This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

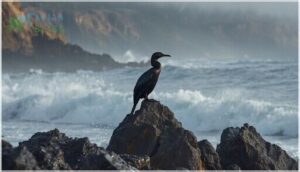

The pelagic cormorant doesn’t look like much from shore—just another dark silhouette perched on a cliff face or diving through cold Pacific swells. But this sleek seabird has mastered one of the ocean’s toughest neighborhoods.

While other cormorants spread across diverse habitats, this species commits entirely to exposed coastlines from Alaska to Baja California, thriving on rocky outcrops that few birds can tolerate. Its slender build and remarkable diving ability allow it to plunge nearly 140 feet below the surface, hunting fish and crustaceans in kelp forests and nearshore reefs.

You’ll find these cormorants returning to the same nesting sites year after year, building their lives on narrow cliff ledges where wind and waves dominate the landscape.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Pelagic Cormorant Physical Characteristics

- Habitat and Geographic Range

- Diet and Foraging Behavior

- Breeding and Life Cycle

- Conservation Status and Threats

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- How do you identify a Pelagic Cormorant?

- What are some interesting facts about pelagic cormorants?

- Is a double crested cormorant the same as a Pelagic?

- How deep can a Pelagic Cormorant dive?

- How long do pelagic cormorants typically live?

- What are their main vocalizations or calls?

- Do pelagic cormorants migrate seasonally?

- How do they interact with other seabird species?

- What role do they play in coastal ecosystems?

- What sounds or calls do they make?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- You’ll find pelagic cormorants thriving exclusively along exposed Pacific coastlines from Alaska to Baja California, where their slender build and ability to dive nearly 140 feet deep allow them to hunt fish and crustaceans in rocky kelp forests that few other seabirds can access.

- These birds show remarkable nest site fidelity, with over 92% returning to the same cliff ledge locations within 25 centimeters year after year, building their nests from sea grasses cemented with guano on steep, predator-resistant coastal cliffs.

- While the species maintains a “Least Concern” conservation status globally, regional populations have declined significantly—particularly a 66% drop in British Columbia since the 1970s—driven by oil spills, coastal development, and human disturbance that can trigger near-total colony abandonment.

- Pelagic cormorants play a vital ecological role in coastal ecosystems through nutrient cycling from their guano deposits and by regulating marine prey populations, making them reliable indicators of overall ocean health along the Pacific coast.

Pelagic Cormorant Physical Characteristics

You’ll recognize a pelagic cormorant by its sleek, all-black body and surprisingly slender build compared to other cormorants along the Pacific coast. These birds aren’t particularly large, but their long necks and narrow heads give them a distinctive profile when perched on rocky outcrops or flying low over the waves.

Let’s look at the specific physical features that set this species apart.

Body Size and Shape

You’ll notice the pelagic cormorant has a slender build that sets it apart. Body size ranges from 20 to 35 inches in length, with a wingspan reaching about 39 to 48 inches. Weight measurements fall between 48 and 86 ounces. Sexual dimorphism is minimal—males are slightly larger than females.

Key body proportions include:

- Long, thin neck for agile diving

- Narrow head relative to body size

- Wedge-shaped tail for sleek swimming

- Large, fully webbed feet positioned rearward

- Slender frame optimized for marine adaptations

Juveniles appear smaller with duller brown plumage, while breeding plumage adults develop head crests that accentuate their shape. They’re known to forage by diving from the surface, often in rocky areas.

Plumage and Seasonal Changes

You’ll see striking seasonal coloration shifts in pelagic cormorants throughout the year. Breeding plumage displays iridescent green and violet-bronze hues with white flank patches and red facial skin. The molting process spans over 200 days, beginning in late summer. Nonbreeding adults revert to duller gray-black tones.

Regional variation exists—southern populations retain breeding features longer than northern migratory birds, providing plumage camouflage against rocky coasts. They’re commonly found near Haystack Rock.

Bill, Feet, and Tail Features

Beyond those seasonal color changes, you’ll notice the pelagic cormorant’s slender bill—thinner than other Pacific cormorants—measures 4–6 cm and turns vivid magenta near the eye during breeding.

Their large, fully webbed feet power dives exceeding 30 meters. The wedge-shaped tail, comprising 12–14 stiff feathers, accounts for 25% of body length.

These hydrodynamic adaptations enable precision hunting in coastal waters.

Comparison With Other Cormorant Species

When you’re trying to identify pelagic cormorants among other North American species, size differences matter. At 25–30 inches, they’re smaller and slimmer than bulky Brandt’s cormorants (33–35 inches).

