This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

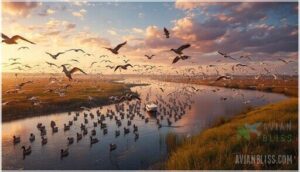

Birds don’t simply wander; they follow precise aerial highways shaped by millions of years of evolution, continental geography, and the planet’s magnetic fields. Understanding the types of bird migration routes reveals how over 4,000 species navigate between breeding and wintering grounds through distinct flyways, employ intricate orientation strategies from star patterns to olfactory maps, and adapt their movements across latitudinal, longitudinal, and altitudinal gradients.

These migration corridors—whether spanning continents or mountain slopes—represent some of nature’s most notable feats of endurance and navigation.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Bird Migration Basics

- Major Flyways Routes

- Navigation Methods Used

- Migration Patterns Types

- Global Migration Routes

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are the major migration routes for birds?

- What are the 8 major migratory bird flyways?

- What are the four flyways?

- What is the word for a bird migration route?

- How do birds know when to start migrating?

- What happens when migration routes get blocked?

- Do young birds learn migration from parents?

- How does climate change affect migration timing?

- Why do some birds migrate at night?

- How do birds choose which route to take?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Birds navigate using a sophisticated combination of four primary methods—celestial navigation (star patterns and sun tracking), magnetic orientation via retinal cryptochrome proteins, visual landmark recognition of terrain features, and olfactory mapping of chemical gradients—with approximately 90% of nocturnal migrants relying on star patterns and birds deprived of smell failing homing attempts up to 80% of the time.

- The world’s major flyways form interconnected aerial highways supporting billions of migratory birds annually, including North America’s four corridors (Pacific, Central, Mississippi, Atlantic) and global routes like the East Asian-Australasian Flyway that connects 24 countries and supports over 50 million waterbirds, with critical stopover sites hosting densities exceeding 200,000 birds per square mile.

- Migration patterns span three distinct types based on distance and predictability: long-distance migrations like the Arctic Tern’s 90,000 km annual journey and Bar-tailed Godwit‘s nonstop 6,800 km Pacific crossing; short-distance movements under 1,000 km with flexible timing; and irregular irruptive migrations driven by food scarcity rather than photoperiod cues, with some populations expanding ranges by 800 kilometers during resource crashes.

- Climate change has fundamentally disrupted migration ecology, driving North American birds to shift wintering ranges over 200 miles northward since the 1970s at approximately 3.3 km per year, extending fall migration timing by 17 days, and creating phenological mismatches between bird arrivals and insect emergence that threaten survival rates across multiple flyways.

Bird Migration Basics

When you track the seasonal movements of birds, you’ll notice they don’t all follow the same compass. Migration takes three distinct directional forms, each shaped by geography, climate, and the resources birds need to survive.

Let’s explore how these fundamental patterns guide billions of birds across the globe each year.

Latitudinal Migration

Latitudinal migration, the most prevalent pattern among migratory species, describes north-south movements that follow temperature gradients across continents. These journeys are exemplified by birds traveling vast distances between breeding grounds in northern latitudes and wintering habitats farther south. Long-distance migration routes can exceed 70,000 km annually, as documented in Arctic Terns traveling between polar regions.

Latitudinal migration drives birds on north-south journeys across continents, with some species like Arctic Terns traveling over 70,000 km annually between polar extremes

Climate change has driven species to relocate northward at approximately 3.3 km per year, with 61% of North American birds shifting wintering ranges over 200 miles since the 1970s. Migration timing now extends 17 days longer in fall compared to four decades ago, reflecting species adaptation to warming conditions. Understanding the impact of climate change effects is vital for conservation efforts.

Four defining characteristics shape latitudinal migration patterns:

- Breeding latitude correlation – Northern-breeding species travel up to four times farther than temperate breeders

- Flyways utilization – Birds follow established migration routes spanning continents

- Photoperiod triggers – Migration timing corresponds to daylight thresholds rather than calendar dates

- Habitat conservation needs – Bird tracking reveals stopover sites critical for refueling during extended journeys

Longitudinal Migration

East-west movements define longitudinal migration, a strategy where species track precipitation gradients rather than temperature shifts. You’ll find this pattern most commonly among European birds like the Eurasian Blackcap, which covers 1,200 km between the UK and Eastern Europe. Climate adaptations increasingly drive these migration routes as habitat fragmentation alters traditional flyways—radiotelemetry reveals 19% increases in east-west deviations since 2010.

