dowitcher conservation efforts focus on protecting these critical stopover sites that sustain long-beaked Florida birds during their incredible journeys.

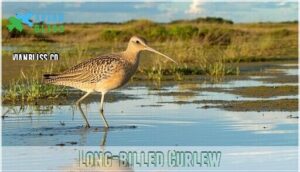

Long-billed Curlew

You can’t miss the Long-billed Curlew’s signature curved bill that stretches up to 8.5 inches – perfect for reaching deep into sandy beaches and mudflats.

This cinnamon-colored giant stands as North America’s largest shorebird, with distinctive mottled brown plumage and long legs built for wading.

Curlew Habitat spans from coastal marshes to inland prairies.

Migration Patterns bring these impressive Florida shorebirds to the Gulf Coast each winter, traveling from breeding grounds across the northern Great Plains.

Their Beak Function allows precise probing for marine worms, crabs, and mollusks buried in soft sediments.

Feeding Habits involve methodical sweeping motions through shallow water and mud.

Unfortunately, the Longbilled Curlew’s Conservation Status reflects declining populations due to habitat loss.

Watch for their distinctive flight pattern – those cinnamon underwings flash brilliantly against Florida’s winter skies, making identification easy for birders exploring various bird beak types among Florida birds.

Black-necked Stilt

Moving from the curlew’s probing technique, you’ll find the black-necked stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) equally fascinating among Florida’s wading birds.

This striking shorebird stands out with its impossibly long pink legs and needle-thin black beak – perfectly designed for hunting in shallow waters.

Black-necked stilts showcase remarkable beak adaptation for capturing small fish, crustaceans, and aquatic insects. Their bird behavior includes methodical wading through wetlands, using their sensitive bills like underwater tweezers.

These Florida shorebirds depend heavily on wetland ecology for survival, making habitat conservation critical for their future. Effective shorebird habitat management is essential to preserve their populations.

Key Black-necked Stilt Features:

- Distinctive appearance – Black and white plumage with disproportionately long red legs

- Specialized feeding – Needle-like beak perfect for precise prey capture

- Wetland dependency – Constructed wetlands provide 91% of nesting sites

- Stilt migration patterns – Seasonal movements between breeding and wintering grounds

Willet

The Willet’s distinctive long, straight beak makes it a standout among Florida shorebirds.

You’ll find these large, mottled brown-gray birds probing sandy beaches and mudflats with their specialized bills, hunting for crabs, marine worms, and mollusks.

Their Willet Diet includes small fish and aquatic invertebrates they extract from wet sand.

Willet Habitat spans Florida’s coastlines year-round, though some populations participate in Willet Migration between breeding grounds in prairie wetlands and wintering areas along the Gulf and Atlantic shores.

Their Willet Behavior includes territorial displays and loud, piercing calls that echo across the shoreline.

- Feeding technique: Willets use their long beaks to probe 2-3 inches deep into sand

- Flight pattern: Distinctive black-and-white wing stripes become visible during flight

- Social structure: Often feeds alone but roosts in small groups

Willet Conservation efforts focus on protecting coastal nesting sites from human disturbance and development pressures.

Whimbrel

Wherever shorebirds gather along Florida’s coast, you’ll find the Whimbrel standing out with its distinctive downward-curved beak.

This remarkable bird species showcases one of nature’s most specialized tools—their long beaks function perfectly for probing deep into muddy substrates.

Whimbrel migration patterns bring these Arctic breeders to Florida’s shores each winter, where their feeding habits focus on extracting fiddler crabs, marine worms, and mollusks from tidal flats.

These Florida birds prefer sandy beaches and mud flats as their primary habitat preferences.

Watch them stride methodically across the shoreline, using their curved bills like surgical instruments.

While their conservation status remains stable, continued habitat protection guarantees future generations can witness these incredible shorebirds.

American Oystercatcher

You’ll spot American Oystercatchers strutting along Florida’s sandy beaches with their unmistakable bright orange beaks cutting through the coastal breeze.