Key plumage variations include:

- Breeding pelagics show glossy green-purple with red throat patches

- Double-crested cormorants develop side head tufts

- Juvenile pelagics stay uniformly dark brown

- Brandt’s display blue throat patches

Colony size also varies—pelagics favor isolated pairs versus crowded Brandt’s colonies.

Habitat and Geographic Range

You’ll find pelagic cormorants along the Pacific coast, where rocky shores and open waters meet. These birds stick close to land, never straying far from the coastal environments they depend on.

Understanding where they live and how far they travel reveals the unique lifestyle of this slender seabird.

Coastal and Marine Environments

You’ll find pelagic cormorants thriving along rocky coasts and marine environments from Alaska to Baja California. These birds rarely venture inland, preferring steep cliffs, narrow ledges, and offshore islands where human disturbance stays minimal.

Coastal habitat degradation, marine pollution, and climate change threaten their preferred zones—coastal bays, estuaries, and kelp-rich waters teeming with marine life.

| Habitat Feature | Cormorant Use |

|---|---|

| Rocky headlands | Roosting and perching sites |

| Coastal cliffs | Primary nesting locations |

| Kelp beds | Foraging grounds for fish |

| Estuaries & lagoons | Feeding during non-breeding season |

Conservation efforts now focus on protecting these coastal regions from development and environmental hazards.

Breeding Grounds and Nesting Sites

You’ll discover pelagic cormorants nesting on narrow ledges of steep sea-facing cliffs, where protection from predators runs high. Their colony site fidelity is striking—over 92% of nest sites shift less than 25 centimeters between years.

Nest building involves grass and seaweed, with males initiating construction. Breeding colony density varies widely, from dozens to thousands of nests depending on location.

Fledgling success rates fluctuate dramatically based on environmental conditions and nest site protection.

Migration Patterns and Local Movements

You’ll notice distinct pelagic cormorant migration patterns depending on latitude. Subarctic populations migrate roughly 600 to 1,190 kilometers south each fall, generally reaching southeast Alaska and British Columbia within five days. Meanwhile, temperate populations disperse locally rather than undertaking long flights.

Site fidelity remains strong—tagged birds return to the same 10-kilometer winter radius annually. Temperature shifts and declining fish abundance trigger these seasonal movements.

Distribution From Alaska to Baja California

You’ll find pelagic cormorant distribution stretching over 100,000 square kilometers from Alaska’s Arctic waters to Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula. Approximately 50,000 breed in Alaska and offshore islands, while 25,000 nest along the Pacific coast outside Alaska—60% in California alone.

Regional migration patterns shift with climate impacts, increasing coastal habitat use in southern California and Baja during winter as northern breeding grounds freeze.

Diet and Foraging Behavior

The pelagic cormorant is a specialized hunter that relies on its diving ability to catch food beneath the ocean’s surface.

You’ll find these birds feeding on a varied diet that changes based on what’s available in their coastal waters. Let’s look at what they eat, how they hunt, and where they prefer to forage throughout the year.

Primary Food Sources and Prey

You’ll find pelagic cormorants consuming a diverse menu of marine prey. Fish dominate their diet, including Pacific herring, sandlance, sculpin, rockfish, and flatfish juveniles. Crustaceans like crabs and shrimp supplement their food sources, along with marine worms and amphipods.

Their foraging habitat influences prey selection greatly—nearshore rocky reefs and kelp forests provide access to both benthic and mid-water species, creating diet variation across their geographic range.

Diving Depths and Foraging Techniques

When you watch pelagic cormorants hunt, you’re seeing masters of underwater propulsion. Their maximum dive reaches 138 feet, with some birds staying submerged over two minutes. They kick rapidly with webbed feet for thrust while wings stabilize their descent.

Prey detection relies on sharp vision in dim waters. These diurnal patterns show most foraging occurs during daylight, with energetic efficiency optimized through their specialized diving and feeding behavior.

Feeding Habitat Preferences

Rocky shorelines define where pelagic cormorants feed. You’ll find them along steep cliffs and boulder-strewn coasts, diving over subtidal rocky bottoms rather than flat sand. Their habitat specificity ties directly to prey availability among rock crevices.

Most foraging happens within 9 km of nesting colonies, with 93% of birds returning to the same 6 km² feeding zone repeatedly throughout chick-rearing season.

