This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

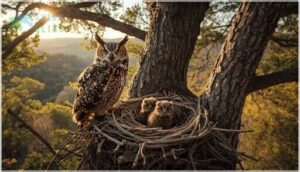

While most birds are still planning their spring families, Great Horned Owls are already deep into parenting mode—laying eggs as early as January when snow still blankets the ground. This isn’t reckless timing but a calculated strategy refined over millennia, giving their young a vital head start when prey becomes abundant in spring.

These formidable raptors don’t bother building their own nests, preferring to commandeer abandoned hawk or heron structures high in mature trees. Understanding great horned owl nesting behavior reveals how these adaptable predators balance harsh winter conditions, territory defense, and the demanding work of raising owlets that won’t leave home for months.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Great Horned Owl Nesting Season

- Preferred Nesting Sites

- Nest Construction and Materials

- Egg Laying and Incubation

- Raising and Fledging Owlets

- Nesting Success and Conservation

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What time of year do Great Horned Owls nest?

- Where does a Great Horned Owl nest?

- Where do Great Horned Owls prefer to nest?

- Do owls nest in the same place every night?

- When do great horned owls lay eggs?

- How long is the fledgling period?

- What materials line the nest?

- How many eggs are typically in a clutch?

- What is the incubation period for eggs?

- When do great horned owls lay their eggs?

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- Great Horned Owls nest in winter—courting in December-January and laying eggs in February-March—so their owlets can master flight exactly when spring floods the landscape with inexperienced prey, turning harsh timing into a competitive advantage.

- These raptors don’t build nests but repurpose abandoned hawk, eagle, and heron platforms in tall trees 15-60 feet high, selecting sites based on branch strength, forest density for concealment, and proximity to open hunting areas.

- The female incubates 2-3 eggs for 28-35 days through freezing temperatures (tolerating drops to -35°F) while the male hunts continuously, with owlets fledging at 28-36 days but remaining dependent on parents for 3-6 months until they establish their own territories.

- Nest success depends on minimal human disturbance, habitat quality, and prey availability—you can support nesting owls by preserving mature trees with cavities, installing nest boxes 15+ feet high, avoiding anticoagulant rodenticides, and reducing light pollution near nesting sites.

Great Horned Owl Nesting Season

Great Horned Owls don’t wait for spring’s warmth to start their families—they’re already hard at work when most birds are still hunkered down against winter’s chill. This early nesting season might seem counterintuitive, but these powerful raptors have evolved to thrive in conditions that would challenge other species.

Their hunting prowess means Great Horned Owls can secure the rabbits and rodents described in owls in Alabama even when snow blankets the ground.

Great Horned Owls raise their families in winter’s coldest months, thriving when other birds won’t even nest

Let’s look at when these owls begin nesting, why they choose such harsh conditions, and what environmental factors shape their breeding timeline.

Typical Nesting Months and Timing

Usually, you’ll find great horned owl nesting season kicks off surprisingly early—pair bonding and courtship begin in December through February in most of North America.

Eggs are usually laid in February or March in temperate zones, with incubation lasting 28 to 35 days. Owlets hatch about three to four weeks after the first egg, and fledging times arrive around six to ten weeks later, completing these outstanding breeding cycles.

Nesting activities in birds often coincide with seasonal environmental changes that signal the best time for reproduction.

Why Owls Nest in Winter

Nesting in winter might seem odd, but great horned owls exploit prey availability that peaks in late winter and early spring—exactly when their hatchlings need it most.

Cold weather drives them to claim nesting sites early, defending territory during scarce food periods. Short daylight hours also concentrate hunting activity, making incubation and feeding routines more predictable and efficient for these exceptional winter-adapted raptors.

Their early nesting is highlighted by territorial defense and distinctive calls, as detailed in these owl nesting behaviors and adaptations.

Environmental Factors Influencing Nesting

Beyond cold tolerance, you’ll find that weather patterns, nesting microclimates, and ecosystem balance all shape when and where great horned owls settle down.

Climate change shifts prey cycles, while habitat fragmentation limits suitable sites. Environmental factors and nesting success intertwine—canopy cover moderates temperature, wind exposure affects incubation, and prey abundance hinges on ecological adaptation across changing landscapes, illustrating core principles of wildlife ecology and conservation in environmental science.

