This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

You don’t need binoculars to spot brown and black birds—they’re perched on your fence, hopping through your garden, and probably raiding your feeders right now. These feathered neighbors wear earthy tones that blend into bark and soil, yet each species tells a distinct story through its plumage patterns, beak shape, and behavior.

A glossy black body paired with a chocolate-brown head signals a Brown-headed Cowbird, while rusty sides and a bold black hood mark the Eastern Towhee scratching through your leaf litter. Understanding these field marks transforms casual backyard watching into confident identification.

Whether you’re tracking a Harris’s Sparrow’s pink bill or an Orchard Oriole’s chestnut vest, knowing what to look for turns mystery birds into familiar faces you’ll recognize season after season.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Common Brown and Black Bird Species

- Identifying Brown and Black Birds

- Habitats and Geographic Distribution

- Behavior and Diet of Brown and Black Birds

- Conservation and Population Trends

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What are some examples of brown-headed birds?

- How can I attract brown and black birds to my backyard?

- How do brown and black birds behave?

- What do brown and black birds eat?

- Where can I find brown and black birds?

- How do brown and black birds attract mates?

- What predators commonly threaten brown and black birds?

- How long do brown and black birds live?

- Can brown and black birds hybridize with each other?

- Do brown and black birds migrate at night?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Brown and black birds like cowbirds, towhees, and grosbeaks share earthy color palettes but reveal distinct identities through specific field marks—chocolate heads against glossy bodies, rusty sides with black hoods, or pink bills with bold bibs—that transform casual backyard glances into confident species identification.

- Behavioral strategies separate these species dramatically, from the brown-headed cowbird’s controversial brood parasitism (exploiting over 200 host species with 25% parasitism rates in dense woodlands) to the eastern towhee’s signature double-kick foraging and the orchard oriole’s seasonal shift from insect-hunting to fruit-eating.

- Habitat fragmentation and climate change threaten several species severely—Harris’s sparrows dropped 18% over three decades while orchard orioles fell 8–15% in urban edges—though conservation efforts using native plantings and habitat restoration have boosted brown and black bird abundance by 10–25% in restored areas.

- These birds occupy wildly different ecological niches across North America, from cactus wrens thriving in southwestern desert landscapes and brown-capped rosy-finches adapting to high-altitude alpine zones to northern bobwhites facing conservation challenges in declining grassland habitats.

Common Brown and Black Bird Species

If you’re stepping outside with binoculars in hand, you’ll want to know which brown and black birds might cross your path. These species blend earth tones with darker plumage in striking combinations, making them both beautiful and surprisingly tricky to identify.

Let’s break down nine common birds that wear this distinctive color palette, from backyard regulars to high-altitude specialists.

Brown-headed Cowbird

The brownheaded cowbird masters a controversial survival strategy you won’t find in most bird behavior guides. This smallish songbird sports a chocolate-brown head contrasting with an iridescent black body, making brownheaded cowbird identification straightforward once you know the pattern.

What sets this species apart in brown and black birds:

- Brood parasitism behavior – Females lay eggs in other birds’ nests, with at least 80% of urbanized nest locations showing this parasitic nesting habit

- Feather patterns – Males display glossy black plumage while females wear subdued brown tones

- Migration routes and song variations – Found across diverse habitats from woodlands to backyards, adapting their calls regionally

Understanding the bird’s behavior requires analyzing its universal life themes to grasp its survival strategies.

Black-headed Grosbeak

While cowbirds exploit others’ nests, the blackheaded grosbeak builds its own in western North America’s deciduous woodlands. Males flash a striking black head against an orange-yellow chest—bold bird species identification markers you can’t miss. Their nesting sites favor oak and willow canopies, where breeding habits peak from May through August.

Listen for melodious song variations that define their feeding behavior territories, blending insect-hunting with seed-cracking prowess in classic avian biology fashion. The blackheaded grosbeak’s behavior also illustrates the importance of themes in understanding animal social structures.

Orchard Oriole

Smaller than grosbeaks, male Orchard Orioles wear rusty chestnut and jet-black plumage—your ticket to quick bird species identification in orchards and open woods. You’ll spot them during breeding season patterns from late spring through summer across eastern North American birds territories.

Their fruit eating behavior and insect-gleaning define oriole nesting habits, while orchard oriole migration sweeps them to Central America each fall.