These stocky Florida shorebirds pack serious attitude into their black-and-white tuxedo plumage, standing nearly two feet tall with beaks perfectly designed for their shellfish obsession.

Their specialized beak function revolves around one thing: cracking open oysters, mussels, and clams with surgical precision. Watch their feeding habits in action as they use that knife-like bill to pry apart shells or probe sandy substrates for hidden treasures.

Oystercatcher habitat centers on undisturbed beaches and tidal flats where they establish nesting sites in simple scrapes above the high-tide line. Unfortunately, their conservation status reflects mounting pressures from coastal development and human disturbance.

These Florida birds with long beaks face challenges as beachfront construction eliminates critical breeding areas, making every sighting of these charismatic bird species increasingly precious.

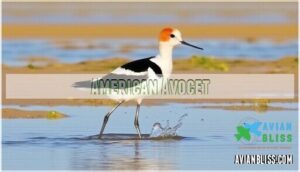

American Avocet

With their elegantly upturned beaks sweeping through shallow waters like nature’s own vacuum cleaners, American Avocets showcase one of the most distinctive Beak Functions among Florida birds.

You’ll recognize these striking waders by their black-and-white plumage and peachy-orange heads during breeding season. Their specialized long beaks allow precise Feeding Habits as they wade through salt ponds and mudflats, capturing small crustaceans and aquatic insects.

Key identification features include:

- Thin, recurved bills perfect for shallow-water foraging

- Bold black wing stripes visible in flight

- Loud, melodic "kleet-kleet" calls

While their Migration Patterns bring them through Florida seasonally, their Conservation Status remains stable thanks to protected Avocet Habitat areas along coastal marshes.

Roseate Spoonbill

Why do Roseate Spoonbills sweep their distinctive bills side-to-side through shallow water? This unique Beak Function allows these Florida shorebirds to filter small fish, crustaceans, and aquatic insects from murky coastal waters.

You’ll find these pink-plumed Florida birds with long beaks wading through mangrove lagoons and tidal flats, using their spatulate bills as natural sieves. Their Spoonbill Habitat includes coastal wetlands, brackish ponds, and mudflats throughout South Florida.

These Roseate Spoonbill birds demonstrate fascinating Feeding Habits, stirring sediment with their feet while sweeping their specialized beaks through the water column. During breeding season, their Nesting Behavior involves building stick platforms in mangrove colonies.

Recent surveys show concerning population declines, making their Conservation Status a priority for wildlife managers. You’ll spot these remarkable birds year-round in places like Everglades National Park and Florida Bay.

Great Egret

Standing four feet tall with snowy white plumage, the Great Egret commands attention in Florida’s wetlands.

You’ll recognize this majestic wader by its bright yellow beak and distinctive black legs.

Unlike the White Ibis with its curved bill, the Great Egret’s straight, dagger-like beak functions perfectly for spearing fish, frogs, and small reptiles in shallow waters.

This impressive hunter employs a patient "wait-and-strike" technique, remaining motionless before lightning-fast strikes.

Great Egrets inhabit diverse environments from coastal marshes to freshwater ponds, adapting their hunting strategies accordingly.

- Egret Habitat: Prefers shallow waters under three feet deep for ideal fishing

- Beak Function: Sharp, pointed bill delivers precise strikes to capture slippery prey

- Feather Care: Spends hours preening to maintain waterproof plumage

- Nesting Sites: Builds stick platforms in tall trees near water sources

Snowy Egret

When you encounter Florida’s pristine wetlands, the Snowy Egret stands out like a white beacon among the marshes.

This elegant wader uses its thin yellow bill to spear fish, frogs, and aquatic insects with lightning-fast precision.

Unlike the larger Great Egret, Snowy Egrets display distinctive black legs with bright yellow feet that birders call "golden slippers."

- Egret Habitat: Thrives in both freshwater marshes and saltwater estuaries throughout Florida year-round

- Feeding Behavior: Employs active hunting techniques, stirring sediment with feet to flush out hidden prey

- Nesting Sites: Breeds in mixed colonies alongside White Ibis and Roseate Spoonbill in cypress swamps and mangroves

Their Conservation Status improved dramatically after near-extinction from plume hunting in the 1800s.