Preferred Nesting Sites

Great Horned Owls don’t build their own nests from scratch—they’re opportunists who claim real estate that’s already built.

You’ll find them settling into elevated spots with good views and plenty of cover, from tall trees to rocky outcrops. Here’s where these resourceful raptors usually set up their winter nurseries.

Common Tree and Perch Selections

Great horned owls scan the landscape for tall, mature trees—especially oaks and pines—with strong limbs that offer both stability and a commanding view. You’ll find their nesting sites tucked 15 to 60 feet high, where they can monitor hunting zones while staying safe from ground threats.

Three factors drive their perch selection:

Male owls often choose elevated perches that amplify their hooting calls during courtship, a behavior detailed in why owls hoot and what their calls mean.

- Branch strength to support heavy adults during incubation

- Forest density that balances concealment with visibility

- Proximity to open areas like meadows for efficient hunting

Use of Abandoned Raptor and Heron Nests

Instead of constructing their own platforms, great horned owls claim abandoned nests from hawks, eagles, and great blue herons—ready-made infrastructure that saves energy during the owl nesting season.

You’ll spot nest reuse benefits in mature cottonwoods and oaks along rivers, where raptor nest adaptation gives owls immediate access to sturdy platforms 20 to 60 feet high, complete with strong crotches that support incubating adults.

Adaptation to Urban and Suburban Areas

Across cities and towns, great horned owl breeding patterns now thrive in urban habitat use zones where mature trees and green corridors mimic wild landscapes.

You’ll find suburban nesting in:

- Tall park trees with abandoned crow or hawk platforms

- Building ledges and protected crevices near city prey base concentrations

- Nesting boxes installed through urban planning strategies that reduce human owl conflict

Urban wildlife management and wildlife habitat creation efforts help pairs raise young successfully amid development.

Nest Construction and Materials

Great Horned Owls aren’t builders—they’re more like savvy investors who know a good deal when they see one. Rather than constructing nests from scratch, these resourceful raptors repurpose structures left behind by other birds, settle into natural tree hollows, or even adapt to human-made platforms.

Let’s look at how they transform these ready-made spaces into secure homes for their young.

How Owls Repurpose Existing Nests

When you watch a Great Horned Owl claim an old hawk or heron platform, you’re seeing nature’s supreme recycler in action. These birds don’t waste energy building from scratch—they adopt abandoned raptor nests, cliff ledges, and even barn lofts.

Here’s how repurposing strategies work:

| Nest Type | Selection Advantage | Typical Modification |

|---|---|---|

| Raptor platforms | Proven stability and prey access | Minor reinforcement with sticks |

| Tree cavities | Weather protection and concealment | Adjusted perch height for visibility |

| Urban structures | Reduced territorial conflict | Added insulating debris layers |

This nest reuse benefits breeding success—familiar sites mean earlier egg-laying and better predator defense. Site selection focuses on elevation, shelter, and food availability, allowing owls to concentrate on raising young rather than construction. Ecological adaptations like these explain why Great Horned Owl nesting habits thrive across diverse landscapes, from wilderness forests to suburban nest boxes.

Materials Used for Lining Nests

Once an owl claims a nest box or abandoned platform, you’ll notice the lining transforms into a quilted sanctuary. Fine plant materials—leaves, moss, lichens, and reeds—form water repellents and nest insulation, while feathers and fur add nest cushioning.

This nesting behavior creates a soft, warm microclimate that protects eggs from harsh temperatures, showcasing how owl nesting habits refine every detail at nesting sites.

Tree Cavities, Ledges, and Man-made Options

When natural tree hollows aren’t available, great horned owls turn to creative alternatives. Cavity selection favors mature trunks with openings 5 to 8 centimeters wide, while ledge design matters on cliff faces and building perches.

Urban nesting thrives when you install a nest box 4 to 10 meters high—proper nesting box placement mimics tree habitat and expands nesting sites across transformed landscapes.

Egg Laying and Incubation

Once a Great Horned Owl pair claims their nest site, the female begins laying eggs—usually 2 to 3 of them, spaced a few days apart.

What happens next is noteworthy: she’ll incubate those eggs through freezing temperatures while her mate stands guard and brings food. Here’s how egg laying and incubation unfold during these pivotal early weeks.

Number of Eggs and Laying Intervals

When you’re watching great horned owls during nesting season, you’ll usually find a clutch of two to four eggs at their nesting sites. The laying patterns follow a predictable rhythm that shapes the entire breeding cycle.