Seasonal Variations in Diet

Your pelagic cormorant’s diet shifts dramatically with the calendar. Winter prey leans toward sticklebacks and juvenile sculpins, while spring composition brings larger rockfish and greenlings. Breeding diet peaks with fish over 20 cm long. Oceanic influence matters too—El Niño years reduce prey abundance and breeding success. Regional variation is significant:

- Winter: 60% small fish like sticklebacks

- Spring: 45% larger prey species

- Summer: 40% young flatfish and anchovy

- Crustaceans peak at 18% in late spring

- Daily dives drop from 80+ in summer to under 40 in winter

Feeding habits adapt constantly to what’s available.

Breeding and Life Cycle

Pelagic cormorants follow a fascinating reproductive cycle that plays out on rocky coastal cliffs each year. From selecting the perfect nest site to raising their chicks, these birds show considerable dedication to their offspring.

Let’s look at the key stages that define their breeding behavior and life cycle.

Nest Building and Site Selection

With surgical precision, nesting Pelagic Cormorants select specific cliffside ledges year after year. Studies reveal 92% nest site fidelity within 25 centimeters over ten years, showcasing striking memory. You’ll find their nests constructed from sea grasses, bonded with guano to steep rock faces. These nesting sites cluster in colonies on inaccessible cliff ledge characteristics, optimizing protection from predators while maximizing limited space.

| Nesting Behavior | Key Details |

|---|---|

| Nest construction materials | Sea grasses secured with feces |

| Nesting activity patterns | Peak building: May–July annually |

| Colony structure | Dense aggregations on favored ledges |

Egg Laying and Incubation Period

Once nests are secured, you’ll notice females begin egg laying from mid-May through mid-June. The clutch generally contains three bluish-white eggs laid at two-day laying intervals. Both parents share incubation duties over a 31-day incubation period, alternating places 3-5 times daily. This hatching asynchrony creates size differences among chicks.

- Egg incubation period averages 31 days with parental vigilance throughout

- Clutch composition ranges from one to five eggs per nest

- Incubation exchanges occur multiple times daily between both parents

Parental Care and Chick Development

After hatching, you’ll observe both parents share feeding duties and nest attendance throughout chick development. Young nestlings weigh just 35 grams but rapidly grow with frequent parental provisioning.

Feeding frequency stays high as chicks develop sooty-gray down. Energy expenditure varies yearly based on environmental conditions.

Most fledglings take their first flights at 35-40 days, with typical fledging occurring between 45-55 days despite survival factors affecting final numbers.

Breeding Season Timing and Colony Structure

From late April through August, you’ll find breeding adults establishing territories at colony sites along the Pacific coast. Nesting site fidelity runs strong—over 90% of pairs return to previous locations year after year.

Colonies fluctuate considerably in size, from small groups to aggregations exceeding 100 pairs. Clutch size variation ranges from one to five eggs, with breeding asynchrony creating staggered hatching across the colony.

This spatial nesting structure reflects available cliff ledge topography.

Conservation Status and Threats

The pelagic cormorant currently holds a classification of Least Concern by the IUCN, thanks to its wide range and stable global population. However, this doesn’t mean the species is free from danger.

Both human activities and environmental hazards pose real risks to local colonies and nesting success.

Population Trends and IUCN Classification

You might be surprised to learn that despite decades of declines, the Pelagic Cormorant population still earns a “Least Concern” conservation status from the IUCN. Here’s what the numbers tell us about this species’ standing:

- Global population size exceeds 100,000 breeding individuals across Pacific coastal regions

- Population declines of 25% since the 1970s occurred primarily during the 1990s

- Regional variations show severe losses in British Columbia (66% decline) while Alaska remains stable

- Future projections suggest recovery to 1970s levels by 2050 if conservation efforts address key threats

The IUCN criteria focus on range-wide trends rather than localized drops. While conservation status and population dynamics reveal concerning patterns in the Pacific Northwest, the species’ extensive distribution prevents a higher threat classification under current assessment standards.

Human Disturbance and Habitat Loss

Human disturbance can hit Pelagic Cormorant colonies hard, and coastal development doesn’t help. Urban encroachment has wiped out over 65% of breeding sites near major centers since the 1970s. Boat traffic and fishing impacts trigger colony abandonment—one event saw numbers plummet from 1,900 to just 13 birds. Legal protection and restoration efforts show promise, with controlled access doubling chick survival at managed sites.

| Threat Type | Impact on Colonies | Conservation Response |

|---|---|---|

| Urban encroachment | 65% breeding site loss near cities | Habitat restoration at 80% of sites |

| Boat and fishing traffic | 90%+ nest abandonment rates | Visual barriers, access control |

| Human presence on cliffs | 50% reduction in nesting pairs | Legal protection during breeding season |

Oil Spills and Environmental Hazards

Oil spills devastate Pelagic Cormorant populations through acute and chronic oil exposure. The Exxon Valdez spill killed up to 8,800 cormorants, and community-wide trends show spill mortality rates consistently hit coastal ecosystems hard.