Geographic barriers such as mountain ranges and continental divides shape these migration patterns, forcing birds to develop flexible migration strategies that prioritize resource availability over latitudinal consistency, ultimately creating ecological impacts across diverse biomes. The study of bird migration patterns is essential to understanding these complex movements.

Altitudinal Migration

While latitudinal and longitudinal routes span continents, altitude shifts represent a distinctly vertical migration strategy. You’ll observe this pattern as birds ascend to high-altitude breeding sites during summer, then descend to lower elevations when winter arrives. Over 30% of montane forest species practice altitudinal migration, responding to climate impacts and migration triggers like temperature thresholds between 9.8°C and 13.9°C.

Understanding these elevation changes reveals notable species adaptation:

- Vertical movement generally spans 1,000–4,000 meters rather than horizontal distances

- Temperature and invertebrate biomass directly correlate with migration timing at elevation sites

- Southern Giant Hummingbirds travel 8,300 km with altitude shifts exceeding 4,100 meters

- Sex-biased patterns emerge, with males often remaining at breeding grounds while females migrate

- Flight altitudes range between 1.5–3 km, substantially lower than long-distance flyways

This migration pattern demonstrates how bird migration routes adapt to local terrain rather than continental-scale movements.

Major Flyways Routes

North America’s four major flyways—the Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic corridors—serve as aerial highways for millions of migrating birds each year. These routes, shaped by mountain ranges, coastlines, and river systems, guide diverse species between their breeding and wintering grounds.

Understanding each flyway’s unique characteristics reveals how birds navigate the continent’s varied landscapes.

Pacific Flyway

Imagine a living ribbon stretching from Alaska to Patagonia—this is the Pacific Flyway, a critical corridor for nearly a billion Pacific Birds each year. Migration timing varies, but coastal wetlands and bird habitats like California’s Central Valley are indispensable refueling stations.

Flyway conservation efforts safeguard these landscapes, ensuring migratory bird routes remain open. Without protected stopovers, the Pacific Americas Flyway’s delicate balance would unravel, threatening countless species.

| Key Species | Major Stopover Sites |

|---|---|

| Western Sandpiper | Fraser River Delta |

| Sandhill Crane | California’s Central Valley |

Central Flyway

Think of the Central Flyway as North America’s prairie expressway—a 5,000-mile corridor funneling nearly 400 bird species from Arctic tundra to Central America. You’ll find this longdistance migration route threading through ten U.S. states and six Canadian provinces, with bird migration routes converging dramatically at Nebraska’s Platte River each spring.

Flyway conservation and habitat restoration efforts protect critical wetlands where birds refuel during migration timing windows. Bird tracking data reveals striking migration patterns:

- Over 80% of North America’s Sandhill Cranes pass through Nebraska annually

- The Prairie Pothole Region breeds roughly 70% of continental mallards

- Climate adaptation strategies now guide management across 400 documented species using this flyway

Mississippi Flyway

Stretching 2,000 miles from central Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi Flyway channels over 325 bird species along the continent’s most trafficked migration corridor. You’ll witness approximately 15 million waterfowl—roughly 40% of North America’s total—traversing this route annually, with peak migration timing between late October and early December.

Stopover sites throughout the Lower Mississippi Valley host densities exceeding 200,000 birds per square mile, providing essential waterfowl habitat for Mallards, Gadwalls, and Snow Geese.

Flyway conservation programs coordinate bird population monitoring across this critical artery, where North American bird migration patterns converge with striking predictability along flyways following the Mississippi River Basin.

Atlantic Flyway

You’ll find the Atlantic Flyway arcing from Canada’s Arctic coast to the Caribbean, guiding more than 500 bird species across 3,000 miles of coastline. This migration route channels over one billion birds annually, with Species Diversity unequaled among North American flyways. Migration Timing peaks between March and May, when breeding urgency drives northward movement, while autumn patterns concentrate along coastal Bird Habitats from September through November.

- Over 800,000 shorebirds refuel at Chesapeake Bay during peak migration windows

- Red Knots traverse 10,000+ miles, stopping at Delaware Bay for horseshoe crab eggs

- Climate Impact threatens coastal wetlands, with 13% of monitored populations declining

- Flyway Conservation programs coordinate monitoring across 17 states and two Canadian provinces

East Atlantic Flyway connections extend protection priorities beyond continental boundaries, reinforcing international cooperation for bird migration patterns.

Navigation Methods Used

Birds navigate thousands of miles using a sophisticated toolkit of sensory abilities, each method refined through millennia of evolutionary pressure. Migratory species often combine multiple navigation strategies, switching between them as conditions change throughout their journey.