- Egg clutch size averages three eggs, though food-rich areas can support four

- Laying intervals space eggs 2-3 days apart, stretching over 4-11 days total

- Nesting cycles begin once the final egg arrives, synchronizing owlets’ hatching

Incubation Roles and Temperature Challenges

Once those eggs arrive, the female settles in for 30 to 37 days of nearly constant incubation period while temperatures plunge to -35°F around her.

Her body maintains the nest microclimate and fosters proper egg development even when she briefly steps away—eggs can handle -25°F for up to 20 minutes.

Meanwhile, the male hunts and delivers food, dividing parental roles that define great horned owl nesting season success.

Parental Defense During Incubation

During incubation, both parents act as nest guardians, intensifying their threat response when danger looms. You’ll notice defense strategies shift with predator proximity:

- Sharp alarm calls alert the mate to disturbances

- Upright postures and wing displays make adults appear larger

- Dive attacks physically deter nest invaders

- Silent exchanges occur when threats are distant

- Nocturnal vigilance peaks during high-risk hours

These incubation tactics guarantee great horned owl nesting season success through coordinated predator deterrence.

Raising and Fledging Owlets

Once the eggs hatch, both parents shift into high gear—the female broods the vulnerable owlets while the male hunts around the clock to keep everyone fed.

You’ll see dramatic changes in these young birds over just a few weeks, from helpless hatchlings to feisty fledglings ready to leave the nest. Here’s what happens during this critical growth period.

Feeding and Parental Care Routines

You’ll notice feeding strategies shift as nestlings grow—parents deliver prey every 1.5 to 2.5 hours at first, tearing food into manageable pieces to support rapid nestling development.

The female oversees brooding techniques while the male hunts, strengthening parental bonds through this division of labor. Their food delivery peaks at dawn and dusk, showcasing notable owl behavior and habitat adaptation that defines raptor behavior and animal parenting.

Growth Milestones and Development Stages

Within days of breaking through their shells, owlet development accelerates—eyes open by 7 to 10 days, sharpening sensory maturation for hunting awareness.

Feather growth begins around two weeks, while motor skills strengthen as juveniles practice wing beats near the nest. You’ll see parental guidance intensify during these stages, with adults coaching balance, coordination, and early prey-catching attempts that define great horned owl breeding patterns.

Fledging Timeline and Independence

Usually, fledging occurs between 28 and 36 days after hatching, though flight training extends well beyond that initial departure. You’ll observe three critical independence phase milestones:

- 28-36 days: Owlets leave the nest but remain nearby, dependent on parents

- 45-70 days: Primary feathers enable functional flight and hunting practice

- 3-6 months: Juveniles disperse to establish their own territories

Parental guidance shapes this entire juvenile development arc during great horned owl nesting season.

Nesting Success and Conservation

Not every Great Horned Owl nest makes it to fledging—nest success depends on habitat quality, prey availability, and how much disturbance the parents face from people or pets.

The good news is that these owls are remarkably adaptable, and in most of North America, their populations remain stable thanks to their flexible diet and nesting habits. Here’s what influences their breeding success and how you can help protect nesting owls in your area.

Factors Affecting Nest Survival

Nest survival hinges on several ecological challenges you mightn’t expect. Predation pressure from mammals and birds targets eggs and nestlings, particularly when nest concealment is poor.

Weather extremes—heavy rain, wind, or prolonged cold—can destroy nests or delay incubation. Food scarcity forces longer foraging trips, leaving nests vulnerable.

Habitat fragmentation disrupts hunting efficiency, while well-placed nest boxes can buffer some risks during the nesting season.

Human Impact and Habitat Disturbance

Your presence—and the way you shape landscapes—profoundly influences nesting success. Habitat fragmentation from development pushes foraging areas farther from nests, raising energy costs during critical breeding windows. Urban noise disrupts hunting and reduces vocalization rates, while light pollution shifts nocturnal hunting patterns. Human disturbance near nesting habitat increases stress, shortening incubation or triggering abandonment.

Consider these stark realities of human impact on wildlife habitat:

- Road traffic near nests increases shock risk to owlets and can drive parents away permanently

- Domestic pets prowling suburban yards heighten predation threats during vulnerable fledging stages

- Climate change desynchronizes prey peaks with nesting cycles, leaving owlets facing longer fasting periods

Wildlife conservation starts with understanding how your daily choices ripple through nesting habitat and beyond.