Listen for sharp chatters revealing oriole social structure in deciduous canopies perfect for bird watching.

Eastern and Spotted Towhee

You’ll recognize Eastern Towhees by their black head and upperparts set against rusty-brown sides—think tuxedo meets autumn leaves. Spotted Towhees mirror this pattern but flash white wing dots across western territories.

Both species showcase bird song patterns through distinctive “drink-your-tea” calls while executing their signature double-kick foraging strategies through leaf litter.

Towhee migration varies: Eastern birds hold year-round territories while Spotted cousins shift seasonally, making brown and black birds identification easier when you track regional presence and feather coloration against nesting habits in woodland edges.

Harris’s Sparrow

Watch for the bold black bib and pink bill—that’s your Harris’s Sparrow signaling across Great Plains wintering grounds. These chunky sparrows breed in Canada’s boreal forests, then funnel south through specific migration corridors, making sparrow migration tracking a conservation priority.

Their mottled brown backs contrast sharply with that striking facial pattern, cementing their place in brown and black birds identification and ornithology field studies.

Cactus Wren

A striking white eyebrow stripe and long, downturned bill mark the Cactus Wren as master of desert adaptation. You’ll find this year-round resident thriving in southwestern U.S. cactus landscapes, building bulky nests in cholla and mesquite.

Their distinctive song patterns—harsh, repetitive chatters—echo across arid scrub, making bird identification straightforward even when the bird’s tucked deep in desert vegetation.

Brown-capped Rosy-Finch

High-altitude mountainous environments shape the Brown-capped Rosy-Finch’s existence. You’ll spot males displaying rosy-pink underparts contrasting with their brown crown and back. These hardy bird species adapt to rocky alpine zones in the western United States, where extreme habitat adaptation defines their breeding patterns.

Black wings flash against snow as they forage, making bird identification easier. Feather molting shifts their appearance seasonally, showcasing striking avian characteristics in these black and brown birds.

Northern Bobwhite

Picture a plump, ground-dwelling quail inhabiting eastern shrublands—that’s the Northern Bobwhite. Males sport tan and brown feather patterns with a distinctive dark throat patch, while females show subtler brown facial coloring. These black birds with brown heads face declining conservation status due to habitat loss.

- Nesting habits favor dense grassland cover

- Quail migration patterns remain mostly sedentary

- Habitat restoration efforts target agricultural edges

- Brown thrasher coexists in similar territories

California Quail

You’ll recognize California Quail by their rounded bodies and that iconic forward-curving black plume perched like a tiny flag. Males display gray and brown feather patterns with scaly backs, thriving in California’s chaparral and oak woodland quail habitat.

Their distinctive “chi-ca-go” call echoes through scrublands. While not true migrants, quail behavior includes seasonal elevation shifts. Wildlife conservation efforts protect these sedentary birds from suburban sprawl threatening their natural range.

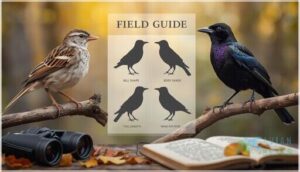

Identifying Brown and Black Birds

You can’t identify a bird by guessing—you need to know what to look for in the field. The combination of color, shape, and key markings will lead you to the right species faster than any single trait alone.

Let’s break down the most reliable field marks that separate brown and black birds from one another.

Plumage Color and Patterns

When you’re scanning for black birds with brown heads or full brown plumage, understanding feather pigmentation and iridescence makes all the difference. Spectral reflectance and molt patterns shift colors by 5–8% seasonally—here’s what to watch for:

- Brown-headed Cowbirds show glossy brown with subtle sheen variations

- Color morphs appear in Towhees, from slate-black to brownish tones

- Grosbeaks display intense yellows against bold black

- Regional differences affect Brown Thrasher and similar species’ brightness

Size, Shape, and Beak Features

Beyond color, you’ll want to focus on body proportions and beak morphology for accurate bird identification.

Brown-headed Cowbirds measure 18–22 cm with short, stout bills for seed-cracking, while Black-headed Grosbeaks sport thick beaks ideal for crushing. Eastern Towhees show chunky builds with heavy, conical bills, and Harris’s Sparrows display compact frames.

Understanding these structural differences unlocks avian diversity in black birds with brown heads.