Let’s explore the four primary methods that guide birds across continents and oceans.

Celestial Navigation

When you watch migrating birds navigate by night sky, you’re witnessing a precision instrument honed over millennia. Approximately 90% of nocturnal migrants rely on star patterns and moon cues for astronomical orientation, calibrating their internal compass with accuracy rates exceeding 80% under clear conditions.

During daylight, solar navigation takes over—birds track the sun’s arc, compensating for its 15-degree hourly shift across the horizon. These bird navigation strategies integrate seamlessly with other avian navigation techniques, though cloud cover can reduce successful navigation by 17%, revealing how deeply migration patterns depend on celestial visibility for precise directional guidance.

Magnetic Orientation

You might be surprised to know that birds read the world’s magnetic fields as if tracing invisible lines across continents. Their magnetoreception relies on cryptochrome proteins in the retina, forming geomagnetic maps for precise compass navigation. When celestial orientation cues vanish, these avian navigation techniques shine brightest, guiding migration patterns through darkness and cloud.

- Magnetic Fields sensed via retinal cryptochrome

- Internal compass navigation system

- Geomagnetic maps for migration accuracy

- Orientation cues shift with environmental changes

Visual Landmarks

When you study how birds traverse, you’ll observe that visual signposts function as reliable navigation aids throughout their journeys along established flyways. These terrain features—from mountain ridges to coastlines—form geographic memories that guide migration patterns with striking precision.

Birds traversing over familiar terrain demonstrate return accuracy rates exceeding 70% in controlled release studies, confirming their dependence on signpost recognition for orientation. Visual cues become particularly vital during final approach stages, allowing you to witness birds pinpointing breeding sites within a kilometer range. Homing pigeons supplement compass navigation with landscape references, maintaining normal homing even when magnetic or celestial inputs are experimentally obscured.

Four critical visual elements support bird navigation strategies:

- Coastal boundaries – Shorelines provide unmistakable edges directing oceanic migrations

- River corridors – Winding waterways create natural pathways through complex terrain

- Mountain chains – Ridge systems serve as prominent directional guides across continents

- Forest transitions – Vegetation boundaries signal essential stopover locations for refueling

Sense of Smell

Beyond visual landmarks, you’ll find that birds construct olfactory maps using chemical cues from forests, oceans, and cities. These scent markers—pine monoterpenes, marine dimethyl sulfide—form odor gradients spanning over 100 kilometers, allowing birds to extract spatial information from atmospheric chemistry.

Experimental studies reveal that birds deprived of smell navigation fail homing attempts up to 80% of the time when released in unfamiliar territory. By associating specific aromas with wind direction over months, migratory bird habitats become encoded as invisible chemical landscapes.

This integration of smell with magnetic and celestial bird navigation strategies ensures successful journeys along established migration patterns, even when other avian navigation systems face disruption.

Migration Patterns Types

Birds don’t follow a single migration playbook—they’ve evolved distinct strategies shaped by distance, timing, and the unpredictability of their environments. Understanding these patterns reveals how species balance survival against the costs of travel.

Let’s look at the three main types that define how birds move across the globe.

Long Distance Migration

Long-distance migrants push the boundaries of avian endurance, traversing entire continents and oceans in journeys that span thousands of kilometers annually. These flyways demand exceptional physiological adaptations, with migration timing finely tuned to photoperiod cues and seasonal resource peaks. Climate impact increasingly disrupts these bird migration patterns, forcing shifts in stopover ecology and arrival synchrony. Bird tracking studies reveal that conservation efforts must prioritize corridor connectivity, as long-distance migration routes face mounting habitat fragmentation. You’ll witness nature’s most impressive navigation feats when you understand these epic movements.

- Arctic Terns complete nearly 90,000 km round trips between polar extremes, the longest migration routes documented

- Bar-tailed Godwits fly nonstop for roughly 6,800 km across the Pacific in single-leg crossings lasting six to seven days

- Blackpoll Warblers undertake 2,000-mile transatlantic flights, steering through open ocean despite their diminutive size

- Hudsonian Godwits now arrive six days later than a decade ago, reflecting climate-induced migration timing shifts

- Extensive datasets show 51% of tracked long-distance migrants complete their journeys successfully under current environmental pressures

Short Distance Migration

Short-distance migrants, such as American robins and dark-eyed juncos, travel less than 1,000 kilometers, wintering within temperate zones rather than crossing continents. These migration patterns closely follow local temperature shifts and food availability, with habitat quality dictating stopover choices along familiar flyways. Climate adaptation allows for flexible migration timing, as birds respond to warm spells instead of rigid photoperiod cues. Partial migration occurs when some individuals stay year-round while others move, demonstrating varied behavior within single populations.