Conservation Tips for Supporting Nesting Owls

You can turn your property into a haven for nesting owls through habitat preservation and thoughtful design. Wildlife conservation begins at home—owl-friendly landscaping with native trees, strategic nest box installation at least 15 feet high, and avoiding anticoagulant rodent control methods all support bird conservation.

Wildlife-friendly lighting, shielded and motion-activated, protects nocturnal hunting routines while your nesting box provides critical shelter where natural cavities are scarce.

| Conservation Action | Key Practice | Owl Conservation Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Protect Mature Trees | Leave older trees with cavities standing; avoid pruning February–August | Preserves natural nesting sites and roosting spots |

| Install Nesting Boxes | Mount boxes 15+ feet high, spaced 100 yards apart | Provides safe alternatives when snags are limited |

| Safe Pest Management | Use snap traps or sanitation instead of anticoagulant poisons | Prevents secondary poisoning of hunting adults |

| Reduce Light Pollution | Install downward-facing, motion-activated fixtures near nest sites | Maintains natural hunting patterns and reduces stress |

| Manage Yards Naturally | Keep brush piles, rough grass patches, and limit pesticides | Boosts prey populations and hunting success |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What time of year do Great Horned Owls nest?

While most birds wait for spring’s warmth, Great Horned Owls begin their nesting season in late winter—courting in December and January, then laying eggs between February and March across their range.

Where does a Great Horned Owl nest?

You’ll find these powerful raptors claiming abandoned hawk nests, eagle platforms, and Great Blue Heron structures in tall trees.

They also favor cliff ledges, rocky outcrops, tree cavities, and even urban rooftops when natural sites aren’t available.

Where do Great Horned Owls prefer to nest?

You’ll spot these powerful raptors claiming elevated perches—from dense forest canopies and rocky outcrops to abandoned hawk platforms and even urban habitats—wherever nest site selection offers height, concealment, and hunting access.

Do owls nest in the same place every night?

During nesting season, you’ll notice owls show strong nest site fidelity, reliably returning to the same cavity or platform to incubate eggs and raise young, though nightly roosting behavior shifts as adults hunt and guard their owl territory.

When do great horned owls lay eggs?

You’ll see eggs laid from late January through February across most of North America, though southern pairs start as early as December—their nesting season runs ahead of spring’s arrival.

How long is the fledgling period?

The fledgling period for Great Horned Owls usually spans 6 to 8 weeks from hatching to nest departure.

Young owls develop flight feathers around week 6, taking their first short flights by week 7 with continued parental guidance.

What materials line the nest?

Great Horned Owls line their nests with bark fibers, feathers, animal fur, and plant fibers like leaves and moss—creating essential nest insulation that cushions eggs and regulates temperature during incubation.

How many eggs are typically in a clutch?

Most clutches hold two to three eggs, though you’ll occasionally spot a lone egg or four in resource-rich areas—proof that breeding cycle dynamics and nesting success rates hinge on prey availability and habitat quality.

What is the incubation period for eggs?

Incubation duration for owl nests usually spans 28 to 35 days, with parents maintaining egg temperature around 5 to 5°C and controlling nest humidity to support proper embryo development throughout the hatching process.

When do great horned owls lay their eggs?

You might assume spring, but these fierce raptors lay eggs from late January through March across most of North America—December in southern regions—defying winter’s chill to raise their young.

Conclusion

When those January snowstorms blow through and you’re tucked inside, remember: somewhere nearby, a female Great Horned Owl is incubating eggs on a frozen nest, trusting ancient timing over comfort.

Great horned owl nesting defies our expectations because these raptors play the long game—starting early means their owlets master flight precisely when spring floods the landscape with inexperienced prey. That calculated risk, repeated across countless generations, transforms winter’s harshness into their greatest competitive advantage.

- https://nestwatch.org/wp-content/themes/nestwatch/birdhouses/great-horned-owl.pdf

- https://www.birdnote.org/show/great-horned-owls-nest

- https://birdsoftheworld.org/

- https://www.nwf.org/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2020/Oct-Nov/Gardening/Owls

- https://ifnaturecouldtalk.com/when-to-trim-trees-and-protect-nesting-wildlife