Today’s stable populations don’t follow strict Migration Patterns like the Longbilled Dowitcher, making them reliable residents you’ll spot during any season.

Great Blue Heron

You’ll spot the Great Blue Heron standing motionless like a statue in Florida’s shallow waters, its steel-blue feathers catching sunlight.

This magnificent bird towers over other florida shorebirds, reaching four feet tall with a six-foot wingspan.

Watch as it demonstrates patience that’d make a meditation guru jealous, waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

The Great Blue Heron‘s dagger-sharp bill spears fish, frogs, and small reptiles with surgical precision.

Their Heron Diet includes anything from minnows to small mammals.

These heron birds prefer Heron Habitat along coastlines, marshes, and mangroves for hunting.

During breeding season, they gather at communal Nesting Sites in tall trees, building stick platforms twenty feet high.

Their Flight Patterns show slow, powerful wingbeats as they patrol waterways searching for their next meal.

Little Blue Heron

While Great Blue Herons command attention with their impressive size, the Little Blue Heron offers a more intimate birding experience.

You’ll find these elegant florida waterbirds year-round in Florida’s marshes and mangroves, their slate-blue feathers creating perfect camouflage among shadowy waters. Don’t let their name fool you – adults display stunning blue-gray plumage that’s anything but little in impact.

Watch their patient Heron Behavior as they wade through shallow Heron Habitat, using their long beaks to spear fish, frogs, and crustaceans. Their Heron Diet consists mainly of small aquatic prey they capture with lightning-quick strikes.

These florida shorebirds breed in mixed colonies, building platform nests in trees. During Bird Migration periods, you might spot larger flocks gathering. Young birds start white before developing their signature Blue Feathers, making identification tricky for beginning birders.

Understanding their unique heron habitat needs is essential for conservation efforts and appreciating these birds in their natural environment.

Tricolored Heron

While Little Blue Herons prefer shallow freshwater areas, the Tricolored Heron stakes out deeper brackish waters along Florida’s coast.

You’ll recognize this elegant wader by its distinctive slate-blue head, purple chest, and striking white belly stripe.

During Heron Migration season, watch for its unique hunting style – it crouches low before striking with lightning speed.

The Tricolored Habitat spans saltmarshes and mangrove swamps where its needle-sharp beak excels at spearing small fish.

Feather Colors intensify during breeding when males develop bright blue facial skin.

Their Nesting Habits include building platform nests in mixed colonies, and their Beak Functions perfectly for active foraging in Florida’s diverse wetlands.

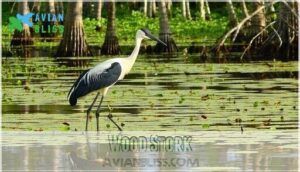

Wood Stork

You’ll recognize Wood Storks by their distinctive bald heads and massive bills as they wade through Florida’s shallow waters.

These impressive wading birds represent one of Florida’s most important bird conservation success stories, though they remain threatened.

Wood Stork Habitat centers on shallow freshwater wetlands where fluctuating water levels concentrate prey like fish and frogs.

Their specialized Stork Feeding technique involves tactile probing—they can’t see underwater, so they rely on touch to snap up prey.

Here’s what makes Wood Storks remarkable:

- Colony nesters – They gather in cypress swamps and mangroves during February-July breeding season

- Tactical hunters – Their bills snap shut in 25 milliseconds when detecting fish

- Wetland indicators – Their presence signals healthy Wetland Ecology

These Florida birds demonstrate nature’s incredible adaptation to specialized environments.

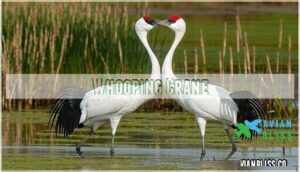

Whooping Crane

Standing nearly five feet tall, the Whooping Crane represents one of conservation’s greatest success stories among Florida birds with long beaks.