Distinctive Markings and Field Marks

Once you’ve noted size and shape, zero in on facial patterns and wing bars—they’re your field marks for certain identification.

Brown-headed Cowbirds show pale secondaries contrasting with dark wings, creating subtle wing bars about 6–8 mm wide. Black-headed Grosbeaks flash bold white eye rings, while towhees reveal distinctive throat patches.

These head markings and tail feathers separate similar black birds with brown heads, unlocking true avian diversity.

Habitats and Geographic Distribution

Understanding where these brown and black birds live helps you know where to look—and when you’re most likely to spot them. Their habitats range from deep forests and open grasslands to your own backyard, depending on the species and time of year.

Let’s explore the environments these birds call home and how their presence shifts with the seasons.

Forests, Grasslands, and Deserts

You’ll find these species across wildly different terrain—each habitat shaped by its own fierce ecology. Forest ecology sustains grosbeaks and Common Grackles in mixed woodlands, while grassland fires maintain open spaces where Northern Bobwhite thrive. Desert landscapes host the resilient Cactus Wren among cacti.

Ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation depend on protecting these habitats, where brownheaded cowbirds and other blackbirds navigate their complex survival strategies.

Urban and Suburban Environments

Many brown and black birds have claimed city ecosystems as their own territory. Urban planning that prioritizes green spaces and bird-friendly designs sustains up to 60–80% of regional populations—suburban wildlife thrives when neighborhoods blend native plantings with open corridors.

Brown-headed cowbirds and blackbirds exploit backyard bird feeders, transforming urban bird habitats into unexpected strongholds where behavior adjusts to human-dominated landscapes.

Regional and Seasonal Presence

Migration patterns shape where you’ll spot these birds throughout the year. Brown-headed Cowbirds shift south from March through August, peaking in late April when nest parasitism intensifies across regional habitats. Black-headed Grosbeaks arrive in western mountain forests from February to May, while Harris’s Sparrows undertake impressive journeys between Arctic breeding grounds and southern winter ranges.

Climate effects and seasonal shifts continuously reshape habitat preferences and regional distribution across North America.

Behavior and Diet of Brown and Black Birds

You can learn a lot about a bird just by watching how it moves and what it eats. Brown and black birds have developed fascinating strategies to find food, communicate with each other, and survive in their environments.

Let’s look at the key behaviors that set these species apart.

Foraging Techniques and Diet Preferences

You’ll notice impressive dietary adaptations across brown and black species—Eastern Towhees kick backward through leaf litter, while Orchard Orioles hunt insects that supply up to 70% of their breeding-season energy.

Seed selection matters: Harris’s Sparrows shift from seeds to fruits by December, increasing fruit intake to 40%. Ground foragers show 12–18% higher seed consumption in leaf litter than canopy feeders.

Vocalizations and Songs

You’ll discover that song patterns reveal survival strategies—Brown-headed Cowbirds produce 8–12 distinct calls, often mimicking host species as part of their brood parasitic behavior, while Black-headed Grosbeaks offer rich six-note melodies that shift with geography.

- Eastern Towhees deliver their iconic “drink-your-tea” sequence followed by a descending trill

- Orchard Orioles blend flute-like warbles with sharp buzzy notes during territorial disputes

- Dawn chorus intensifies vocal learning, with males extending trill duration by 15–25% during breeding season

Unique Behavioral Traits (e.g., Brood Parasitism)

Brood parasitism rewrites the rules of bird behavior. You’ll see Brown-headed Cowbirds laying eggs in host nests, where their chicks hatch early and evict hosts in 60% of cases.

This nest parasite strategy exploits over 200 host species across North America. Watch for parasitism rates climbing to 25% in interior woodlands, where higher host nest density fuels this cunning nesting strategy.

Brown-headed Cowbirds exploit over 200 host species across North America, with parasitism rates reaching 25% in dense woodlands

Conservation and Population Trends

The fate of these striking brown and black birds isn’t written in stone—some species are holding steady while others face an uphill battle.

Understanding what’s threatening their survival and where populations stand gives you the full picture of their conservation status.

Let’s look at the key challenges these birds face, how their numbers are shifting, and what’s being done to protect them.

Threats to Brown and Black Bird Species

You’ll find that threats facing brown and black birds often stem from habitat fragmentation—42% of brown-headed cowbird habitat has vanished since 1990 due to agriculture and urban sprawl.