Oil spills devastate pelagic cormorant populations, with the Exxon Valdez alone killing up to 8,800 birds

Chronic oil exposure accounts for 1–4% of annual deaths in some regions. Contaminant accumulation affects chick health.

Rehabilitation efforts help, but recovery takes decades. Conservation must address these threats to protect marine environment populations.

Natural Predators and Mortality Factors

Bald eagles rank among the most dangerous avian predators to adult Pelagic Cormorants, while gulls and crows target vulnerable eggs and chicks. Chick mortality reaches 25–48% between hatching and fledging, driven by predation, starvation, and sibling competition.

Human disturbance amplifies these threats, causing up to 49% of losses in some colonies. Parasite impacts remain minimal, but adult survival exceeds 80% annually despite these conservation status and threats.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do you identify a Pelagic Cormorant?

You can spot this seabird by its slender neck and small head, measuring 25–30 inches with glossy black plumage.

During breeding season, look for white thigh patches and magenta facial skin below the eye.

What are some interesting facts about pelagic cormorants?

You’ll spot these sleek seabirds plunging nearly 180 feet beneath cold Pacific waves, their iridescent black feathers shimmering like polished obsidian.

They’ve mastered underwater hunting, can live almost 18 years, and build nests cemented with their own guano.

Is a double crested cormorant the same as a Pelagic?

No, these are distinct species from different genera. Double-crested cormorants are larger with orange facial patches, while pelagic cormorants are smaller, slenderer, and display white flank patches during breeding season.

How deep can a Pelagic Cormorant dive?

You might think diving birds stick to shallow waters, but the Pelagic Cormorant defies expectations.

This underwater swimming specialist can plunge to depths of 138 feet while foraging for fish and crustaceans along rocky coasts.

How long do pelagic cormorants typically live?

You’ll usually find pelagic cormorants living 15 to 20 years in the wild. The longest verified pelagic cormorant lifespan reached nearly eighteen years, though most don’t survive past their late teens due to environmental pressures.

What are their main vocalizations or calls?

You’ll hear simple groaning and hissing breeding calls from males, while females produce clicking sounds near nests. Outside breeding season, Pelagic Cormorants stay silent—unlike their noisier cormorant cousins.

Do pelagic cormorants migrate seasonally?

You’ll see regional differences in movement, not textbook migration. Northern populations abandon icy breeding sites in Alaska each winter, traveling up to 1,190 km southward, while temperate-zone birds remain year-round residents.

How do they interact with other seabird species?

Seabird colonies often bring mixed species together. Pelagic Cormorants share nesting sites with Brandt’s Cormorants and gulls, creating foraging competition and nest aggression.

Spatial segregation on cliff ledges reduces conflict, while predator dynamics shape survival rates.

What role do they play in coastal ecosystems?

You’ll find these birds enriching coastal habitats through nutrient cycling from their guano, regulating prey populations through daily consumption of fish and invertebrates, and serving as reliable indicators of marine ecosystem health.

What sounds or calls do they make?

Ever wonder how silent seabirds communicate? Pelagic Cormorant vocalization includes guttural grunts, groans, and purrs during courtship display.

Males produce unique calls for avian behavior coordination, while acoustic communication intensifies at breeding colonies, showcasing distinct sound variations.

Conclusion

You’ve seen how the pelagic cormorant thrives where others can’t—on wind-battered cliffs, in frigid waters, beneath kelp canopies most birds never reach. You’ve learned what it eats, how it raises its young, and what threatens its survival.

Now you understand why this sleek diver commands respect. It doesn’t adapt to the coast. It belongs there. And recognizing that difference means you’re not just observing seabirds anymore—you’re reading the ocean itself.

- https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/pelagic-cormorant

- https://www.nps.gov/places/pelagic-cormorant.htm

- https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/esr.do;jsessionid=sMvvWvPb1CKx3sfs2KyCYs9KNtWJz882n3JqsGSV22B1vLGml8vn!711369738?id=17703

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelagic_cormorant

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Pelagic_Cormorant/lifehistory