This endangered species dropped to just 15 individuals in 1941, but dedicated crane conservation efforts have rebuilt populations to over 500 today.

You’ll find these majestic Florida wildlife residents in wetlands from October through March, their trumpet-like calls echoing across preserved marshes.

Habitat loss and development threaten their survival, making wetland preservation essential.

During bird migration seasons, watch for their distinctive red crowns and seven-foot wingspans at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge.

American White Pelican

While whooping cranes capture attention with their striking calls, American White Pelican steals the show with Florida’s longest beak—exceeding 15 inches.

You’ll spot these massive birds during pelican migration from northern breeding grounds to Florida’s warm waters.

Their beak function goes beyond impressive size; it’s a perfect scoop for cooperative feeding habits where flocks work together herding fish into shallow water.

Unlike other Florida birds with long beaks, these pelicans don’t dive-bomb their prey, instead, they swim and dip gracefully.

Conservation status remains stable, though nesting sites require protection from human disturbance and habitat loss.

Brown Pelican

The Brown Pelican’s massive beak and expandable throat pouch make it Florida’s most recognizable diving bird.

You’ll spot these coastal giants plunge-diving headfirst into shallow waters, scooping up fish with incredible precision. Their distinctive fishing technique sets them apart from other Florida birds with long beaks.

Here’s what makes Brown Pelicans special:

- Beak Function: Their 13-inch bill features a stretchy pouch that holds up to three gallons of water

- Feeding Habits: They dive from 20-60 feet high, stunning fish with impact before surfacing to drain water

- Pelican Habitat: Coastal waters, mangroves, and sandy beaches throughout Florida year-round

- Conservation Status: Successfully recovered from near-extinction, now thriving with stable populations

These remarkable Florida bird species demonstrate nature’s engineering prowess. Their synchronized fishing displays and graceful soaring make them favorites for Florida bird identification enthusiasts seeking authentic coastal wildlife experiences.

Black Skimmer

You’ll spot the Black Skimmer’s distinctive red-and-black scissor-like beak cutting through coastal waters like a precision tool.

This remarkable bird species showcases unique Beak Functions among Florida birds, using its knife-thin lower mandible to slice through water while hunting.

Unlike other long beaks designed for probing, the skimmer’s specialized design enables incredible Feeding Tactics—you’ll watch it fly low, dragging its beak through shallow water to snatch fish.

Black Skimmers prefer Skimmer Habitat along beaches, sandbars, and coastal lagoons throughout Florida’s shoreline.

These colonial nesters face significant conservation challenges from coastal development and human disturbance.

Skimmer Conservation efforts focus on protecting nesting sites during breeding season.

You’ll find them year-round in Florida, though populations fluctuate with Bird Migration patterns.

Their synchronized feeding flights create mesmerizing displays as groups work together.

Ruby-throated Hummingbird

During spring and fall migrations, you’ll witness the ruby-throated hummingbird‘s incredible journey as this tiny Florida bird species travels 500 miles nonstop across the Gulf of Mexico.

This remarkable member of Florida avian life showcases perfectly adapted long beaks designed for accessing tubular flower nectar with surgical precision.

The ruby-throated hummingbird‘s specialized features make it unforgettable:

- Beak Structure: Needle-thin bill perfectly matches trumpet vine and cardinal flower openings

- Feather Colors: Males display brilliant ruby-red throat patches that shimmer like jewels in sunlight

- Flight Patterns: Wings beat 80 times per second, allowing backwards and upside-down maneuvers

- Nesting Habits: Females weave walnut-sized nests using spider silk and plant down

During hummingbird migration periods, you’ll spot these aerial acrobats hovering at feeders and native blooms throughout Florida’s gardens and natural areas.

Bird Identification Tools

When identifying Florida’s long-beaked species, you’ll need reliable tools that capture subtle differences in beak shapes and plumage colors.