Consider these critical pressures:

- Climate shifts advancing nesting by 3–6 days per decade, creating food mismatches

- Nest parasitism by brownheaded cowbirds reducing host survival 15–25%

- Lead poisoning and pesticides cutting nest success 6–9%

- Human disturbance through light, noise, and collisions

Wildlife conservation efforts and informed conservation decisions depend on understanding these intersecting challenges to protect bird species diversity.

Population Stability and Decline

Population trends reveal stark contrasts—Eastern Towhees held steady from 2010 to 2020, while Harris’s Sparrows dropped 18% over three decades due to habitat fragmentation and drought. Black-headed Grosbeaks show population stability with 0.3% annual growth, but Orchard Orioles fell 8–15% in urban edges.

Climate change and brownheaded cowbird parasitism complicate wildlife conservation efforts, demanding adaptive conservation strategies and informed conservation decisions for declining bird species.

Conservation Efforts and Habitat Protection

You can join the fight for these birds through wildlife conservation and habitat protection.

Species preservation programs now safeguard 40% more land under federal frameworks, while habitat restoration in grasslands boosts juvenile survival by 12–27%.

Nature conservation easements connect fragmented oak woodlands, and ecosystem management with native plantings increases biodiversity protection, raising brown and black bird abundance by 10–25% in restored areas.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are some examples of brown-headed birds?

Scanning the treetops, you’ll spot the Brownheaded Cowbird’s chocolate crown and the Browncapped RosyFinch’s cinnamon cap.

Northern Flicker, Fox Sparrow, and Darkeyed Junco also showcase distinctive brown head colors and varied beak shapes.

How can I attract brown and black birds to my backyard?

Start with sunflower seeds and native plants to draw feeder birds in. Add water features at multiple heights for backyard birding success.

Your backyard layout determines which Brown-headed Cowbird behavior and bird behavior and habitat patterns you’ll observe.

How do brown and black birds behave?

During breeding season, insect consumption jumps to 40–60% of the diet for many brownish passerines. You’ll notice territorial defense, flocking patterns, and foraging strategies vary widely—from the brown-headed cowbird’s brood parasitism to towhees’ ground-scratching techniques.

What do brown and black birds eat?

You’ll find most of these species switching between seeds, insects, and fruit depending on the season. Cowbirds lean heavily on seeds and grains, while grosbeaks and orioles chase caterpillars during breeding, then pivot to berries and nectar.

Where can I find brown and black birds?

You’ll spot these species in diverse settings—from wetland habitats and bird sanctuaries to urban landscapes and backyard feeders.

Migration patterns shift their presence seasonally, making timing essential for observing Brownheaded Cowbirds, Common Grackles, and others.

How do brown and black birds attract mates?

In matters of love, actions speak louder than words. Male birds attract mates through bold plumage, complex song patterns, and territorial displays—traits that signal fitness, resource access, and parenting potential during breeding season.

What predators commonly threaten brown and black birds?

Raptor predation from hawks—like the Northern Harrier—poses serious risks, while feral cat threat and nest parasites such as cowbirds compound dangers.

Avian brood losses also stem from raccoons and corvids raiding predator habitat zones near woodland edges.

How long do brown and black birds live?

Most species with brown or black plumage live two to seven years in the wild. Survival strategies and mortality rates vary considerably.

Brown-headed Cowbirds average 5–3 years, while Black-headed Grosbeaks reach 4–6 years.

Can brown and black birds hybridize with each other?

Hybridization between distinctly colored species remains exceedingly rare. Genetic barriers and reproductive isolation prevent most interbreeding, though closely related blackbird species occasionally produce hybrids.

Mate choice relies on song and behavior, not plumage alone.

Do brown and black birds migrate at night?

Many brown and black bird species migrate at night, with nocturnal flights accounting for 15-25% of migratory movements. Radar tracking and acoustic monitoring reveal peak activity during autumn corridors and new moon phases.

Conclusion

For all their camouflage, brown and black birds don’t exactly hide—they announce themselves through cowbird chatter, towhee scratches, and grosbeak melodies that cut through morning air.

You’ve learned the field marks that separate one earth-toned species from another, turning what once looked like “just another brown bird” into a roster of distinct neighbors with names, habits, and stories.

Your binoculars aren’t optional anymore; they’re how you read the landscape’s most overlooked characters.