| Migration Feature | Short-Distance Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Distance Covered | Generally under 1,000 km; some species migrate only 5 km locally |

| Timing Flexibility | Respond to weather and food rather than fixed day-length triggers |

| Survival Strategy | 64% annual return rate; compensate with higher reproductive output |

| Climate Response | Earlier arrivals in warm springs; some populations cease migrating entirely |

These migration routes demand less physiological endurance than long-distance journeys. However, short-distance migration faces rising threats from urbanization and habitat fragmentation across temperate overwintering zones.

Irregular Migration

Irregular migration defies seasonal predictability, driven by climate variability and food scarcity rather than photoperiod cues. When boreal forests experience cone crop failures, species like crossbills and pine siskins stage irruptive migrations, traveling up to 1,500 kilometers beyond normal ranges.

Nomadic behavior allows these facultative migrants to redirect mid-route, responding to ecological disruption through social cues and opportunistic foraging. Unlike altitudinal migration’s elevation shifts, irregular patterns create temporary abundance anomalies, with some populations expanding wintering areas by 800 kilometers during resource crashes.

Global Migration Routes

While North America’s flyways show how millions of birds navigate a single continent, you’ll find that migration is truly a global phenomenon. Birds cross oceans, deserts, and entire hemispheres along ancient pathways that connect breeding grounds in the far north to wintering sites thousands of miles away.

Here are the major flyways that guide migratory species across the Old World, Asia, Africa, and Australasia.

East Atlantic Flyway

The East Atlantic Flyway spans 36 countries, connecting Arctic breeding grounds to West African wintering sites for approximately 90 million birds annually. You’ll witness outstanding habitat preservation efforts supporting this bird migration corridor, where 42% of monitored populations show long-term increases despite climate impact challenges.

Migration routes depend on critical wetlands in Mauritania and Guinea, where millions of shorebirds refuel during their transcontinental journey. However, flyway ecology faces mounting pressures from fishing disturbances, tourism expansion, and agricultural encroachment, making bird conservation increasingly essential for maintaining migration patterns along this Atlantic flyway network.

Black Sea Mediterranean Flyway

You’ll find the Black Sea Mediterranean Flyway supporting an estimated 2.5 billion migratory birds passing through the Levant twice annually. However, population trends for wetland birds declined 65% over a decade.

Bird tracking reveals critical stopover sites—the Bosporus, Sudd wetlands, Jezreel Valley—where species diversity includes recovering Dalmatian pelican populations that increased from 1,730 pairs to 2,437 pairs between 2000 and 2012.

However, habitat conservation remains urgent as 2.6 million birds face illegal hunting in Lebanon alone, threatening migration timing across Eurasian flyways and disrupting flyway ecology throughout these essential bird migration routes and migration patterns.

East Asia East Africa Flyway

Spanning 56.7 million square kilometers across 64 countries, this avian flyway creates a living bridge between Eastern Siberia and South Africa, supporting 331 species through journeys that test the limits of endurance. You’ll discover migration routes where bird tracking reveals the Amur falcon’s remarkable 22,000-kilometer roundtrip—crossing the Indian Ocean with precision that climate impact increasingly threatens. Migration timing along these bird migration patterns depends on seven major sites hosting over one million birds each during peak periods, while habitat preservation efforts protect critical stopover locations where flyway conservation meets urgent necessity.

- Spring returns compress into six weeks of coastal navigation along East Africa

- Willow warblers comprise 15.8% of all passerines using these avian flyways

- Indian Ocean crossings demand physiological adaptations found nowhere else

- East AsiaEast Africa Flyway connectivity spans three continents of ecological interdependence

Central South Asian Flyway

Stretching across 30 countries from northern Siberia to tropical Asia, the Central South Asian Flyway acts as a critical migration corridor for at least 279 waterbird populations representing 182 species. You’ll witness flyway ecology supporting critically endangered species like the northern bald ibis and white-bellied heron, while India alone provides wintering habitat for 257 waterbird species. However, these migration routes face severe threats from hunting, habitat degradation, and unsustainable water management that endanger bird population stability across the Central South Asian Flyway.

| Flyway Characteristic | Key Data |

|---|---|

| Geographic Coverage | 30 countries across West and South Asia |

| Waterbird Species Diversity | 182 species (279 populations) |

| India’s Role | 257 waterbird species; 9 critically/endangered |

| Russia’s Contribution | 143 migratory species supported |

| Conservation Threats | Hunting, habitat loss, water mismanagement |

Bird migration patterns here demand urgent habitat conservation efforts to protect the flyway’s irreplaceable ecological connectivity.