Quality binoculars reveal wing tips and feather patterns that distinguish similar species. The Merlin Bird ID app excels at bird calls recognition, while Peterson and Sibley field guides provide detailed illustrations for florida bird identification.

eBird helps track bird species locations across florida birds hotspots. For bird watching florida enthusiasts, combine multiple resources—apps can identify long beaks instantly, but field guides teach you the "why" behind each identification feature.

Investing in good birding optics substantially enhances the birding experience.

Birding Locations in Florida

You’ll find Florida’s long-beaked birds across diverse ecosystems, from the Everglades’ freshwater marshes where White Ibis probe for crustaceans to Sanibel Island’s beaches where American Oystercatchers pry open shellfish.

The state’s year-round warm climate and abundant wetlands create ideal conditions for spotting species like Roseate Spoonbills in Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge and Wood Storks in Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, which are key to the ecosystem’s biodiversity.

Best Time for Birding

After you’ve mastered bird identification tools, timing becomes everything for successful florida birds with long beaks encounters.

Weather patterns and seasonal migration cycles determine peak activity periods throughout the year.

Optimal Birding Times:

- Early morning hours (5:30-9:00 AM) – Peak activity for feeding behaviors

- Late afternoon (4:00-6:30 PM) – Second feeding period begins

- Spring migration (April 19-May 7) – Highest species diversity window

- Winter months (December-February) – Florida bird species concentrate in warmer habitats

- Overcast days – Enhanced bird watching in Florida visibility conditions

Habitat conditions improve dramatically during cooler temperatures when florida birding tours report maximum sightings.

Effective bird watching requires the right bird watching gear to enhance the overall experience.

Top Birding Spots

Where will you find Florida’s most spectacular long-beaked birds?

Everglades Tours reveal wood storks and herons along pristine wetland trails, while coastal birding at Huguenot Memorial Park showcases 237 species.

Nature reserves like Wakodahatchee Wetlands offer close encounters with ibises and spoonbills.

Bird sanctuaries including Ding Darling provide guaranteed sightings.

These florida birdwatching spots transform casual observers into passionate birders.

Many enthusiasts rely on effective Florida birding equipment to enhance their experiences.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do long beaks help birds survive?

Picture a heron’s dagger-like bill piercing murky water with surgical precision.

You’ll see how these specialized tools let birds reach deep crevices, probe muddy substrates, and capture elusive prey that shorter-beaked competitors simply can’t access.

This allows them to utilize their specialized tools in a unique way.

What threatens Floridas long-beaked bird populations?

Habitat loss, pollution, and climate change pose major threats to you’ll observe in Florida’s wetlands.

Development destroys nesting sites, while pesticides contaminate food sources.

Rising sea levels flood coastal breeding areas, forcing these specialized feeders to relocate due to habitat loss.

Which species migrate versus year-round residents?

Roughly 60% of Florida’s long-beaked birds migrate seasonally. You’ll spot American White Pelicans and Long-billed Dowitchers during winter months, while White Ibis, Limpkins, and Brown Pelicans call Florida home year-round.

How do weather patterns affect feeding habits?

Weather patterns dramatically shift your local long-beaked birds’ feeding routines.

During storms, they’ll seek sheltered areas and switch prey types.

Droughts concentrate fish in smaller water bodies, creating feeding bonanzas that alter their usual foraging schedules.

What conservation efforts protect endangered species?

Like guardian angels watching over fragile populations, you’ll find habitat restoration projects, captive breeding programs, and protected reserves safeguarding species like Florida’s critically endangered Whooping Crane.

These efforts ensure these magnificent birds don’t vanish forever, highlighting the importance of conservation through habitat restoration.

Conclusion

Frankly, you’ve now mastered identifying Florida’s most dramatically beaked residents—no more confusing spoonbills with herons or mistaking stilts for dowitchers.

These florida birds with long beaks aren’t just showing off their impressive bills for vanity; each specialized tool represents millions of years of evolutionary fine-tuning.

Whether you’re spotting curved ibis bills probing mudflats or watching pelicans plunge-dive with surgical precision, you’ll appreciate how form perfectly follows function in Florida’s remarkable wetland ecosystems.