East Asian Australasian Flyway

From Russia and Alaska down to Australia and New Zealand, the East Asian-Australasian Flyway creates an extraordinary migration corridor supporting over 50 million waterbirds annually. You’ll find this flyway connecting 24 countries through critical wetland networks, with species monitoring documenting 32 globally threatened species dependent on these migration routes. Habitat preservation efforts now protect 1,060 internationally important sites where migratory birds refuel during their journeys.

Consider these flyway conservation priorities:

- Lake Teshekpuk hosts over 40% of Alaska’s North Slope aquatic birds despite covering just 18% of the reserve area

- Migration ecology research utilizes 491,730 bird count records from 3,212 sites across the East Asian-Australasian Flyway

- Bird tracking reveals 250+ distinct waterbird populations traversing these migration routes seasonally

- Species monitoring identifies 19 near-threatened species requiring immediate protection throughout the flyway

Bird migration patterns here demand coordinated international action to maintain ecological connectivity across this vast network.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the major migration routes for birds?

Before compasses charted the seas, birds mastered their own aerial highways across continents. You’ll discover four major North American flyways—Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic—that channel millions of migrating birds between breeding grounds and wintering habitats each year, forming critical corridors for species protection and habitat preservation along these ancient migration routes.

What are the 8 major migratory bird flyways?

Eight major flyways form the backbone of avian geography worldwide: Pacific Americas, Central Americas, Atlantic Americas, East Atlantic, Black Sea–Mediterranean, East Asia–East Africa, Central Asian, and East Asian–Australasian.

These migration routes connect breeding and wintering grounds across continents, supporting billions of migratory birds annually and shaping migration ecology and wildlife preservation efforts globally.

What are the four flyways?

You might assume each flyway operates independently, but these migration routes actually overlap and merge at key junctures.

North America’s four major flyways—Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific—guide over a billion birds annually between Arctic breeding grounds and southern wintering habitats, with the Central and Mississippi Flyways converging near the Gulf of Mexico.

What is the word for a bird migration route?

The standard terminology for bird migration routes includes “flyway,” which describes the broad corridor migratory species follow between breeding and wintering grounds, and “migratory pathway,” referring to the specific route individual birds or populations use during their seasonal journeys across continents.

How do birds know when to start migrating?

Photoperiod cues provide powerful prompts, triggering internal biological clocks that respond to changing daylight patterns.

Hormonal changes, genetic factors, and environmental cues like temperature shifts work together, creating nature’s precise timing system for epic migratory journeys.

What happens when migration routes get blocked?

When migration routes encounter barrier effects or route obstruction, you’ll witness birds attempt detours, exhaust energy reserves crossing hazardous terrain, or become disoriented—leading to mortality rates exceeding 20 times normal levels during blocked passages through ecological barriers.

Do young birds learn migration from parents?

Like hatchlings reading an ancient map, young birds rely on genetic predisposition and innate navigation for their inaugural journeys. While most species—around 95%—migrate independently using inherited instincts, social learning enhances accuracy by 38% through flock dynamics and parental guidance in select species.

How does climate change affect migration timing?

Rising temperatures disrupt migration timing, with many species arriving roughly 22 days earlier per decade in spring and departing later in fall. Climate shifts create phenological mismatches between birds and their food sources, as insect emergence responds more sensitively to temperature than migration timing does.

Adaptive responses vary by species.

Why do some birds migrate at night?

You’ll discover that cooler nighttime air helps birds conserve precious energy through thermoregulation, while darkness shields nocturnal migrants from diurnal predators like raptors—cutting predation risk by 50-70% and creating calmer atmospheric conditions perfect for long-distance flight.

How do birds choose which route to take?

You navigate by blending genetic instinct with learned experience—your internal compass guides first journeys, while environmental cues like stars, magnetic fields, and social learning from older birds enhance route optimization over time.

Conclusion

Every bird on Earth navigates an invisible atlas etched across skies, oceans, and mountain ranges—a network so intricate that even a single species might rely on star charts, magnetic fields, and ancestral memory simultaneously.

By understanding the types of bird migration routes, you gain insight into flyways that connect hemispheres, patterns shaped by distance and terrain, and navigation methods refined across millennia.

These routes aren’t static lines but living corridors that adapt, shift, and endure—proof that freedom, for birds, is never aimless but profoundly intentional.